Earlier this year Kenya’s highest court heard a case that would potentially decriminalize homosexuality. Current law holds that “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” is a felony, punishable by up to 14 years in prison. The court is expected to announce its decision on September 20.

Explore Parts Unknown’s Tafi Mukunyadzi spoke to Kawira Mwirichia, a visual artist and LGBTQ activist, about her work and hopes for the future.

Tafi Mukunyadzi: What are some of the obstacles that LGBTQ Kenyans face today?

Kawira Mwirichia: Queer people are mostly under pressure to keep who [we] are and what [we] do private. Some people are “OK” with you being gay, as long as it’s not in their face. I feel like that’s the major sentiment.

There aren’t really any protections for transgender people because the government doesn’t recognize them. When you’re in the process of transitioning, you will draw attention from the world, so that opens them up to discrimination.

Kenya is quite conservative, mostly because of religion, but also because of some cultural beliefs. It’s interesting because, I think, the religious and cultural perspectives on the issue actually sort of clash when you dig deeper. What people perceive as cultural—what is traditionally African—is actually rooted in religions introduced through colonialism.

Mukunyadzi: Are you referring to Kenya’s sodomy law, introduced by British colonists?

Mwirichia: Yeah, Christianity is seen as very African, but it’s not. If you look back at who we were culturally before we were colonized, we were so diverse in terms of sexual practices and our gender expressions. The erasure of who we were before colonialism has really affected how we live our lives as Kenyans and as Africans in general.

Mukunyadzi: If homosexuality is decriminalized, how do you think that decision would be received throughout the rest of Africa?

Mwirichia: If the law is struck down and we really own that change as a country, it might be positively received throughout Africa. It really depends on how well we embrace it.

Mukunyadzi: In your conversation with Anthony Bourdain, you mentioned the possibility of a violent backlash. Is that something you think could happen?

Mwirichia: There’s definitely that fear, because, I think, calls to push back against that decision could be interpreted as calls for violence. So the fear is very legitimate.

Mukunyadzi: What kind of campaigning strategies is the queer community in Kenya using to change people’s attitudes about homosexuality?

Mwirichia: There are several organizations working to decriminalize homosexuality in Kenya. Personally, I’m more focused on the community itself and building ourselves up internally. A lot of the conversations that I have about creating awareness of the queer community’s rights always focus on getting society to accept us. My work focuses on getting us, as a community, to a place where we are proud of ourselves and are full of self-love. Being in that place would allow us to live in an open way. And that would affect society around us because it would be easier for other people to relate to us. It might change your neighbor or your friend or the village where you come from if they see you living your life happily and openly. They might realize that queer people are not just these fictional things they think the West made up.

Mukunyadzi: How do you get LGBTQ Kenyans to a place where they feel free to live more openly?

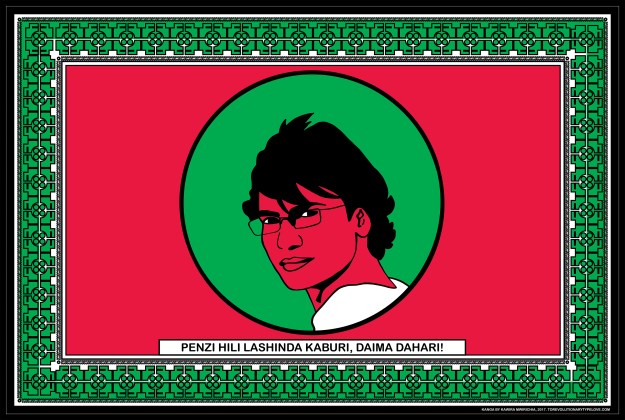

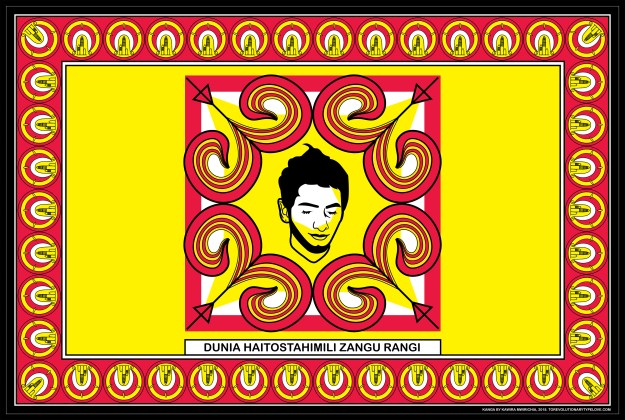

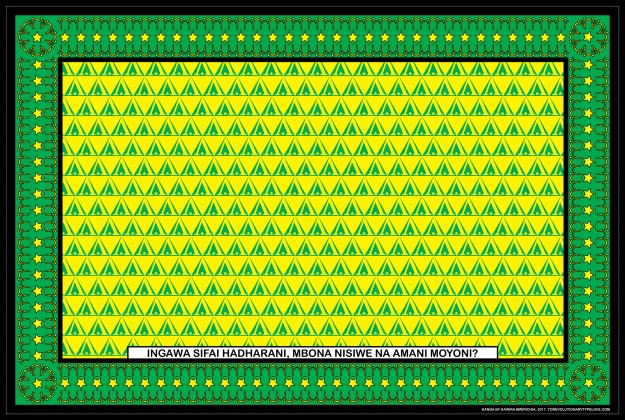

Mwirichia: I’ve started a project called To Revolutionary Type Love that celebrates the queer community through a traditional cotton cloth that we call a kanga. I was inspired to start the project after attending a friend’s wedding. According to my friend’s cultural background, the groom’s family went to the bride’s home to pick her up and take her to her new home. They led her out of the home and placed kangas on the ground for her to walk over as they were singing and welcoming her to her new family.

Mukunyadzi: Placing the kangas on the ground is a gesture of goodwill?

Mwirichia: Yes, and it hit me that this gesture wouldn’t be experienced by queer people in Kenya because of homophobia. The fact that straight people get to have their love celebrated so openly and so freely by their family, and yet we have to hide who we are really moved me.

I thought we could celebrate ourselves by creating our own kangas with our stories written on them and lay them out for ourselves. I want to create a kanga to represent every country in the world, and I take suggestions for the designs and text that go on the kangas.

Mukunyadzi: How many kangas have you created so far, and which one is your favorite?

Mwirichia: 34. I have a bunch of favorites.

Mukunyadzi: What does the kanga for Kenya say?

Mwirichia: It says, “My love is valid.” That line was inspired by Kenyan actress Lupita Nyong’o, who talked about dreams being valid when she won her Oscar. So it’s a play on that, and it was a response to President Uhuru Kenyatta. When President Barack Obama visited Kenya, our president was pressed about LGBTQ rights and he dismissed the topic as a nonissue. So the kanga sort of addresses that as well.

I feel like society is becoming much more open, at least in interactions I’ve had. I’m not scared. I don’t think it will be bad, but I am cautious.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.