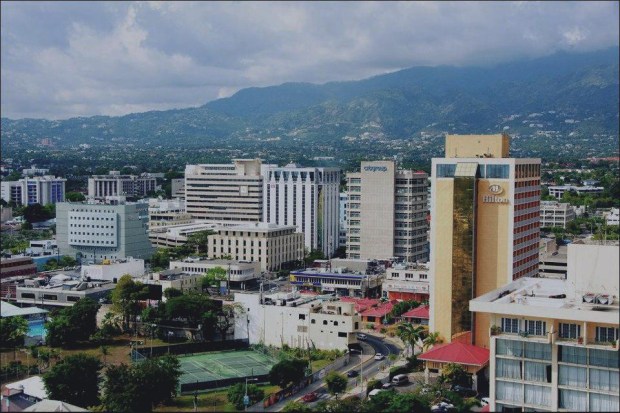

Attend any outdoor sound system party in Kingston and you are guaranteed to experience at least two things: loud, bass-thumping reggae and dancehall blasting from a gigantic stack of speakers, and clouds of marijuana smoke rising over the crowd. Like peanuts at a baseball game, the two go hand-in-hand, and it’s been that way for almost five decades.

While not everyone at the party is smoking, marijuana is usually easy to come by if you’re looking. Just stop one of the vendors who will be periodically walking through the crowd with 12-inch stalks, selling buds from the dried plant for $100 Jamaican dollars ($1).

An estimated 37,000 acres of marijuana grow across the island of Jamaica, but perhaps surprisingly to Bob Marley-worshipping foreigners, selling and using marijuana here has been against the law for the past 67 years. Until very recently, being caught with any amount of marijuana could lead to arrest and up to five years of jail time and a hefty fine up to J$15,000 (roughly $1,500). Those with marijuana convictions can also have a hard time finding work or obtaining visas to travel abroad. The strict illegality of cannabis in a country where the plant grows wild has long been a controversial sore spot between the Jamaican government, the Constabulary Force (the island’s police organization), and many of the country’s citizens—particularly Rastafarians.

But now, Jamaica’s government, which has long had a fraught relationship with the ganja-smoking Rastas, is slowly embracing the plant’s use. An amendment to Jamaica’s Dangerous Drugs Act, which was passed Feb. 6, 2015, Marley’s birthday, makes any possession under 2 ounces only a ticketed offense and allows any Rastafarian person to grow marijuana on designated lands. The amendment also permits the use of ganja for religious, medical, and scientific purposes. Smoking ganja is still prohibited in public places.

Rastafarians have welcomed the amendment, albeit with deep-rooted wariness.

“Give thanks for the decriminalization of herbs because we Rasta man go through a lot of struggle over it,” says Ras Ayatollah, sitting in the garden of the well-hidden restaurant of Ibo Spice on Orange Street in downtown Kingston that serves up a strictly vegetarian menu that Rastas called “ital.” A Rastafarian elder at the Scotts Pass Nyabinghi Center in Clarendon, about a 40-minute drive outside of Kingston, Ayatollah grew up a fisherman in the Kingston shanty community of Hannah Town. According to Ayatollah, he got his name after hearing a radio report that the Iranian Ayatollah had declared he would stop “wickedness and earthquakes.”

Marijuana first arrived in Jamaica with indentured workers from India (who called the plant “ganja,” the Bengali word for hemp and a term still widely used across the island) in the 19th century. The use of cannabis grew in popularity along with the rise of the radical, Afro-centric spiritual movement Rastafarianism in the 1930s. The movement, which originates in Jamaica, has roots in Abrahamic religious tradition but identifies former Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie as a Jesus-like figure who represented God on Earth.

Followers see Zion (often identified as Ethiopia) as a promised land they’ve been forcefully taken away from by Babylon—which encompasses what they see as a wide-breadth of corrupt Anglo-Western values such materialism and greed. Cannabis, which Rastafarians often refer to as “herb,” is a holy plant to believers, according to their interpretation of certain passages in the Old Testament. Many Rastas believe the plant grew on the grave of King Solomon.

The use of ganja was further promoted with the worldwide popularity of reggae in the 1970s. Many of its biggest stars—most notably Marley—adhered to tenants of the Rastafarian lifestyle and often sang about its sacred status along with the plant’s medicinal benefits. Peter Tosh’s anthem “Legalize It,” which was banned from airplay in Jamaica upon its 1975 release, is perhaps the most known example.

The hardline approach that the Jamaican government has taken toward ganja use and cultivation has naturally resulted in a long and strained relationship with Rastafarians. But the complexities run deeper than just ganja use. Like many elder Rastafarians, Ayatollah has endured decades of stigmatization by many Jamaicans and, in particular, the local police. Over the years, this has often played out in violence and aggravation.

One often-cited clash is the Coral Gardens incident, which took place in 1963. A number of Rastafarians took to the local police station near Montego Bay to protest police harassment over their presence near resort hotels. The situation turned violent, and eight Rastafarians were killed. The incident is still remembered each year on its anniversary by Rastafarians, who refer to it as “Bad Friday.”

Another famous incident in post-independence Jamaica revolves around the destruction of a downtown Rastafarian community that was called Back O’Wall in 1965. The area was a center for pan-Africanism and early Rastafarians; Marley lived here when he was young. After being branded by politicians as a slum and a center for violence, it was leveled by bulldozers and rifle-armed police officers. The area was replaced by low-income housing and renamed Tivoli Gardens, but it remained a hotspot for violence, epitomized by the government’s armed capture of Tivoli Gardens’ famed drug lord Christopher Coke in 2010, which resulted in more than 50 deaths, many of whom were unarmed residents.

These instances are among the reasons why Ayatollah remains skeptical about the government’s motives. But he’s hopeful that the Rastafarian community will see the benefits.

“At the end of the day, they should donate something to the Rastafari community in Jamaica for the struggles we endure,” Ayatollah says. “I know that in due season they will have to give back something to I and I.” (Many Rastafarians don’t say “me” or “I” but “I and I” in reference to their God, Jah, and themselves”—a mix of the Jamaican patois and the Rastafarians own spiritual use of language.)

Michael Barnett, a senior lecturer at the University of the West Indies and editor of Rastafari in the New Millennium, a collection of essays that examine the religion as a modern, worldwide movement, shares Ayatollah’s sentiments.

“The real issue that many of us in the Rastafari community have is if we are going to have a stake in the commercial industry,” Barnett says. “The commercial motivation by the government is quit obvious. But what regard is being paid to Rastafari? Shouldn’t Rastafari be a part of any economic benefits that are to be incurred in this initiative?”

To be sure, there is money to be made from legal ganja. The new law opens the door for the creation of licenses for allowing the development of a medicinal and commercial ganja industry—something toward which the powerful and business-savvy Marley estate has already taken steps, creating its own strain of the plant called “Marley Natural” this past November.

The new law can only benefit tourism, Jamaica’s biggest revenue-generator. More than 2 million people visited Jamaica last year, many in search of sun, music, and marijuana in resort towns such as Negril. It’s also here where rogue “ganja tours” are already attractions that authorities have largely turned a blind eye to, despite their illegality, possibly in fear of scaring away visitors.

“The investment opportunities from legalizing ganja are huge,” argued Delano Seiveright, director of the lobby group Cannabis Commercial and Medicinal Research Taskforce, at last year’s Investments and Capital Markets Conference in Jamaica. “The more obvious relate to the impact on our agriculture, tourism, and financial sectors.”

Upon passing the reform, Justice Minister Mark Golding echoed these sentiments, saying, “We need to position ourselves to take advantage of the significant economic opportunities offered by this emerging industry.”

Barnett doesn’t see why Rastafarians can’t also take advantage of these benefits.

“Rastafari should be able to make a living out of something they’ve long promoted and championed,” explains Barnett. “What may happen, and I hope it doesn’t, is that Rastafari will have no real part, or real input, in the commercial aspect of the herb industry.”

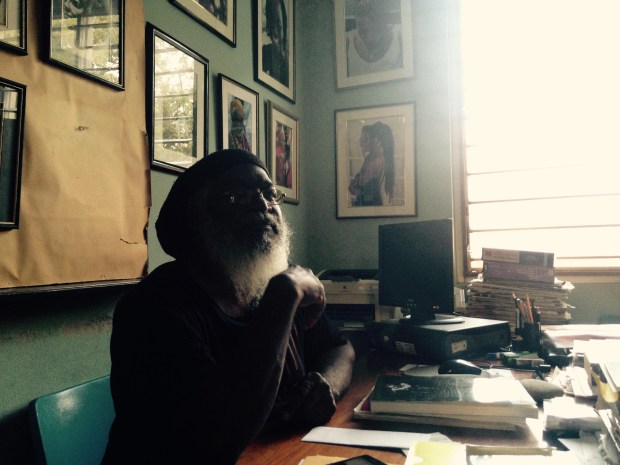

Barnett’s colleague Clinton Hutton, a lecturer in political philosophy and culture at University of the West Indies, has similar concerns. Speaking in his office surrounded by portraits he’s taken over the years of Jamaica’s Rastafarians, Hutton is pragmatic.

“I don’t think that we Rastas can say, ‘We have done all of these things, and therefore there’s automatic right.’ For me, they should have that right. But some rest of society and especially certain people in business, they will box that idea right out of our mouths, as we say in Jamaica,” he said.

Groups such as the Ganja Law Reform Coalition, the Ganja Future Growers and Producers Association, and the Cannabis Commercial and Medicinal Research Taskforce have been the driving forces over the past few years in pushing for ganja reform on the island. However, none of these groups has seriously taken up the issue of financial reparations or inclusion for Rastafarians. The various branches of the Rastafarian communities have also been slow to act. Having historically avoided political involvement, no significant political or social group has developed from the various branches of their community.

But how the new law will financially benefit Rastafarians is not the only concern.

While the new law does recognize Rastafarians use of the plant in holy ceremonies and makes steps to allow these practices to go unprosecuted, this brings up another question that has existential consequences to Barnett: “There is something problematic in allowing the government to now determine who is Rasta,” he said. “It’s a whole can of worms in itself.”

How exactly this will play out legally is still to be seen. The Jamaican government has determined that the Cannabis Licensing Authority will be the regulatory body helping establish the lawful industry. However, National Security Minister Peter Bunting has acknowledged in a speech to Parliament that the law would take some time to implement.

Hutton calls the government making decisions on who is Rastafarian foolish. “Maybe everyone will become Rasta now,” he says with a laugh.

Yet, it’s these kinds of unanswered issues that Hutton believes make it all the more imperative for Rastafarians to be active and vocal about the implementation of the law.

“This is an issue that Rastas have died for,” Hutton explains with a sudden seriousness. “This is an issue many have gone to prison for, that they have been victimized for, that they have been shut out of school and jobs for. Everything should be done to understand that. This issue is one of rights and justice. Not just in Jamaica but globally.”

Originally published on Roads & Kingdoms on March 20, 2015.