There’s a whole range of things Sicily is known for worldwide. Food clearly is at the top of this list, as well as history, beautiful weather, gorgeous landscapes, and more recently, the European refugee crisis. I am a journalist from Palermo, Sicily’s capital, and whenever I travel overseas, I witness the happiness on people’s faces when they learn that I am from the home of cannoli, pizza, pasta, and beautiful Mediterranean women. Over the years, I have come to realize that I am lucky enough to live in one of those places in the world that people choose to visit on holiday. And they’re right to do so.

However, there’s another side to this island paradise. One that you can really see only if you live in Sicily for longer than a vacation. It’s a side you will know all too well if you grew up here. Of course, I’m talking about the Mafia. It is a phenomenon that we Sicilians are constantly asked about whenever we are abroad. “So you come from the birthplace of the Mafia?” “Does it still exist?” or “Might I get shot in the street if I visit Palermo on holiday?” (I was genuinely asked this question four years ago by an American friend.)

The answer to the first two questions is a big “yes,” but as to the third question: It is highly unlikely that you will be involved in a shooting while walking anywhere in Sicily. The days when the Mafia was rampant and its horrific acts were out there for everyone to see are mostly gone.

However, the Mafia, whose origins can be traced back to the 1800s, still exists. It has survived years-long wars with the state and against Italy’s anti-Mafia investigative committee. It has done so partly by becoming quieter and more hidden. Many people think that this growing elusiveness has made it harder to fight the criminal organization.

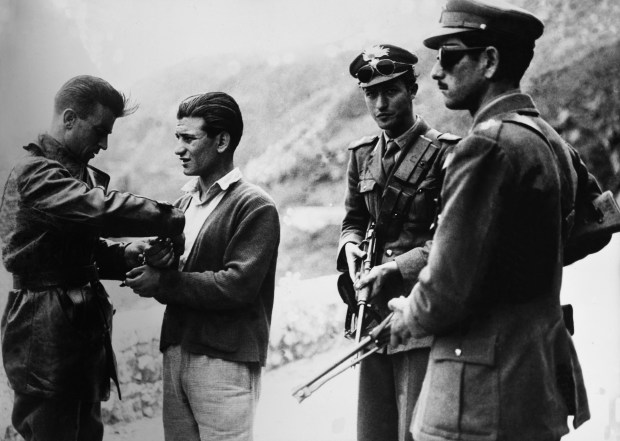

When Sicily began the transition from a feudal system to a capitalist one during the 19th century, collusion between criminals and politicians fueled by economic interests was rife. Ever since, there has been a lot of misunderstanding about the Mafia and its members—or Mafiosi, as they are known—both in Italy and abroad. Part of this misinterpretation stems from films and other media. These tend to portray the typical Mafioso as an uneducated, heinous, and rough farmer or businessman of some sort who has strict control over his social group, which in turn relies on the Mafia for help and protection.

Historically, this “Godfather”-like portrait of the Mafia is not entirely wrong, but things are very different today. One thing you need to understand about the Mafia is that its ability to survive and prosper is mainly linked to the fact that it knows how to adapt to social changes.

Sicilians like me live a dichotomy. We all know the Mafia exists: We feel it, and we see different forms of it in our daily lives. Yet it’s something so rooted in our upbringing and socialization that it can be very difficult to describe how we relate to it.

I was born in 1989, three years before the anti-Mafia judges Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino were brutally murdered. The Mafia killed them because their investigations started to uncover too much of the colossal pyramid that made up the Mafia’s workings. A lot of what they discovered came from the confessions of arrested Mafiosi. These incarcerated men understood that the only chance they had to reduce their sentences was to collaborate with the state.

Perhaps the best-known pentito (the term used to refer to a Mafioso who turned informer) is Tommaso Buscetta, aka Don Masino. It may come as a surprise, but before Buscetta revealed the secret details of the organization in 1984, our understanding of the Mafia was very limited. What was missing was a clear frame of how the Mafia was structured as an organization. A frame that went beyond the individual names of Mafiosi to the interrelations among them, the internal conflicts, the level of corruption of state officials who colluded with criminals, and the economic interests behind these illicit collaborations.

My mother tells me that she remembers all too well when the news of Falcone’s death (the first of the two judges to be assassinated) hit the headlines in May 1992. She was in Paris with my father and simply fell on the sofa and stared at the TV screen, she was completely incredulous. Two months later, Borsellino’s turn came. Like Falcone, he was killed in a bomb attack. Both of them had consciously started a private war against the Mafia knowing they could be assassinated at any moment.

The deadly attacks were ordered by a man who will be remembered as one of the most brutal bosses of the Cosa Nostra: Totò Riina. Over a criminal career that spanned 50 years, he acquired the nicknames “the Boss of the Bosses” and “the Beast.” During that time, he committed or ordered the murder of at least 60 people who belonged to rival Mafia families or worked for legal institutions.

If you visit Palermo, you can see evidence of his brutal legacy: On the highway from the airport to the city center, two commemorative obelisks sit on opposite sides of the road about halfway along the journey. They mark where Falcone, his wife, and bodyguards, were blown to pieces in May 1992.

I remember looking at those obelisks in September 2016. I was going to catch a plane to Padua to meet Giuseppe Riina Jr., the younger son of the man who ordered that assassination. I was interviewing him because he had just published his autobiography, which caused a massive outrage all over Italy. People were appalled that Riina Jr. portrayed his father in a positive light, and they regarded his book as an insult to the memory of the victims. For this reason, many bookshops refused to distribute it. In interviews conducted by investigators after Falcone’s death, we learned that the Mafiosi who assassinated Falcone were waiting on a mountain overlooking the highway. This location is not far from a town near Palermo called Cinisi. It is where another innocent man was killed by the Mafia before Falcone, Giuseppe “Peppino” Impastato.

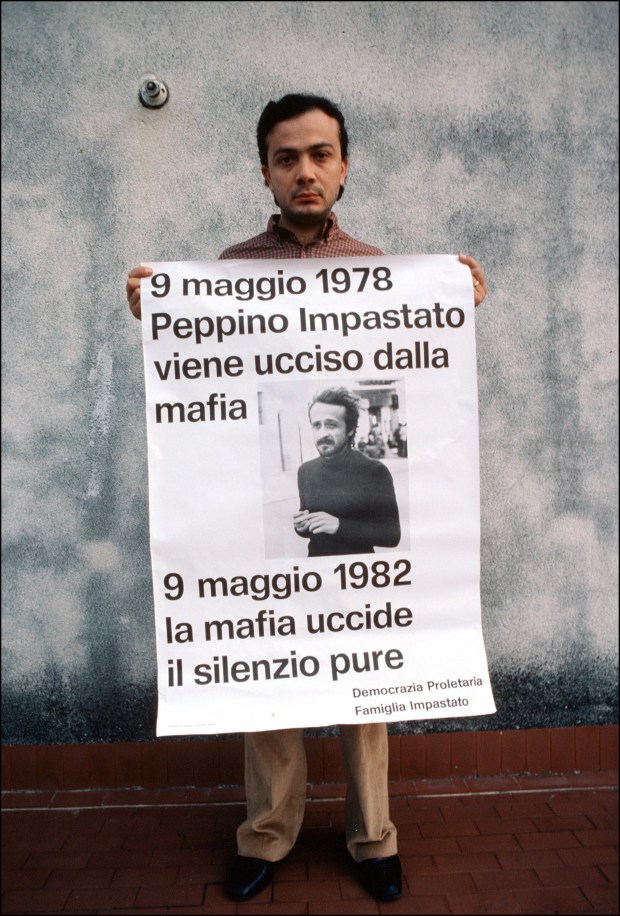

Like Riina Jr., Impastato was a son of the Mafia. His father, Luigi Impastato, was a member of a faction led by Gaetano Badalamenti. Unlike Riina Jr., though, the younger Impastato chose to fight the system. He did so by starting a satirical anti-Mafia radio campaign called Radio Aut, in which he named people and revealed their illicit business dealings—all of which put the Mafiosi in Cinisi under the spotlight. Ultimately, he paid the price of this battle when his body was torn apart by an explosion on May 9, 1978.

By coincidence, I find myself indirectly connected to this Mafia-related event. My grandparents had a summer house near Cinisi in the 1970s, it was just a three-minute drive from the business run by the Impastatos. My grandma remembers Peppino Impastato; you couldn’t miss his charisma or ignore what he was doing to fight the Mafia, she would tell me. In fact, she used to speak about him more frequently than my grandfather. Today, Impastato’s younger brother Giovanni Impastato continues to battle the Mafia. Together with his mother, Felicia Impastato, who died in 2004, he transformed his family house in Cinisi into an anti-Mafia association, Casa Memoria Peppino e Felicia Impastato.

I spent 15 summers at my grandparents’ house, and every time I went to the Impastatos’ to shop, I would notice a black and white photograph of a young bearded man hanging next to the counter. This is when I learned about the story of Peppino Impastato. More important, this is when I realized that something called the Mafia was real and very near me.

It’s difficult to summarize the history of the Sicilian Mafia. The number of victims is simply too great. However, one thing you should understand is that people like Impastato, Falcone, and Borsellino did not die because they were fighting the Mafia. They died because they were left alone to fight it. Who abandoned them? The institutions, their friends, their colleagues, their fellow citizens. People who were either too afraid or unwilling to join the right side. As an example, consider the fact that it took 24 years for the Italian government to condemn Badalamenti for Impastato’s murder, which meant his family members were able to find some semblance of peace only in 2002. Or that when his remains were found, the police recorded his death as a suicide.

History teaches us that isolation is all too often the ground upon which injustice can grow unchecked. Today’s Mafia is very different from the one of the years that preceded Falcone’s and Borsellino’s deaths. Back then, Sicily felt like a war zone because of the frequent attacks and murders. These days, the Mafia is rather small scale and goes mostly unnoticed. Crimes take the form of financial extortion of business owners, who are often blackmailed by Mafiosi and forced to pay them a percentage of their revenue to avoid having their businesses destroyed.

In contrast to the spectacular depiction of the Mafia that you might have seen in films and read in books, let me tell you that there is very little grandiosity surrounding the Mafia today. As a Sicilian, I like to believe that something can be learned from the shadows of our past and that the history of the Mafia is not a story of big heroes and enemies but rather of ordinary people with ordinary possibilities. As were those who sacrificed their lives to fight the Mafia and who will always be remembered.