On an August afternoon, a man climbs a road through the Échelle mountain pass. He is one of an increasing number of migrants who have chosen this route in the last year, especially as the pass through the Roya valley—in the Alpes-Maritimes—has become harder to cross. Dozens of migrants coming from Italy through the border city of Bardonnèche appear each day on the sinuous road that cuts through Névache, a municipality of 350 people.

“The number of crossings has significantly increased, especially in the past three or four weeks,” says Philippe Court, prefect of the Hautes-Alpes. “We expect 800 minors to be registered in 2017”—about 12 times as many applications for refugee status as the previous year, adds Jérôme Scholly, a regional public servant.

Faced with an unprecedented situation, residents of the Briançonnais region felt a spirit of solidarity. Associations believe that about 100 families are currently hosting migrants. “I started taking on one, then two, then three. And I ended up telling myself: why not the others?” says a resident of Névache, who insisted on remaining anonymous. “We find them outside, at night. We host them, feed them, and then they get back on the road.”

“The parish priest is very involved and called on the community to help migrants,” says Dominique Nioche, a church leader who agreed to dispatch lunches every day at the parish of Briançon. “As a Christian, I feel that we must help our neighbor,” she adds. Each day, some 120 meals are served by the parish to migrants staying in the neighboring village.

“There has always been a hospitable culture here,” says Michel Rousseau, treasurer of the association Tous migrants (All migrants). “This solidarity is just standard. However, [the police] make us feel like lawbreakers,” he adds.

Numerous residents have been questioned by authorities for assisting migrants, including a man from Névache who drove a pregnant woman and a few other migrants from the border in his truck. When people ask him how he’s doing, he answers bitterly, his face drawn: “I’m feeling like a criminal.”

Dominique Nioche admits that she was rebuked several times when organizing her lunches “from people who didn’t want to hear anything about migrants.” But she was also amazed by an unexpected show of solidarity from vacationers.

Madeleine, a retired woman who visits Névache every year, aided migrants she encountered on the side of the road on several occasions, driving them from the border to aid organizations. “I am proud of the Briançonnais region, where people are willing to take risks,” said Olivier Chrétien, the owner of a Névache inn, suddenly raising his voice in an attempt to hide his emotion.

According to the mayor, Jean-Louis Chevalier, “the population has, so far, shown some goodwill.” But “in the event of an incident, we can’t exclude the possibility that residents will turn against migrants,” he warns, wary of what could become should the situation persist.

The official measures in place are coming up short, although the prefect says that “in the department, every adult gets a response from the state.”

Given the magnitude of the migration flow, Briançon, with the help of city hall, opened a shelter that can host up to 16 people. “Last weekend, there were 90 people,” says volunteer worker Anne Chavanne. “Three weeks after its opening, the center was already saturated,” adds Luc Marchello, director of a youth social center in Briançon (MJC).

As a result, some migrants had to stay in the basement. It’s in that small 50-square-foot room with no windows that Modibo took up residence. He arrived six days ago, first through the Échelle pass, then Névache, and finally Briançon. “We left from the Bardonnèche train station at 6 p.m. and walked all night. When we arrived we had to sleep outside—we were so cold,” he remembers.

The tall, 24-year-old man alludes to his six month trip from Cote d’Ivoire shyly. When he talks of passing through Libya, he looks away. An embarrassed laugh interrupts his speech. He eventually says, “There were 37 of us piled up horizontally like dead bodies, covered with a sheet that prevented us from breathing.”

Here, Modibo shares a room with a few other young people, all from French-speaking Africa. The majority are minors, supposedly taken care of by the regional council. But according to Jérôme Scholly, the teams are overwhelmed. “Even with all that we are doing, the solutions found to host these minors are clearly insufficient.”

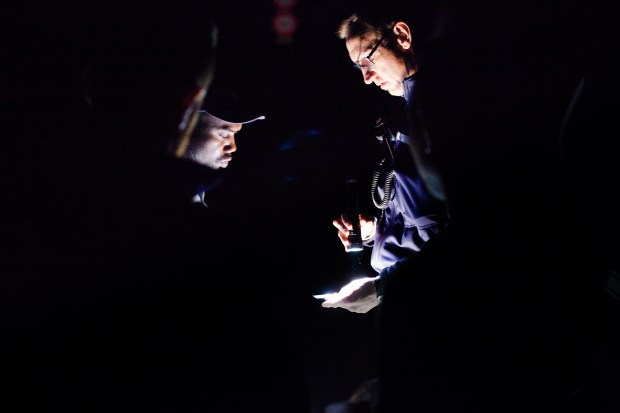

To stem the flow of migrants, police forces have increased operations. “The strengthening of identity checks at the borders stems from the fact that the pass through the snow-covered mountains becomes navigable during the summer,” the prefect explains. Many migrants are taken to the border, based on the Dublin agreements. A vast majority have already been processed in Italy and are sent back to file their asylum application.

But the multiplication of border checks “infuriates people, and the debate is heating up between residents and authorities,” warns Névache resident Bernard Liger.

In the town’s narrow streets, the story goes that it took one man over an hour to get his loaf of bread from the other side of the border, due to the traffic caused by numerous checks. Inn owner Olivier Chrétien also expressed some exasperation at the possible impact this will have on the town’s main industry—tourism.

Finally, the border checks are pushing migrants further up the mountains. About 10 days ago, two men were hurt as they tried to cross the border. “It looks like the two individuals fell as they were trying to run away from the police,” says Raphaël Balland, public prosecutor in the city of Gap. “One of them was seriously injured. An investigation is underway.”

“Some are now coming from the Vallon mountain pass, and they are forced to take severe risks,” says Bernard Liger. The 82 year-old veteran worries about the “circle of people moving around migrants”—smugglers—“who, in exchange for money, offer to take them to Marseille, Lyon, or Gap. He calls the situation “a dramatic regression.”

Originally published in La Croix on August 28, 2017. This article has been translated from French.