Sirte was still an obscure settlement when Moammar Gadhafi was born in a goatskin tent on its outskirts in the summer of 1942. There was a fortress of sorts and some shacks on the white sandy shores of the Mediterranean inhabited by people who lived off its waters. What is now Libya was then Tripolitania and, so far that century, had been occupied by the Ottomans, the Italians, and then the British.

After Gadhafi rose to power in a 1969 coup, this village of fishermen became Libya’s other capital, built up by the self-professed “King of Kings” as a monument to himself. It had broad avenues, grand villas, pristine white housing estates, and tree-filled parks. Tripoli remained the legal seat of government, but there were ministries in Sirte too, as well as conference centers and a university—outsize buildings for a population of only about 70,000. In 1999 he proposed the creation of a United States of Africa, with hist his hometown as the administrative center. But plans never materialized.

Sirte came to define Gadhafi’s bizarre and tyrannical rule—and later the humiliating agony of his death. When the uprising began in 2011, he stayed in Tripoli for as long as he could, fleeing only in August, just before rebels—aided by NATO jets and special forces units—took the city.

His wife, his daughter, and two of his sons made for Algeria, another son to Niger. But Gadhafi retreated 270 miles east along the coast to Sirte, one of his few remaining strongholds.

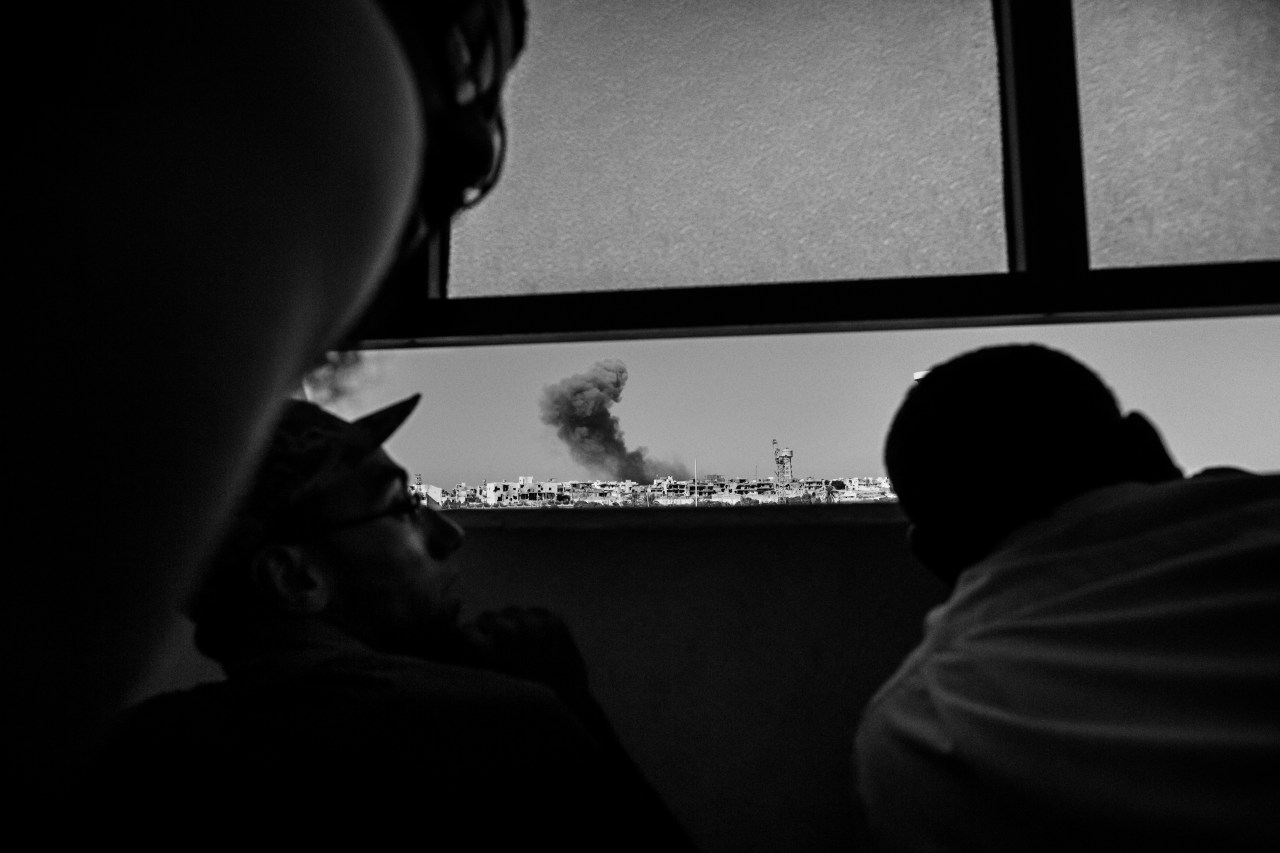

The opposition fighters were mostly from Misrata, irregulars with Kalashnikovs and pieces of uniforms looted from government stores, their artillery mounted on pickups. They besieged the city for weeks, unaware their former ruler was hiding there and wondering why the loyalists fought so hard.

Moammar Gadhafi’s fourth son, Mutassim Gadhafi, organized the defense, stationing snipers and mortar teams and launching costly counterattacks and nighttime raids that made only momentary gains. Thousands of civilians fled, and those who stayed hid in basements, with little food, water, or medicine.

In the early hours of Oct. 20, Mutassim Gadhafi’s troops, cornered by the rebels, formed a convoy bound for the village where Moammar Gadhafi was born.

Soon after, NATO aircraft spotted some 75 speeding armed vehicles near the city’s western edge. A U.S. Predator drone fired, hitting one of the cars and splitting up the convoy. The group containing Moammar Gadhafi turned south and was hit again, by French aircraft; 10 of the vehicles were destroyed. Gadhafi and his personal guard escaped on foot. The rebels tracked them to a graffiti-covered storm drain in a culvert strewn with rubbish.

Gadhafi’s final minutes are captured in erratic cellphone footage shot by the men who found him: He is wounded, his face bloodied and horrified, being jostled and pulled into the back of a pickup full of shouting fighters. He is begging for his life, a pistol in his face. He is unconscious in the dirt, stripped of his tunic. Then he is dead in the back of an ambulance, ugly red holes in his head and stomach. In the walk-in freezer of a Misrata meat store, his corpse lies on a plastic-covered mattress while people line up to take pictures.

When Sirte’s residents returned in the days and weeks after Gadhafi’s death, they found their homes, schools, and hospitals had been destroyed in pursuit of a man whom many of them mourned. Libya’s new transition government promised to rebuild, but it was politically difficult to prioritize a place so strongly identified with Gadhafi when the cities that rose up against him were badly damaged too.

The people of Sirte remained neglected and often resentful, under control of opposition militias including the Salafist Ansar al-Sharia. They were spared much of the post-revolution upheaval for a time, though, and were able to begin putting their lives back together, even without much outside help.

Then ISIS arrived. It was 2015, and the militant group wanted to establish another base in the Middle East after losing ground in Iraq and Syria. Libya, by then split between warring administrations in Tripoli and Tobruk and awash in oil and weapons, was vulnerable. Some Ansar al-Sharia fighters there split off and pledged allegiance to the so-called caliphate, and some Gadhafi loyalists were seemingly happy to facilitate a group opposed to the rebels.

Some 1,500 fighters ended up in Sirte. Libyans joined Tunisians, Iraqis, Syrians, and Nigerians, among others. ISIS’s prominent Bahraini cleric Turki al-Binali was a regular presence there. The group took control of the main government buildings and made its headquarters next to the conference center that Gadhafi built for pan-African summits.

There were new and draconian rules then. Women had to wear thick, black shapeless clothing and hide their faces; men could not shave; boys and girls were segregated in the classroom.

Transgressors—those who stole, drank alcohol, smoked in cafés, contacted outsiders—were punished, along with anyone accused of connections with police and outside militias. Lashings, amputations, and beheadings were carried out in the central square. Bodies were hung from billboards at a roundabout not far from where Gadhafi was killed.

Residents—the ones who could—fled again, leaving behind others with nowhere else to go or without the means to escape.

And there was soon fighting. Misratans, some of whom were involved in the 2011 battle, attempted to retake the town. And again the clashes were fierce. The Libyan militias pushed into the city, house by recently rebuilt house, with help of U.S. airpower and their own aged but still destructive artillery.

ISIS fighters used the same snipers, mortars, and nighttime attacks as Gadhafi’s men, combined with their own suicide car bombs and improvised explosive devices. As they gradually lost ground, the jihadists left rubble filled with booby traps, corpses, and unexploded ordnance.

It was over by December 2016. Surviving ISIS members made for the desert. And the city, twice flattened, was left with an even smaller chance of being rebuilt. Elsewhere in Libya, things were worse still. Three rival governments were now competing for power, and what was left of the economy was in steep decline. Sirte was again alone.