Post-punk: That’s a thing. Post-rock: less of a thing but still a defensible genre. Post-grunge? The term is most often used to ridicule ’90s bands with a penchant for that certain Eddie Vedder–inspired vocal yarl—bands like Silverchair or Candlebox. It can also just mean, literally, after grunge. So the term essentially lumps together any band proliferating a specific style of snarling with any ol’ ’90s-sounding music released after 1992 or 1993, give or take. But if we were to embrace it as an elaboration on grunge, like we do post-punk? In the days, months, and years after grunge ceased to be the vibrant wellspring of blissed-out distortion it once was, Sub Pop, the label synonymous with grunge, continued introducing the world to a wealth of variations on the form.

Grunge is visible in the popular imagination in terms of fashion obsessed with ripped jeans and Kurt Cobain, but what about the music? Merriam-Webster defines it as “rock music incorporating elements of punk rock and heavy metal; also: the untidy fashions typical of fans of grunge.” Despite its utter lack of detail, this definition is in many ways completely appropriate. It was a concept of many forms with the most identifiable consensus among bands being a notable tolerance for noise. Ultimately, the context of grunge is what’s most telling. It’s the story of how so many loud musical experiments coalesced into something specific and yet so vague. Like the New York punk scene or San Francisco’s Summer of Love before it, grunge was the scene of Seattle in the latter half of the 1980s.

The ’80s was a vibrant and prolific time in pop music, but Seattle was often left off tour schedules by many big labels at the time, leaving garage bands to their own devices. The isolation mixed with a punk rock ethos, thanks in part to SoCal indie label SST Records, which brought bands like Black Flag and Minutemen to town—bands that celebrated their otherness. They were still calling them “new wavers.” The contrarian sentiment struck a chord with a subset of the Seattle population, and the unabashed slacker attitude and resultant brazen posturing settled in and became habitual. Soon Seattle had its own scene of bands, and they were exchanging their own takes on this loud, long-haired music of the ’80s, all the while assuming no one outside the city was watching. And for a time, no one was.

In a pre-internet world, Bruce Pavitt was among them. A wannabe rocker and enterprising individual, he created a fanzine for regional music and called it Subterranean Pop, later shortened to Sub Pop. Like the bands themselves, Pavitt was figuring it out as he went along, distributing mixtapes and eventually releasing original music by Seattle pioneers like Green River, Mudhoney, and Soundgarden. So when Pavitt joined forces with Jonathan Poneman and incorporated the business in 1988, they were already established as the volume-friendly indie label. Add to the mix the photography of Charles Peterson and the soon-to-be-household distressed type aesthetic of the Sub Pop brand, and you have grunge. They were the complete package of taste-making prowess, so when a little-known band from Aberdeen called Nirvana moved to town later in 1988, they signed a deal with Sub Pop. The band’s first single, “Love Buzz,” became the inaugural release of Sub Pop’s new mail-order subscription service, Sub Pop Singles Club, and the rest is history.

By the time Nirvana’s revolutionary album Nevermind appeared in 1991, the band—along with many others first introduced to the mainstream via Sub Pop—had moved on to bigger labels and cities while Sub Pop toiled to get beyond its reputation as “that grunge label.” Still, they carried on exploring tangents in popular music and working with recording artists interested in pushing the envelope, and their multifaceted approach continued to gestate and evolve at home—some strains darker and deeper still, others more refined and universally accessible.

The following chronological list of albums highlights some of the best of Sub Pop’s catalog with specific attention paid to the conceptual breadth of seminal post-grunge moments in music history. Sub Pop also worked with many great bands omitted here, including The Postal Service, the Shins, Iron & Wine, Beach House, and Wolf Parade, among others; but this roundup chronicles more specifically some of the bolder iterations of post-grunge concepts in pop experimentation and players directly associated with the movement’s originators and mythology. Consider it a list of high-water marks of Sub Pop at its post-grungiest.

1. Mark Lanegan, The Winding Sheet, 1990

Today Mark Lanegan is one of the great grunge-era survivors, drifting unrecognized through a critically acclaimed solo career (he’s also played in Queens of the Stone Age). Released before both Nirvana’s Nevermind and Pearl Jam’s Ten, Mark Lanegan’s The Winding Sheet fell squarely in the grunge era, but, contextually, it was half a generation wiser. At a time when pop music had become impulsive in its excesses of wealth and hair-sprayed indulgence, Lanegan, with his SST band, Screaming Trees, was busy creating psyched-out proto-grunge, stylistically more resonant with what was soon to be the Seattle sound. Few at the time could have imagined just how the coming wave of grungy music might capture the heart of a youth culture grown tired of Mötley Crüe videos, but with the release of The Winding Sheet, his first solo record, Lanegan’s delivery implies a more knowing vision. Much more interested in roots music than punk rock, the songs remain passionately bold in character but take the form of the prematurely jaded troubadour, gesturing toward the next chapter for himself and pop culture in general. The cover of Leadbelly’s “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” featuring Kurt Cobain and Krist Novoselic, didn’t hurt, either.

2. Sebadoh, Smash Your Head on the Punk Rock, 1992

Lou Barlow, bassist for the “godfathers of grunge” Dinosaur Jr., formed Sebadoh with Eric Gaffney. Barlow is known better for his vulnerability and almost sugary knack for pop sensibility, but this collection of songs—Sebadoh’s first with Sub Pop—is full of tongue-in-cheek grunge interpretations, emphasizing the lo-fi ideal commonly attached to subsequent indie contemporaries like Pavement. Sebadoh’s Smash Your Head on the Punk Rock may also be the label’s noisiest. Compiling songs from earlier releases, Rocking the Forest and Sebadoh vs. Helmet, Barlow’s transcendent pop moments hide amid the clang (see “Brand New Love” or “Pink Moon” for examples; and yes, that’s a Nick Drake cover), but overall this is a noisy affair indeed. This is Sebadoh at its most abrasive; posing less as rock antihero and more as classic grunge misfit, Sebadoh might just be the heart of oddball grunge.

3. Earth, Earth 2: Special Low Frequency Version, 1993

Embrace your love for the weird here—this is in fact as slow as music gets. And the weird part is not the actual chord progressions (they’re there if you can find them). It’s the willingness to go so deep into a void of what-if and obliterate the normal conception of what a rock song should be. The elements are there, but the compositions bank on the notion that the aesthetic of the lone sustained sonic drone is enough. This is amplifier worship at its purest, and some might even call it soothing.

4. Codeine, The White Birch, 1994

This is really an endorsement of any Codeine album via Sub Pop, but the band’s final release, The White Birch, is most sonically prescient. Similar to the aforementioned Earth, there’s a lot of slow, sustained sound here, but there’s a vocalist… and he sings kind of like Michael Stipe? If Earth conceptually tickles the brain but becomes unlistenable after two minutes, Codeine maintains respect for the vitality of a form. In fact, this album contains some of the best rock climaxes of the quiet/loud-verse/chorus trope often associated with successful post-grunge bands like Stone Temple Pilots and Weezer—only rendered here more cerebral and minimalistic. The White Birch is full of spots of spoken-word and droning heaviness that create negative contemplative space not usually associated with rock ’n’ roll until years later.

5. The Murder City Devils, In Name and Blood, 2000

The Murder City Devils created blues-based sloppy rock inspired by equal parts Kiss and Iggy Pop, with an eerie pseudo-goth organ for good measure. Perhaps due to the swaggering performance of Spencer Moody’s emo/punk anti-charisma, the Murder City Devils found themselves on tour playing similar gigs to more emotionally-indulgent bands. But I would argue that the anthemic In Name and Blood is more timeless than the sound of some of their more experimental emo contemporaries.

6. Sleater-Kinney, The Woods, 2005

Founding members Carrie Brownstein and Corin Tucker both played in prominent punk bands in Olympia (Excuse 17 and Heavens to Betsy, respectively) before forming Sleater-Kinney in 1994. Until No Cities to Love was eventually released in 2015, The Woods seemed to be both the band’s first Sub Pop release and its last album. Squarely of the ’90s, it for a time fit quite nicely in the more common notion of post-grunge but for the lack of frontman bravado. Yet Sleater-Kinney is arguably the central band to have emerged from the feminist riot grrrl movement associated with the Pacific Northwest. The distorted wall of sound on The Woods expertly balances cacophony with melody and even makes room for some of the band’s most playful tangents. This sounds far more like a band surging forward than fine-tuning the nuance of their swan song. It makes perfect sense The Woods would not be their last.

7. Kinski, Alpine Static, 2005

A large part of the success of grunge was the way it celebrated normal people rocking out free of preconceived notions on marketability. Kinski, truer than most to their Seattle locale, never stop rocking out. A mostly instrumental outfit, the band renders layered soundscapes that seem to progress in both directions forming one guitar-centric behemoth of an album just as psychedelic in its indulgent repetition as it is dynamic, with moments of groove-heavy hard rock. If they ever care to respect the confines of pop-song convention, they might just have a chance of becoming a household name; selfishly, I hope they never do.

8. Chad VanGaalen, Diaper Island, 2011

Chad VanGaalen seems to have taken the notion of “you can do anything” and run with it—and somehow it would seem he’s done it all from his own basement. The Calgary auteur self-produces his music, animates and directs videos, illustrates his own album covers, and has begun engineering records for other recording artists as well. Think of the music of Daniel Johnston (not only because he’s playing in his basement) but with fewer demons and an added depth of lush orchestration. The songs organically evolve from garage-rockin’ grooves into sinister guitar tangents and back through cinematic dirges saved by bursts of victorious indie jangle. This is the current indie-rock darling of the list for anyone growing weary of all the noise.

9. Shabazz Palaces, Black Up, 2011

Sub Pop is not even remotely known for hip-hop, but it’s also not surprising that Seattle’s Shabazz Palaces caught the label’s attention. Consisting of Tendai Maraire (son of Dumisani Maraire) and Ishmael “Butterfly” Butler (previously of Digable Planets), Sub Pop could not have found a more out-there group to chart its first foray into hip-hop. The duo released two prior EPs, which garnered much attention in Seattle and the hip-hop community in general, before revealing their respective identities outside of the Shabazz Palaces moniker alone. Their first release, Black Up, completely dismantles the sonic expectations of hip-hop—or any genre, for that matter. Drifting through a vast scope of instrumentation, the album is a thorough exploration of possibility, and it maintains constant contact with your pleasure centers despite its bold experimentation.

10. Daughn Gibson, Me Moan, 2013

Daughn Gibson sings like Unknown Hinson’s rebellious son who just realized rock ’n’ roll is more than a vaudevillian laugh. You might at first find his unnatural vocal manipulations overbearing, but the subtle dance groove and his rich natural baritone will coax you into this haunting album. Like the brooding romantic trucker cousin of Matthew Dear, there’s something so delightfully unexpected in this honky tonk mashup that hearing Glen Campbell’s “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” sampled on “Won’t You Climb” really comes as no surprise for a man choosing Don Gibson as his stage namesake.

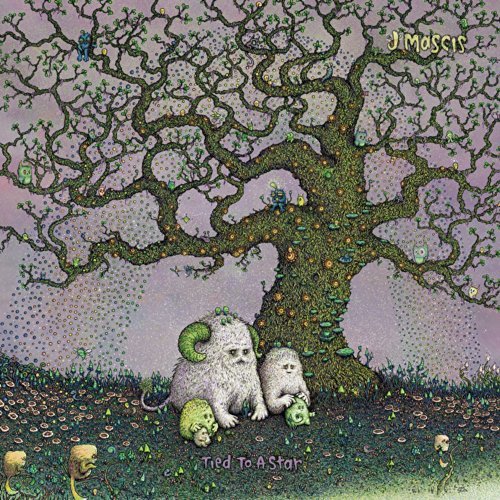

11. J Mascis, Tied to a Star, 2014

The commodification of popular music is an exercise in attempting to understand popular frustration and catharsis, distilling those feelings down to a bite-size product, and then selling the mess back to its source. And then there are people who, despite the endless pressure of market credibility, just keep doing whatever it is they’ve been doing—J Mascis is one of them. He’s often cited alongside his band, Dinosaur Jr., as one of the notable inspirations for grunge. Seeing that he’s from the northeast, he’s a significant rebuttal to the notion of grunge being a story of Seattle and a reminder of the genuine complexity often lost on genre specifications. I have no idea if he claims grunge in any way, and considering the aesthetic quality of his two Sub Pop records (this and the 2011 release, Several Shades of Why), one suspects he’s not too worried about it either. If you’re familiar with Dinosaur Jr.’s sound, you’re well acquainted with the technical prowess of J Mascis’s dexterity on the guitar; however, Tied to a Star sees him trading in his electric and writing heartfelt songs full of the same masterful craftsmanship, translated to an acoustic. There’s no one more fitting for the 11th notch on a scale preoccupied with loudness, yet here he is, confidently and somewhat quietly demonstrating his musical depth. What could be more post-grunge than compulsively delving into the self and coming out the other end refined, more mature, and downright pleasant-sounding?