It’s a fair bet that come summer 2017, the eyes of the food world—always ready for the next, the new, and the notable—will be fixed on Copenhagen, where chef René Redzepi will be opening the new iteration of his famed and influential restaurant Noma. (The original closed in February 2017.) Here, Redzepi talks with Roads & Kingdoms’ co-founder Matt Goulding about Noma 2.0, three-season cuisine, and why he’s “addicted” to doing pop-ups.

Some people think it’s crazy that we’ve closed Noma. It was successful, influential, and provided jobs for a lot of people—everything you could ever want out of a restaurant. We could continue another five to eight years and it would still be as full, and do well, but I also believe we’ve hit a high at the restaurant, and that’s a sign that we have squeezed what we can out of this space, and that it’s time to move on. We’ve been doing this stuff here for almost 14 years, and for the past three years we’ve been planning this move. I’m ready, I want to go to work and feel like it’s a new job; I can’t wait, honestly, I just can’t wait. In order to not fall down completely and become a potential caricature of what you set out to be, then I think you just have to kill it all and say okay, how do we start again, how do we keep staying on the edge?

Noma 2.0 is right in one of the most historic areas of Copenhagen, actually built on top of the old fortification of Copenhagen; we’ll be building quite a bit out there—seven new buildings. We are still a restaurant, but we are building it in this way so that it’s a flexible space—you know, what do we want to do in 10 years with Noma? Who knows, but we don’t want to create a place that can only be one thing. I don’t want to be in a situation where you are fixed in how you can use the space.

This is because we’re still playing around with what all of this means. I think that there’s something going on in our region that has been going on for awhile, but it’s been manifesting itself in these years where you could say that our region has come to enjoy a sort of mainstream acceptance from the foodie crowd around the world. We are all enjoying a bigger mainstream success, chefs are more confident, the Copenhagen dining scene is more confident. And I think that the ethos or whatever it is, I think it’s something that belongs to the region as a whole where we all contribute, and the sum of all of us makes it very powerful.

When we opened, we could win people over just by people being in the north. It was so exotic, to go on this journey and to sit at wooden tables and have a dagger in your hand and so on—it made everything taste better because of this new tactile feeling. But we need to keep exploring, to keep building these stories. We need to better understand what the hell does it mean to actually be a cook in the north. This very word the north, what does it even mean? North of what? Are you a local or not a local? People consider us to be a local restaurant but the menu right now has ingredients that come from a 1000 kilometers away which is nothing local. The reality is that Denmark has more in common with Germany than with Finland or Norway, especially when it comes to food.

The idea has always been that, as a fine-dining restaurant, you need to have a big menu, and finish this big menu off with a slice of meat, and then in between, you would have seafood, or more animal protein. But the essence of it, at least to me was always kind of the same—long format menus with meat at the end, regardless of the season. You had to satisfy the tyranny of that fine-dining menu structure. In the case of Noma 2.0, it will be very specialized: three different seasons, and there will be a period of microseasons within each of them.

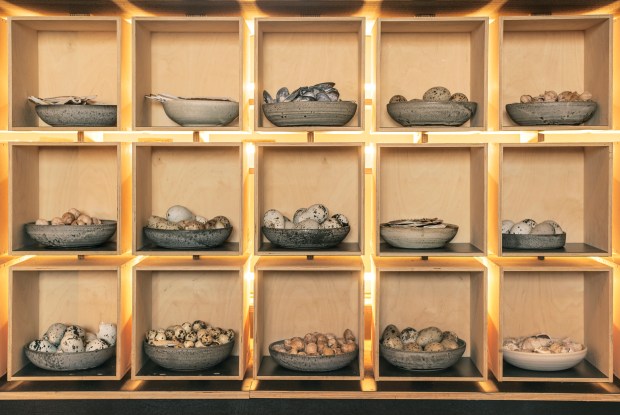

To understand our region is to understand that in the very cold months, there is a period where nothing really grows, and you’re dependent on your larder and you’re dependent on whatever else you have in root cellars, so you always struggle with that, trying to constantly figure out how to fill this menu that needs these very set things. But then you realize that if you look into the ocean, that’s actually when the season is best. We do cook a little bit of seafood and we have three or four seaweeds on the menu now but you can hardly call us specialists of the ocean. And it made so much sense to have a seafood focal point; when the season is right the oceans are ice-cold. Most flat and round fish—the bellies are full of roe and the livers are the best that they can be. And we haven’t even begun to talk about the interesting array of crustaceans in these waters.

The next shift we thought of was during the green season where we have so much to choose from, it’s just never ending and it’s always like a nuisance—you can have 100 ingredients from one day to another. And then it just made so much sense: When all of the vegetables and the plants and the flowers and the roots are there, why isn’t that what we’re serving?

From then on it was, “what happens then when everything stops being green, when the leaves start falling to the ground?” So we looked toward the forest to the game birds, the game animals, which is also something that we’ve been exploring in the past four or five years in its proper season. It’s so much more interesting to eat and to cook with all of these wild animals and it feels so much better to have these birds come in, plucking them ourselves and roasting them. When I grew up as a cook, it was simply—cook a piece of meat or a piece of duck and cut off the corners and the tips so it would be perfectly square. Once you pluck a duck and see it in its full beauty, you would never ever want to do that. It’s just a different way to approach ingredients, it has a flavor that to me completely surpasses the domestic equivalent; to me, it’s like comparing farmed lobster and wild lobster or farmed turbot and wild turbot.

So you have these three different focus points, and there’s a reason for our guests to come back three times a year as opposed to once a year, or maybe every second year because you display your seasonal kind of innovations and the format more or less stays the same all year round. As a cook, I’m excited again to be specializing, and I am also excited that we can offer something three times a year that is distinct and unique. Through this specialization and this point of innovation, I know that really amazing things can happen when you allow yourself to focus on something. So that’s where we’re going.

A big part of our pop-ups in Japan and Australia and now Mexico have been working with plants because we wanted to see if we could do something new; I mean the thought of us moving to this new place and falling into the trap of past successes because they worked—that’s depressing. So the pop-ups have been a perfect training camp. I’m not anymore, but I was nervous about how to make all these vegetables be as satisfying and delicious as, say, the seafood season or the game season where those types of ingredients just hit a more satisfying note for like 99 percent of all people. So, they’re a great way to experiment, but it also happens that we’ve become addicted to them—at least, I have. They’re not easy to organize; the Mexico one has been the most difficult by far, for many many reasons both political and logistic. But they have been some of the biggest experiences of my professional life and also my private life: traveling with my kids and seeing them go into a public school in Australia and an international school in Japan. In some ways, it’s like an elaborate team-building exercise, which sure beats walking over hot coals on a Sunday afternoon. So we’re not going to stop doing them.

I think you can’t just settle in and say great, a brand is created, and now let’s do business. There is something going on, an energy or a feeling that you could say is a Noma feeling, or a Scandinavian energy or feeling, and we want to build on that. Ferran [Adria, chef and owner of Spain’s El Bulli] was just here the other day and we had a long chat. I’ve been studying the case of Ferran and the case of many other very successful cooks and seeing what happens in the trajectory of our career span. We all have very different stories, but I want to try to build a story where I can be on the edge and be very creative, preferably until the day that I don’t want to work anymore.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.