The sting of tear gas dissipated long ago. There are no more gunshots. There is neither fire nor bomb, riot nor rumor. It is not 1962. This morning the campus is quiet, save for the soft pat of rain, the echoing clap of tree branches. Leaves wisp to and away from each other. A car idles along the perimeter of the Circle, the hub of academic and administrative life at the University of Mississippi.

At the crest of the Circle sits the Lyceum. Built in 1848, with towering white columns and deep forest green shutters, it is the oldest and most recognizable building on campus. It is also the most fissured. University anthropologists tell of the enslaved black folks who helped build and maintain its antebellum allure.

In front of the Lyceum, the American flag sags and flaps heavily. Beneath it, a chasm. Campus police have removed the state flag, a decision that came after a three-month student-led movement that both extended and disrupted an institutional history of racial conflict, violence, exclusion, and activism.

The flag was removed on October 26, 2015. Two years later I am in Oxford, Mississippi, meeting with Tysianna Marino and Dominique Scott at a restaurant on the downtown square. Both recent graduates of the university, Marino, who goes by Ty, and Scott—Dom—were, by all accounts, the foremost visionaries and catalysts of the campaign’s call for the removal of the flag.

“I remember walking around pushing a book cart,” Marino says, her voice barely registering above the rising mutter of coeds, clinking glasses, and rap music. “I was on one of the morning shifts at the library. … I saw the email that they had removed the flag, and I just dropped to my knees. I just took a moment. I couldn’t believe it.”

“I was at home,” Scott says matter-of-factly. “I cried. And it was more of a cry of, like,” she breathes in deeply and exhales. “Relief. I was glad I [didn’t] have to do that anymore. Like, yeah, I can’t believe that we did that … but also, like, I am so glad that I don’t have to do this anymore. So I cried.”

Scott arrived at the university from Dallas, Marino by way of Pascagoula, a town on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. They were both highly visible and active across campus during their freshmen and sophomore years. In the summer of 2015, though, as they anticipated the start of their junior year, they were reimagining what that visibility, as black women with nuanced and developing perspectives on race and social justice, might actually mean, especially in a place like Oxford.

By August of that year, they had both assumed leadership positions in the campus chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), with a vision as simple as it was ambitious.

“When we started, it wasn’t just about the flag. It was about removing all of the Confederate iconography across campus—” Marino remembers, pausing for effect. “At one time.”

“We wanted it all. We wanted it all,” Scott smiles defiantly, confidently.

Their goals placed them in well-charted territory. Since the early 1990s, university students, leadership, and alumni have raged and debated over the presence of Confederate imagery throughout the campus’s social, commemorative, and built landscape. In 1997 talk centered on the visibility of the Confederate flag at athletic events, especially among the fans at Vaught-Hemingway Stadium during football games. Ultimately, then Chancellor Robert Khayat instituted a ban on “pointed objects” (i.e., flag sticks) and limited the size of all flags and signs allowed into the stadium. In 2003 it was the university’s Colonel Reb mascot, which was eventually replaced by the Rebel Black Bear. In 2014 it centered on the school’s nickname, “Ole Miss.” Administrators ultimately dispensed with any formal endorsement of the moniker, limiting its use to the school’s sports teams. The following year it was the marching band’s rendition of “Dixie,” which the band is no longer permitted to play in any arrangement. Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs Brandi Hephner LeBanc gives voice to the university’s ongoing commitment to addressing concerns related to the presence of Confederate iconography on the campus, noting that “conversations and efforts are, of course, ongoing.”

Today a 30-foot Confederate monument, erected in May 1906, stands at the eastern tip of the Circle, almost squarely at the center of campus. (In October, 2016 the university gave the monument a new plaque imploring visitors to view the statue as both a memorial to the dead and a reminder that the defeat of the Confederacy meant freedom for millions.) One can still hear cries of “the South will rise again” from the bellies of drunken tailgaters on football Saturdays; and until recently a handful of academic and administrative buildings bore the names of past state and university leaders who were ardent opponents of the Civil Rights Movement or otherwise expressed racist sentiments: Johnson, Lamar, Vardaman.

Until that rainy Monday morning in October 2015, the Mississippi state flag would have been counted among that number, another symbol evoking a history that the university wanted to forget, or at least recast. The current version of the flag, adopted by the state in 1894, features a Confederate emblem: a red canton overlaid with a blue saltire dotted with 13 equidistant white stars. There had been two state banners before it, one unofficial and one official: respectively, the Blue Bonnet Flag of 1861 and the Magnolia Flag from 1861 to 1865. While the current version of the flag has flown over the state since 1894, it did not become a fixture in the social, cultural, and political landscape of the state and region until the 1940s, when some southern politicians adopted the flag as a campaign emblem—oftentimes an emblem that emboldened anti-Civil Rights Movement sentiments.

“We wanted it all,” Scott repeats herself, this time dragging out each syllable.

Both Marino and Scott place the origins and impetus of the campaign in the summer of 2015. They watched in horror as the news reported death after death of unarmed black Americans during encounters with the police or while in custody: Walter Scott and Freddie Gray in April, Sandra Bland in July. They turned away in disbelief when they learned that Dylann Roof had murdered nine parishioners in the hallowed space of the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Marino and Scott describe that summer as a moment of reckoning, as impossibly devastating and exhausting, and ultimately as the tipping point that compelled them to take action.

“It infuriated me that Dylann Roof had been glorifying these symbols,” explains Marino. “And [students on this campus] wore them proudly, flashed them … revered them. And not that those symbols were responsible, but the same people that glorified those symbols were responsible for the deaths of people that look like me or that look like my grandma.”

“I had known I wanted to do something [about racial injustice] on this campus since freshmen year, and we had marched after the noose was hung on the Meredith statue, but after that summer it was, ‘I guess we really ’bouta do something.’”

They did something.

“I suggested that we start with a forum just because I think dialogue is important,” Marino recalls. “Then Dom was like, ‘I think we need to escalate after that.’ Then she proposed the rally and then the march.” Scott had just begun serving as a regional organizer for United Students Against Sweatshops, a student-led labor-solidarity organization. In the preceding months she had participated in Organizing Beyond Barriers, an internship program facilitated by the labor union Unite Here.

“We modeled our list of demands after the 10-point program by the Black Panthers,” Scott notes. After taking several days to strategize and refine their approach, Marino and Scott, along with a growing group of interested students, hand-delivered a letter outlining their demands to university leadership. They delivered the letter twice more before the campaign saw its first major victory, at the end of September: a meeting with university’s Division of Student Affairs

Both Marino and Scott describe this and other early meetings as “productive,” and say the Vice Chancellor was “direct”, “supportive,” and “gave reasonable advice.”

“The biggest thing that happened during the meeting,” explains Scott, “was that we were able to realize that some of our demands were simply out of the university’s control…Like, they couldn’t place a ban on what people wore or brought to The Grove on a given Saturday in September.”

“I wanted to be prescriptive and directive, to help them understand what we could and simply couldn’t do on the university’s side,” Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs Brandi Lebanc notes, echoing Scott’s sentiments. “What I remember trying to impress upon them was how important their voice was, but also that this would have to be a community decision.”

“After the meeting,” Marino recalls, “we decided to prioritize the flag as a part of our overall strategy.”

As meetings continued, Scott and Marino continued to refine the campaign. They would host a forum, then an on-campus rally, then a march through the Grove, a multi-acre sprawl of trees and open green space through the center of campus.

“The forum was a way for us to have a conversation on Confederate iconography on campus. The flyer literally was just a Confederate flag,” explains Marino. The provocative promotion paid off. The forum took place on September 29, attracted some 150 people—students, campus faculty and staff, and residents from across north Mississippi—and lasted nearly three hours. The next day the student senate began drafting a resolution urging the administration to remove the Mississippi state flag from all university-affiliated campuses.

The success of the forum and the subsequent introduction of the senate resolution demonstrated that the campaign was gaining traction, both on campus and in the greater Oxford-Lafayette community. Local and national media coverage of the campaign expanded, and, after initially rebuffing invitations to help kickstart the campaign, several other student organizations took notice and expressed support.

With this growing campus and local support, Marino and Scott moved forward with their plan for a rally. The aim of the rally was twofold: to bring visibility to the campaign and to continue applying pressure to both the student government and campus administration. It attracted some 200 attendees.

Yet the campaign’s momentum and mounting success also attracted impassioned dissenters. Among the rally’s attendees were about a dozen vocal representatives of the League of the South and the Ku Klux Klan.

“I’m walking from class to the rally, and I was so—” Scott loses her words. “I was crying.” She pauses again. “As I’m walking, I was crying. I was so scared. I was so scared.”

“I was terrified,” Marino interjects softly, then more forcefully. “I was terrified.”

Both women had already been dealing with on- and off-campus harassment and threats of physical violence. They describe feeling that the rally raised the stakes. Marino recalls being followed home by three white men in a pickup truck.

“I could see that there were two older men. I wasn’t sure who they were,” Marino says. “Then there was a younger guy who I remembered from the rally.”

Scott recounts the harrowing details of a physical attack in which a group of white men in a pickup truck approached her in the parking lot of her apartment complex, screaming racist taunts—“Go back home to Africa!,” “You are going to die, nigger bitch!”—and pelting her with newspapers that carried a cover story on her.

Marino shared her experience with only her closest friends. Scott, however, relayed the details of her attack to university officials on the day it occurred.

“[The administrators] who I told really rallied for me,” she says, explaining how the director of housing offered her temporary campus housing. At the suggestion of the University Police Department, Scott filed a police report with the local authorities, though she recalls that “nothing ever came of it.”

Both Scott and Marino also received support from the state’s NAACP chapter, who arranged for them to have an FBI escort at selected meetings and events until the campaign was over.

Despite ongoing threats—and propelled by a strong support system—Marino and Scott persisted.

“We were still planning the march. We were planning the march,” Scott asserts firmly, as if to remind any lingering dissenters, as if to put the universe on notice.

There was no march. Within two weeks of the rally, there were senate votes at the student, faculty, staff, and graduate-school levels. Each body voted in support of the resolution, with some dissenters and abstainers. Though Scott and Marino knew the outcome of the votes, they were still uncertain about the university’s timeline for implementation. That uncertainty lingered until the flag actually came down, on the morning of October 26, under the cover of rain, before much of the campus had begun to stir.

On the heels of the campaign, Marino, Scott, and other involved students were lauded for masterfully navigating very difficult terrain. In early 2016, they attended the 47th NAACP Image Awards where they accepted the “Chairman’s Award” on behalf of the University’s NAACP chapter.

Lebanc recalls of Marino’s and Scott’s work, “In that moment, we were incredibly blown away. They made us incredibly proud…telling the fuller story of what many people just didn’t fully understand.”

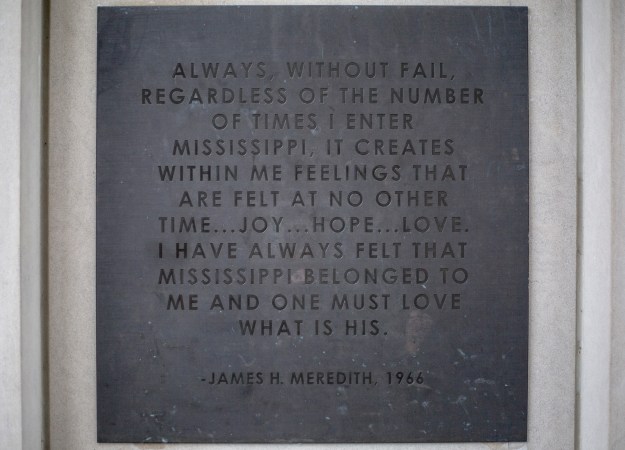

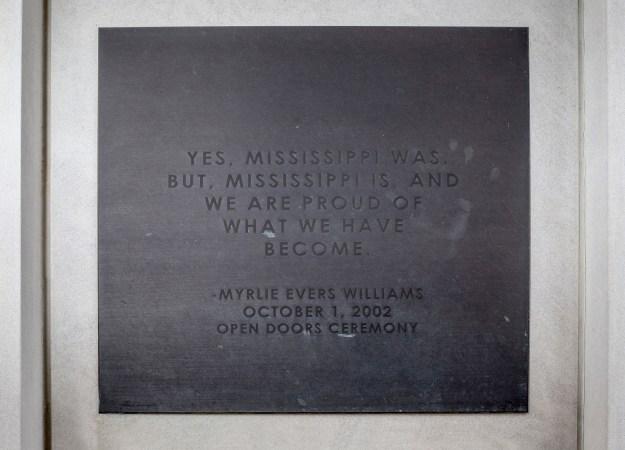

The sun rises. The rain slows. A pleasant mist is quickly enveloped by thick humidity. Cars fill the circle. Students shuffle to class. Much has changed since 1848, since violence and nearly 4,000 state marshals and federal soldiers descended on the campus during the Meredith riots of 1962. Much remains the same. There is the Lyceum, some parts unchanged since its construction nearly two centuries ago. There is the towering monument that continues to greet entrants to the Circle, engraved with the following dictum in white-gray marble: “To our Confederate Dead.” And there are black students—like Marino and Scott and an intimate community of others—who continue to disrupt the campus’s racial status quo, to question its strained and problematic history, to celebrate personal successes and growth while grappling with the weight of their hope and ambition. Despite challenges and setbacks, they persist, demanding that the university continue to create space, amid the magnolias and immaculate fraternity houses, amid the neatly kept gardens and lakes, to reckon with its ghosts.

I am walking with Marino and Scott beneath deep greens and gray clouds on a summer afternoon in the Grove. “So many black folks have come through this place,” Scott says. “I am coaxed by them, drawn to them. We did this, in some ways, for them.”

Marino adds, “Our being here and being black and being the best at everything we do is probably the only memorial [those black folks] will ever get. We say their names, we remove the symbols. … For us it was the flag. For someone else it’ll be the statue. That is how we memorialize them.”