We crouch, hidden in the dense vegetation. We are in no man’s land, a strip of neutral territory between Bangladesh and Myanmar. A small stream ahead of us marks the start of Burmese territory. I am with a Bangladeshi border guard, a monitor from Human Rights Watch, and my fixer. Our breath is heavy in the thick, humid air. We hear a series of loud bangs, and then the smell of burning hits us. The guard swings his AK-47 onto his back, crouches to our level, points across the stream, and says, “Look. That’s where they are. … So close, again.” He is referring to the Burmese military

As people start to run toward us, we run in the other direction to find out what’s happening. A thick plume of smoke billows out from behind a patch of trees across the stream. A Rohingya man running toward us tells us the military nearby has just set fire to the houses a few hundred yards away. When I express surprise at how this could be happening so close to the border, the guard just shrugs his shoulders. It’s become a common occurrence, he tells me.

I spent three weeks documenting events along the Bangladesh-Myanmar border, where hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled into southern Bangladesh or become stranded in the 40-acre buffer zone between the two borders.

Since independence in 1948, successive Burmese governments have disputed the Rohingya’s historical ties to the land, claiming that they are Bengalis who migrated illegally when Burma was a British colony.

For decades the Rohingya, a mostly Muslim minority in Myanmar, have been effectively stateless in their ancestral land, formerly known as Arakan (what is now Rakhine state in western Myanmar). Some Rohingya trace their origins back to the eighth century, others to the 15th when thousands of Muslims came to what was then the Arakan Kingdom. Many more arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries, when Bengali laborers migrated to Arakan for work during British colonial rule. Because Britain administered the whole territory at the time, it was considered internal migration.

Since independence in 1948, successive Burmese governments have disputed the Rohingya’s historical ties to the land, claiming that they are Bengalis who migrated illegally when Burma was a British colony. In 1982, when the Burmese government issued a list of 135 recognized minorities, the Rohingya were not included, which effectively stripped them of their citizenship. Decades of discriminatory policies and repression have denied them human rights, education, and freedom of movement.

The current exodus began in August 2017, around when the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), an insurgent armed group operating in northern Rakhine state, attacked police and army posts, killing 12 officers. But according to a report by the U.N. human rights office, the Burmese military had started what the U.N. calls “clearance operations” on Rohingya villages even before the attack on police posts. According to reports by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International,the military’s crackdown has included burning down scores of houses, extrajudicial killing, and rape. Around 500,000 Rohingya have been displaced in what the U.N.’s human-rights chief describes as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

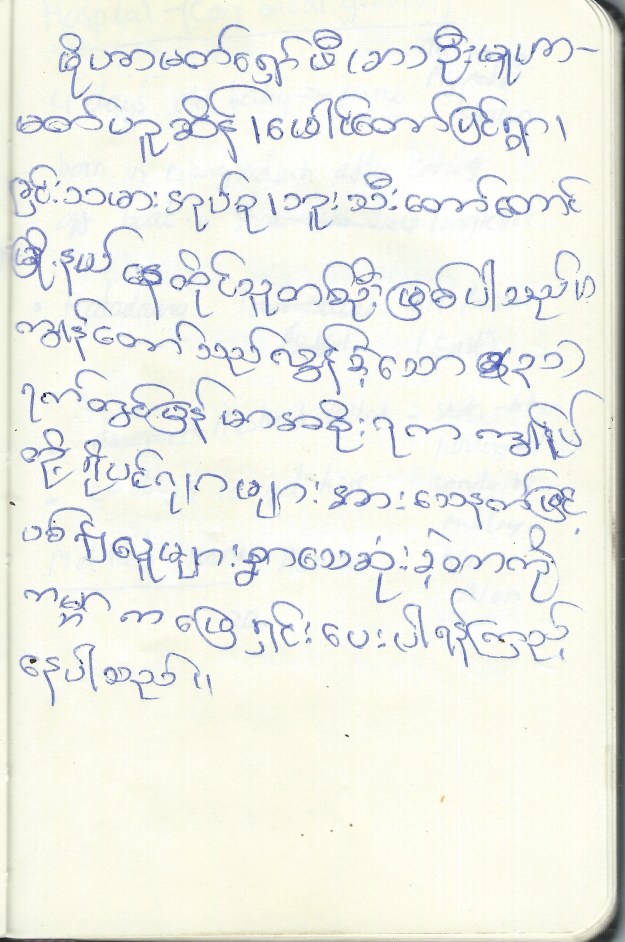

As I reported along the border, making my way through camps, along roadsides, hospitals, and paddy fields, I felt that the Rohingya’s own voices were lacking in my coverage. Aware of the importance of firsthand accounts—not just for accuracy, but also as potential evidence for future investigations—I started collecting testimonies from survivors: audio clips and handwritten letters from children, women, and men who had been displaced and suffered violence. Many of the horrific accounts correspond with details from interviews conducted by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. Reports of razed villages, indiscriminate shootings, rape, and mass graves appear again and again.

I asked the Rohingya I met what they wanted to say to the Burmese government or to the international community. This is what they said.

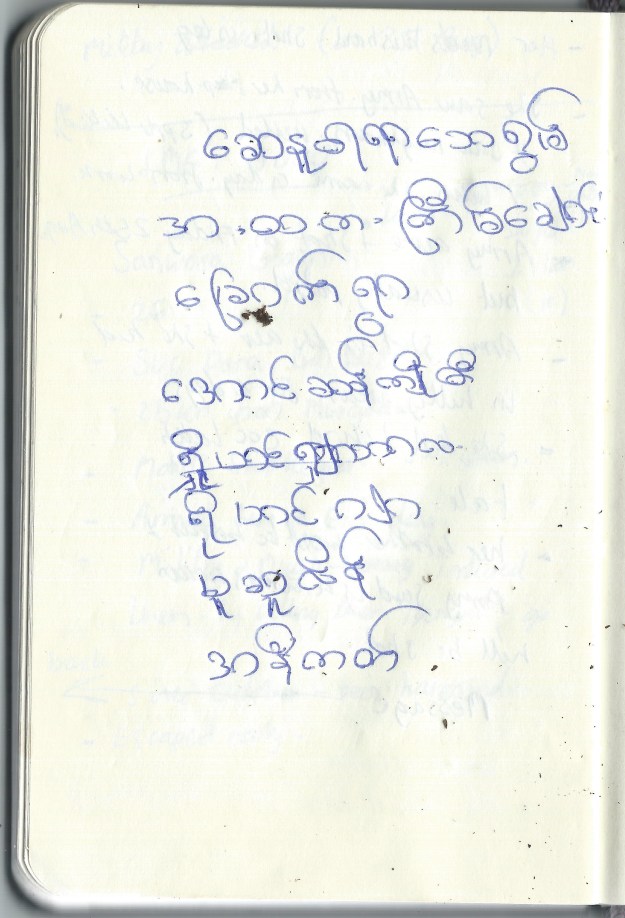

Name: Sanwara Begum, 26.

From: Boli Bazar, Myanmar.

Since October 2016 soldiers had harassed those living in Sanwara Begum’s village, setting up military outposts on the perimeter of their village and beating people in the markets. Once, when Sanwara Begum’s brother was shopping in the market a soldier who was patrolling told him that if he came again he would shoot him. They were often taunted by the soldiers as “Bengalis,” a derogatory implication that they weren’t Burmese nationals, but illegal workers from Bangladesh.

On Aug. 25, the military attacked. Sanwara Begum witnessed her niece’s husband get shot in the leg by the Burmese soldiers. She also saw three of her neighbors shot and stabbed by the Buddhist militia. She fled for the hills along with her husband and two boys, Mohammed Yusuf, 18 months (pictured), and Saiful Islam, 10. They trekked for four days through the thick jungle. She had no time to collect her money from her shopkeeping business, and left everything behind.

Translation of audio (by father): “The Burmese military and Buddhists burnt our house with mortar fire. The rockets fired into the house by the military burned her leg. I feel upset from living in unrest as they burnt everything we have, and I don’t even have the expenses to pay for our medical treatment. We don’t want anything except to return to our country. I just want the world to know that I want to go back home and that the Burmese government is responsible for burning down everything in our lives. I cannot even cry anymore as my eyes no longer have the tears to fill them now. We have lost our family members and I don’t know where many others are. My brother is also lost … they have destroyed everything—how will it be possible to go back? This is what I am concerned about now. We are suffering here [in Bangladesh] a lot … suffering from a lack of food and clean water. The hospital here is lacking equipment. The message I have is to tell the world I want to go back home [to Myanmar] and that I want the same for my fellow brothers and sisters.”

Name: Nur, 6.

From: Maungdaw District, Myanmar.

Nur has been hospitalized in the Cox’s Bazar General Hospital since October 2016, when the Burmese military last launched attacks on Rohingya villages. I visited her two days in a row and the second day she was less shy and became curious, letting me take her portrait. With her hand swollen from complications from her injury, she could not hold a pen to write. She let her father tell her account of what happened.

Name: Mohammed, 34

From: Rathedaung, Myanmar

Mohammed and his family fled from Rathedaung, Myanmar, after the Burmese army started burning homes and shops in their village. Their journey through dense jungle and muddy paddy fields took four days. They carried with them all their belongings and two babies, aged two and three. Mohammed and his family witnessed many of their neighbors shot by indiscriminate gunfire and estimate around 200 people in the village were killed, including Mohammed’s father, whose stomach was slashed open by the Buddhist militia. Before arriving at the Bangladesh border, the boat driver who offered them a lift demanded money from them. Having no money to offer, Mohammed paid with his wife’s necklace, earrings, and rings.

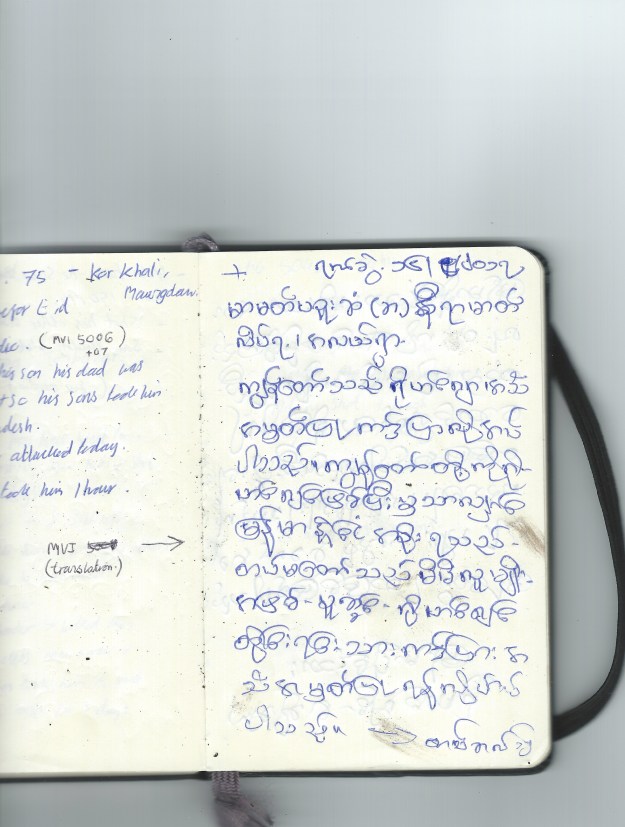

Name: Nur Mohammed, 75.

From: Kor Khali, Maungdaw, Myanmar.

Nur Mohammed worked as a fisherman in his village until it was attacked on Aug. 30. He ran toward the trees when he saw bullets flying over his head, but a helicopter flew directly over him. Grenades were thrown out of it, and one explosion tore into the sides of his legs. Still, he and his wife, who fractured one of her hands during the commotion, both managed to escape. But his daughter was injured during the attack and he does not where she is, or if she survived. The rest of his family is in Kutapalong refugee camp, a few miles away from the hospital he is in.

Name: Mohammed Shofi, 20.

From: Buthidaung, Myanmar.

Mohammed Shofi crossed the border into Bangladesh via the Tomuru border, where mines have injured and killed several refugees fleeing Myanmar. On the evening of Aug. 24, he heard gunshots and clashes with the Burmese military for about two hours. The next day the military arrived at his village and fired shots before before dousing petrol over houses. The soldiers and militiamen were armed with long knives and rifles (G3 and AK-47s). They rounded up a group of people from the village in a nearby field, separating the men from the women. The women were taken inside a large house, where they began screaming. Outside, the men were lined up and shot in the head. Those that survived the initial shootings were executed by the Buddhist militia. After, the house, which he estimates contained a few hundred women from the village, was shot into and then set on fire.

Later, about six army trucks arrived to take the bodies to a military outpost a mile away. Around 300 men from the village were captured. Another hundred escaped into the nearby jungle, and 200 died in the fields after being rounded up and shot or executed. Mohammed Shofi watched this as he hid paralyzed in fear amongst trees overlooking his village.

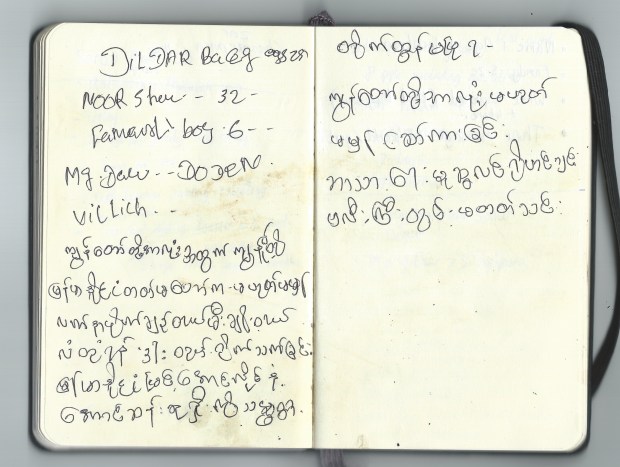

Translation of audio: “My name is Mohammed Yahya. We want our rights back. Aung Sung Suu Kyi and the Army chief Min Aung Hlaing have forced us to leave our country. We are not Bangladeshi like they say … we were born in Arakan. Our parents were also born in Arakan. We want to go back to our land. The military, police and other authority have the power to grant us our basic rights. We want to work and live in Rathedaung, Buthidaung and Maungdaw like ordinary citizens. We want to live in our way just like the other ethnic groups can do in Burma.”

Names: Mohammed Yahya, 22 and Mohammed Anas, 13.

From: Mirullha, Myanmar.

Mohammed Yahya left his village with his nephew, Mohammed Anas, 13, on Sept. 3. They both fled by boat following attacks on their village by the Burmese military and Buddhist militia, who torched their house and killed their livestock. Their boat, intended for fishing, was full of people. It was carrying 33 people, 10 of whom were young children, and left at night, as they felt it would be safest. Mohammed Yahya watched from the trees as he saw the Buddhist militia members slit the throats of elderly men and disabled people who had been tied up. The soldiers used AK-47s and had RPGs. The military also laid mines along the perimeter of the village. Mohammed Yahya saw his cousin, a fisherman, killed in front of him, struck by bullets in the paddy fields. He tells me that the Burmese military would call him “Bengali” and tell him to get out of Burma, and that members of ARSA are the only people who have supported the Rohingya. “They only stand up for [our] rights and are not terrorists like the government says in order to kick us out.”

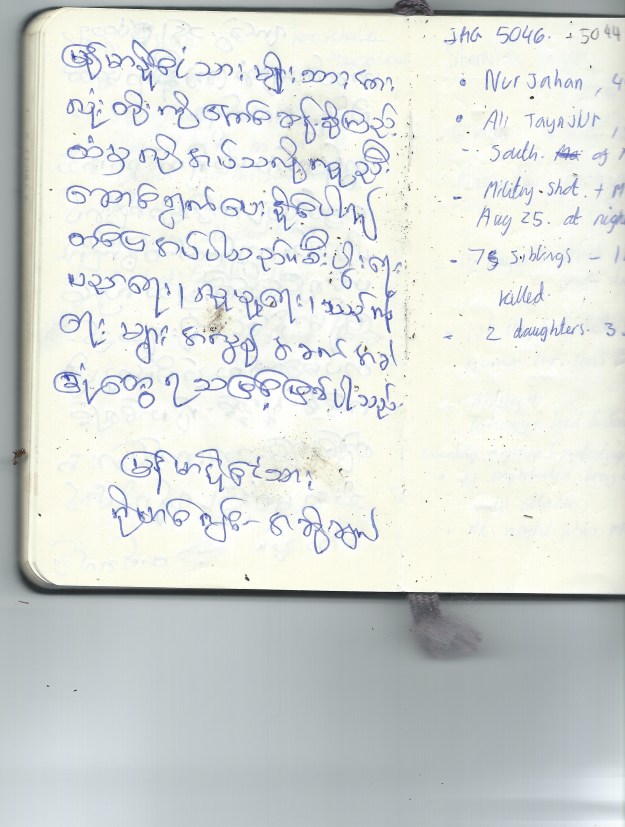

Name: Munwara Begum, 20.

From: Boli-Bazar, Myanmar.

On Aug. 24, the Burmese army and Buddhist militias came to Munwara Begum’s village. She saw bullets raining down throughout the night in the jungle outside her village. The next day she saw a helicopter dropping soldiers down by rope into the nearby fields. Her uncle was shot by one of the soldiers as they raided the houses next to hers. While they went through the houses across her street, she fled with her son and husband.

![“I never want to go back [to Burma]. Aung San Suu Kyi promised we would be safe the last time the violence broke out and she failed to stop it. I never want to go back.”](https://explorepartsunknown.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/comp-7.jpg?quality=95&strip=color&w=625&h=0)

![“I never want to go back [to Burma]. Aung San Suu Kyi promised we would be safe the last time the violence broke out and she failed to stop it. I never want to go back.”](https://explorepartsunknown.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/comp-7-letter-e1517416144889.jpg?quality=95&strip=color&w=625&h=0)

Name: Nesaru, 38

From: Gur Khali, Maungdaw, Burma.

Nesaru’s village was attacked on Sept. 1, on the day of Eid. She witnessed men from her village being sliced across the throat and legs by the Buddhist militias. Her nephew and son-in-law were killed during the attack. She used to take care of the animals on her farm before the atrocities and was forced to leave them all behind as she escaped to Bangladesh, where she stays in the Kutapalong refugee camp.

Translation of audio: “I don’t want to stay here in Bangladesh permanently without ever being able to return to my original home [in Myanmar]. We never had Burmese nationality rights because the government there did not recognize us. We still don’t have it after all these years. With all this violence how can we eat? How can we live? The military have burnt down and destroyed my house and vehicles. How can I go back to doing what I’ve always done? I want justice, yes. I want justice from the world.”

Name: Mohammed Sayed, aged 50.

From: Tomru village, Myanmar.

Mohammed Sayed’s house is burning behind him as I take his portrait. The blackish smoke can be seen billowing faintly behind his head in the shot, yet he insists on giving an interview. He worked as a driver just across the small stream behind him in his village.

Mohammed Sayed left his house on Aug. 30, fleeing the threat of Buddhist militias and the Tatmadaw (Burmese military). Hiding on a nearby hill, he watched the events unfold. “They [shot] brush fire [burst shots] and burnt the houses … they burnt three of my cars.” From what he saw, “the army shot two women and five men they had lined up in a field and took their bodies into the Burmese Border Guard camp.”Mohammed Sayed said there were around 40-50 soldiers. He lists the victims he knew; a 16-year-old girl; a 50-year-old man; a 42-year-old man.

On the Sept. 13 (the day this photo was taken), Mohammed Sayed had been living in the camp in “no man’s land,” the neutral area between Bangladesh and Burma. His son, who would return to their original house, checked the situation frequently. That day, as his son walked towards his house, he witnessed the Burmese military and Buddhist militia shooting at people with slingshots before dousing the cars and houses—including his—in petrol before lighting it up. He ran for his life through the trees. “I want justice,” he said.

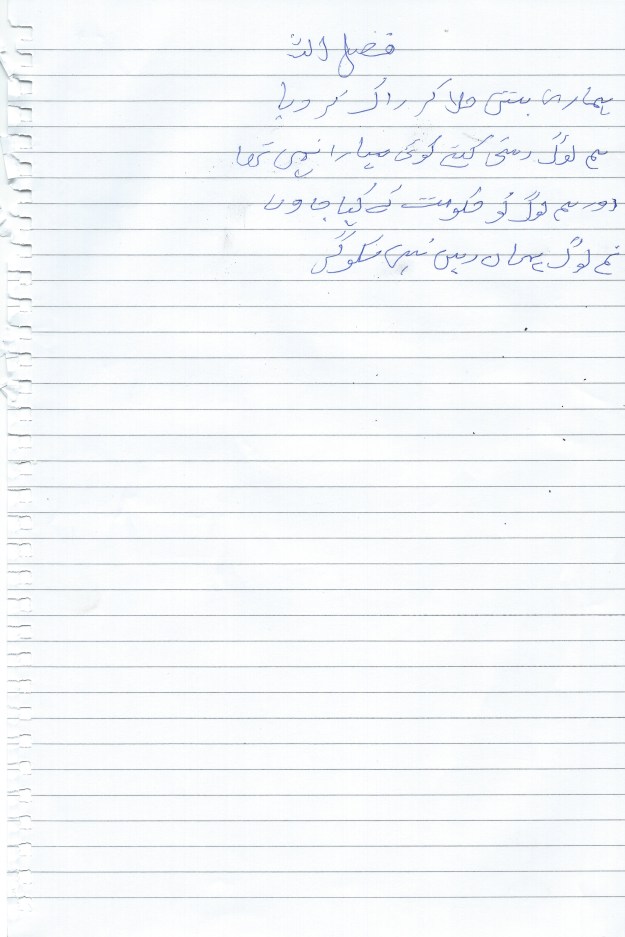

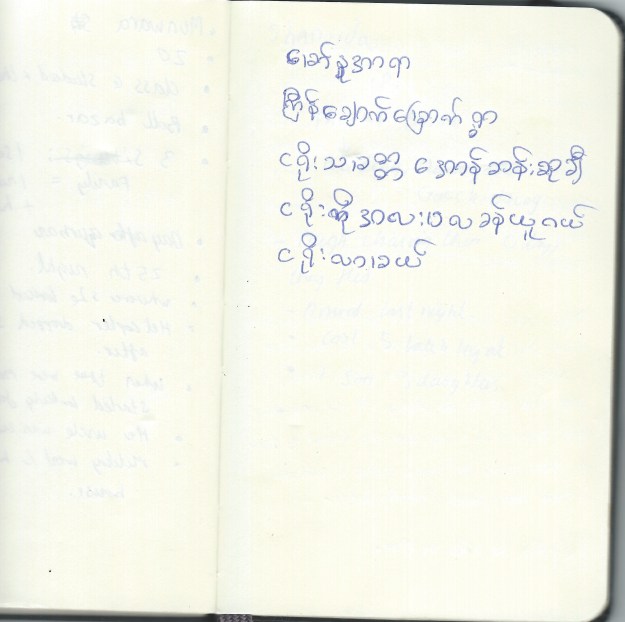

Name: Noor, 32.

From: Maungdaw District, Myanmar.

Noor has six-month-old twins. Her husband, Dildar, worked as a shopkeeper in their village in the Maungdaw District of Myanmar. Women in rural Rohingya villages often do not attend school, and Noor is unable to write, but her husband wrote her message for her.

“We are citizens of Burma. Aung Sung Suu Kyi can save our citizenships and keep us in our land but she gave power to the hands of the Army Chief Min Aung Hlaing, and in doing so gave him the power to kill us. When the military find us in the open, they shoot brush fire at us, old people, children, women, everyone gets hit by the bullets. They raped them. They raped the women. They burnt our villages to the ground. The villages are gone. We are Rohingya, our home is Arakan. We will only go back if they [the Burmese government] can accept us as Rohingya.”

Originally published on Roads & Kingdoms on Jan. 31, 2018.