A tent made of frozen cotton. A submarine built for a fish. Three pearly orbs, representing moons, floating in the sea below speedboats. A naked man planted headfirst in the snow with his legs pointing upward into the sky. A giant iceberg illuminated with a message: “Please Don’t Feed the Utopians.”

Yes, you read “iceberg” right, because I am at the first Antarctic Biennale, a pioneering art and science expedition in the seventh continent. More than 80 participants, including artists, a space architect, an Arctic explorer, and a sitar-playing neuroscientist, spent 12 days on a labyrinthine polar-research ship, the Akademik Sergey Vavilov.

Their goal was to channel the philosophy behind Antarctica’s status as a supranational territory, dedicated to science, into the creation of culture. The Antarctic Treaty of 1959 established the lofty value of peaceful cooperation, allowing any country to set up a base as long as it promises to preserve the wilderness and not upset the penguins.

“A main goal of this Biennale was to create platforms for the discussion of life in common territories—like Antarctica, space, and the oceans—so we can return to an ideological humanitarian dialogue about our planet,” said Alexander Ponomarev, the founder and commissioner of the biennale and the de facto expedition leader.

With his mop of gray hair, salt-and-pepper beard, and penchant for driving goggles, Ponomarev looks like a cross between a pirate and a steampunk zeppelin pilot. During regular mealtime speeches on the ship, he preaches about power and friendship with a heavy Russian accent, never forgetting to raise a glass or a defiant fist to motivate his motley crew.

In 2009 he turned up at the Venice Biennale—the art world’s premier event—in a multicolored submarine, one of many works that evoke his former life as a sailor. The 60-year-old will talk to anyone who will listen about his grand plan for an Antarctic contemporary-art museum partially submerged in the sea.

“Every time I come to Antarctica, it changes me,” Ponomarev said. “A man becomes more human. He gets a clear mind, interacts with nature, and suddenly begins to look at himself in a different way.”

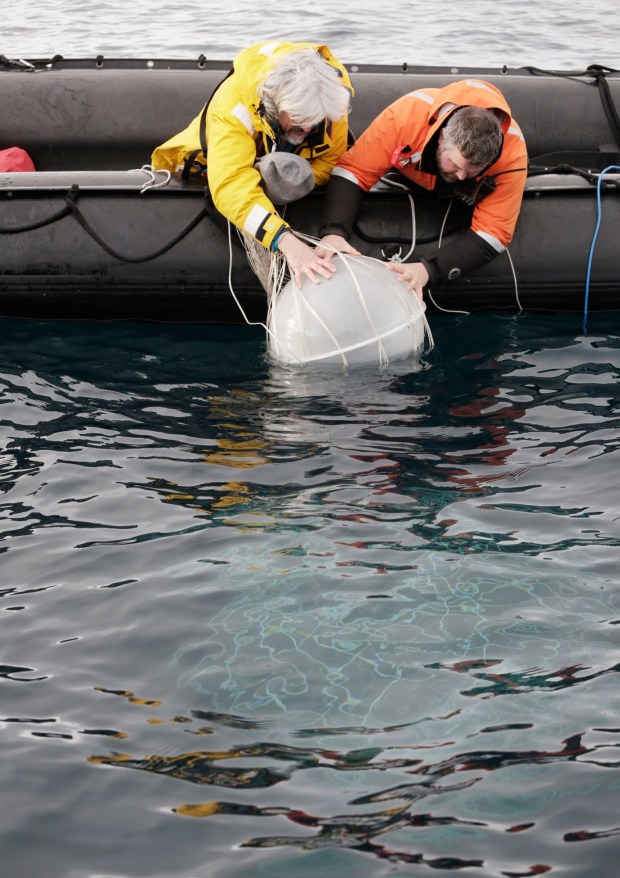

As well as selecting the roster of artists, Ponomarev produced an installation of his own, titled “Alchemy of Antarctic Albedo (or Washing of Pale Moons).” Three structures resembling upside-down hot air balloons were taken out to sea on speedboats. When they sank below the surface, the plastic globes lit up from within. The effect was a trio of mysterious waxing moons miraculously transplanted into the aquatic realm.

“The installation was about the destiny of the planet and the destiny of man,” Ponomarev explained. He also said he drew inspiration from drawings by Leonardo da Vinci and writings by Carl Jung. “We accumulate a huge amount of reflected complexes during our lifetime, which can lead to psychological states which cause depression, losing yourself as a personality, losing individuality,” he continued.

“In order to get rid of those complexes, you need to understand how reflected light works. I cleared the state of the moon, so the moon could be cleared of reflected light. Human creativity happens in a certain lunar state.”

Ponomarev’s piece adheres to strict rules about leaving no trace in Antarctica. All clothing, footwear, and equipment from the mainland was scrubbed and vacuumed before touching Antarctic terra firma.

The regulations also stipulate that nonscientific visitors must not bring alien flora and fauna to the region. One artist who probed the limits of that protocol was Paul Rosero Contreras. His installation, “Arriba!,” featured a cocoa plant from the jungle of his native Ecuador, housed in a temperature-controlled container to represent a tropical time capsule—taking us back 55 million years to when Antarctica itself had a temperate climate.

Contreras installed his piece in the middle of a breathtaking snowscape at Paradise Bay where fossils of tropical life have been discovered. He described the concept as a “time clash between past, present, and future” that explores how Antarctica allows you to “erase geography and rethink geopolitics.”

During lengthy negotiations with biosecurity authorities in Argentina and Ecuador, Contreras argued that his “plant is not a plant—it’s a sculpture with a cocoa plant inside.” He went on: “When I placed it on the site, I just started crying. I couldn’t stop for 30 or 40 minutes. Everybody told me it was impossible, but I believe art has to push you to the limit.”

The paradox of green leaves against a frozen backdrop of snow and mountains reflected a theme for many on the expedition. In Antarctica it’s difficult not to feel like an alien—dwarfed by its scale, you feel the landscape disrupt your sense of space and time. Urbanites and city dwellers in particular are left with very few crumbs of comfort or fragments of familiarity.

Spending time in such a pristine environment yet living on a ship that was producing considerable waste (even if that waste ultimately left Antarctica with us) and spewing carbon dioxide, we found it impossible not to wonder: Should humans even be here at all?

“Many people have said that being in Antarctica is intrusive, but to me that’s not true,” said Lisen Schultz, a Swedish sustainability scientist who attended the Biennale as an interdisciplinary participant.

“It’s important that we help humanity reconnect to our dependence on the biosphere,” she continued. “So maybe we need to come here in order to realize that. But it all rests on the assumption that everyone on this trip will bring something back—it cannot only stay with us as individuals.”

Works from the expedition are now on display in the Antarctic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, which opened on May 9, and will go on to tour international museums.

Joaquín Fargas, an artist and engineer from Argentina, is planning to incorporate the Biennale into his educational work. He created two “Glaciator” robots, which compress snow into ice to accelerate the formation of glaciers. It’s a poetically potent installation, designed to raise awareness about climate change in Antarctica, where the ozone layer is at its thinnest.

“We should think about how to use the knowledge and technology we have accumulated to improve the situation,” Fargas said.

He admitted that an army of “Glaciators” would be required to actually create a new glacier, but he was unconcerned by the difficulty of measuring the outcomes of his Antarctic experiment. “The message is that even if we don’t know the results, we need to do something,” Fargas explained. “Because if we do nothing, we already know what the result will be.”