We stood beside the car on a dirt road in the Flathead National Forest, peering east at a silver ribbon of river. It shimmered through a forest of pines flecked with gold larches that stretched clear to the base of blue mountains. We could hear them but we couldn’t see them: wolves

I was back in my home state inside an expansive region I call the Montana Triangle. I was with my best friend Lido Vizzutti, a photojournalist. We became neighbors in middle school. Montana is the state where, in summers, we slept in a field between our houses, climbed hills looking for wildflowers, played in the middle school band, and in high school began taking our first road trips together as a reporter and photographer pair.

We were at the start of an epic, week-long 1,200-mile road trip to see in one loop three of the most majestic and dynamic large, preserved landscapes on planet earth: Glacier National Park, the American Prairie Reserve, and Yellowstone National Park. A terrestrial constellation—the Montana Triangle. And we would string these wild places together by stopping in between to eat good food and drink great beer. Our purpose was to reconnect with the landscape that reared us alongside each other and add another adventure to our long friendship.

We were near Glacier, our first star in the Montana Triangle. Because I live in New York City now, I was extra eager to watch wildlife, catch trout, see the last glaciers before they inevitably melt, hike, camp, and let my sense of the possible be rejuvenated by nature. After stints in Tennessee and London, Lido is now back in our hometown, Missoula. At the time of our trip, he and his wife were only months away from welcoming their first child (lest there be any question how tremendous she is). Meanwhile, I’ve been away for 15 years. But I still miss Montana like mad. Lido and I were probably talking about one of these facts when we were silenced into goosebumped reverie by the wolves’ arias.

“That,” Lido said, grinning, with eyebrows raised, “is legit.”

At the top of Going to the Sun Road, the pièce de résistance of the million-acre national park, we hiked past families of white mountain goats and tan bighorn sheep to a cobalt lake ringed by jagged crags. Fat cutthroat trout with black speckles and red chins rose to the flies we cast. A waterfall in the Many Glacier Valley cascaded in front of an impressive pyramid-shaped peak called Mount Grinnell. On the Blackfeet Nation Reservation, Lido spotted a family of husky black bears in a grove of cottonwood trees blazing in fall orange. We were just getting started.

The tone of our trip was set the first night. After campfire-roasting bison sausages bought at a classic market called M&S Meats, we walked to the brisk shores of Bowman Lake. In the crook where the mountains open to a sky of a trillion stars, the Northern Lights danced a celestial fandango—ribbons of yellows, greens, and purples. I came into the Montana Triangle with high expectations. It would surpass them all.

The Montana Triangle is massive, and that’s the point of taking a trip like this. About the size of Maine, the Montana Triangle spans the Continental Divide and contains both the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains. In addition to national parks and forests, it encompasses college towns, farm towns, Native American reservations, wildlife refuges, snow-tipped mountains, cerulean lakes, shimmering wheat fields, river valleys, supersize ranches, 20-acre ranchettes, marvelous breweries, welcoming bakeries, retro drive-ins, and truck stops clanging with video Keno. It’s also the heart of America’s most intact ecosystem outside of Alaska. Despite the metastasization of housing subdivisions in what used to be horse pastures, Montana is mostly still wild, open, and awesome. It is what one of her greatest journalists, Joseph Kinsey Howard, declared in the title of his 1943 book, “Montana: High, Wide and Handsome.”

In 2016 the Montana Office of Tourism and Business Development finished a popular advertising campaign. It boiled down to just seven letters and two words: “Get LOST.” The words, printed on green, Montana-shaped decals, shouted from the bumpers of diesel pickups, the sides of tall grain silos and even the flanks of commuter trains in Chicago. I always thought the campaign was clever because it could be read both as a beckon to harried Montanaphiles and a tell-off to anybody whose soul isn’t stirred by the sight of a bull elk on a mountain ridge. But the word “LOST” also always made me think of the Bermuda Triangle. A look at a map made me realize, though, that Montana has a triangle all its own. A massive scalene one, with a perimeter drawn roughly by Highway 2 to the north, Highway 191 to the east, and Highway 93 and Interstate 90 to the west. They link the vertices: Glacier, the American Prairie Reserve, and Yellowstone. Incredible landscapes, teeming with wildlife that are emblematic of some of the most audacious American conservation efforts of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

Wild places draw pilgrims, and tourism is Montana’s second biggest industry, behind only ranching and farming. More than 12 million people visited Montana in 2016. Glacier and Yellowstone both also shattered attendance records in 2016 as the National Park Service celebrated its centennial. A combined seven million people visited them. One was the tourist from Asia who waved his hand at me to take a better photo of Yellowstone Falls. Another was the man I giggled at for taking selfies in front of bighorn sheep in Glacier Park, who turned out to be TV personality “Jungle” Jack Hanna. Will Hammerquist, 36, co-owner of the rustic Polebridge Mercantile on the western edge of Glacier described the parks as, “bursting at the seams” and added, “the smart business decision would be to expand.”

Montana has more land than all but two contiguous states, but only around a million residents, giving it the seventh-smallest population in the nation. Politically, it went for Republican Donald Trump for president but re-elected Democrat Steve Bullock for governor (we saw far more signs for the latter than the former). The Montana Triangle is nothing if not dynamic. It holds the largest natural body of water west of the Mississippi River, Flathead Lake; the hardscrabble mining town of irrepressible character, Butte; The Flathead, Blackfeet, Chippewa Cree, and Fort Belknap reservations with their poignant museums, cultural centers and wildlife. And not far outside the triangle, the Fort Peck Reservation, which in 2012 became the first of three northern Montana reservations to reintroduce pureblood bison, and the Crow Reservation, where you can see the grave of George A. Custer. There are hot springs, working ranches, wilderness areas, veteran’s memorials, minor league baseball stadiums, and miles upon miles of trout streams.

But it is the blue highways connecting the people to this place that seduced novelist John Steinbeck to gush in his 1962 book “Travels With Charley”: “I am in love with Montana. For other states, I have admiration, respect, recognition, even some affection. But with Montana it is love.” So I bought $17.85 worth of carbon offsets and Lido and I loaded up our borrowed four-wheel-drive vehicle with tents and sleeping bags. Also a spare tire, a sturdy jack, extra water, good boots, bear spray, binoculars, and paper maps for the stretches when our cell phones could bring us neither directions nor distractions.

“I love it when the back of a car I’m riding in has a cooler, firewood, and two fishing poles,” Lido said as he slammed the hatchback.

And in late September 2016, we set out to get LOST.

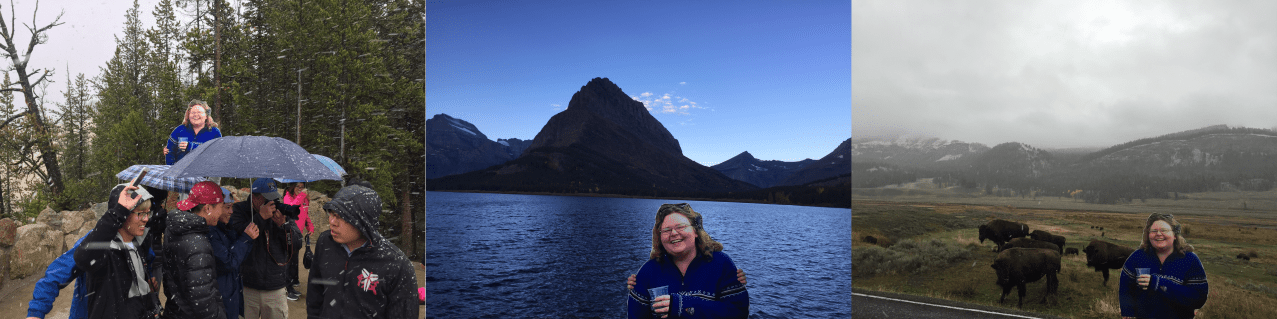

We brought another passenger with us too, of sorts. A Montana journalist we admire, Kristen Inbody of the Great Falls Tribune, was laid up in recovery after an unexpected surgery. To keep this member of our tribe on her statewide beat, we chauffeured around a life-size cutout of her, grinning and holding a cup of green beer. We photographed her likeness in front of Glacier Park’s Swiftcurrent Lake and beside a hay bale in the Flathead Valley decorated like the Star Wars character Yoda. We snapped her with a herd of bison in Yellowstone and in the town of Cut Bank beside a giant penguin statue (commemorating a record low temperature). Also in front of the monstrous, toxic Berkeley Pit in Butte and with a Tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton inside the Phillips County Museum—a Montana treasure in the small town of Malta. We drank with her inside Spencer’s Hi-Way Bar and Grill in the pint-sized town of Hingham. Owner Mike Spencer keeps on his wall a framed autographed photo of Vanna White promising him a hug when she comes to visit. He’s still waiting. But he happily wrapped an arm around our friend and grinned for our camera. This being Montana, nobody called us weird.

We were confronted only once. On a rough dirt road 50 miles from any pavement on the edge of the American Prairie Reserve, with its Great Plains horizons so awesomely vast they’re like the mountains of Glacier Park tipped on their sides, we stopped and watched the setting sun turn the universe tangerine, then magenta, then lavender. A man whose beard and hair were warrens of straggle slammed his brakes in a red pickup truck with a cattle dog hanging out the passenger window. Did we miss a “No Trespassing” sign? I wondered, as my brain flashed to road signs we passed that were pocked with bullet holes. The man grunted that he wanted to know what we were doing.

“Just watching the sunset,” Lido said.

“My kind of guys,” the man said, shifting his rig back in gear. “If you’ve got cold beers now’s the time to break them out.”

The American Prairie Reserve, the eastern star, is becoming the largest wildlife reserve in the lower 48 states. A private nonprofit founded the reserve in 2001 and restored bison to this Missouri River landscape in 2005 (200 years after Lewis and Clark first spotted them here; just a few decades before they were all exterminated). The American Prairie Reserve has welcomed the public onto more than a half-a-million acres of land protected for bison, elk, antelope, mule deer, sage grouse, prairie dogs, and ultra-rare black-footed ferrets. Through the tried-and-true park building method of buying ranch land from willing sellers at fair-market value and connecting expanses of public rangeland, the American Prairie Reserve hopes to one day grow to more than 3 million acres. It’s exactly the place western novelist and historian Wallace Stegner advocated for in 1960 when he wrote that America needed to protect “the vanishing prairie” where the sky, “came clear down to the ground on every side, and it was full of great weathers, and clouds, and winds, and hawks.”

What the American Prairie Reserve lacks is amenities. No hotels, gas stations, or park rangers. Lido and I learn this comes as a shock to another species repopulating the prairie: tourists. In our campsite, we met Jim and Mary Panttaja, who caravanned from Berkeley, California and were surprised to find the American Prairie Reserve so big, open and…empty. It’s 21st-century conservation, I said. The frontier. Lido and I then hiked out toward groups of bison, mule deer, and antelope—always sending them stampeding and bounding away. We tracked a fat coyote with binoculars through tufts of blue grama grass, and we chuckled at squeaking prairie dogs playing peekaboo from their holes. We crossed a range called Sun Prairie, spiked with prickly pear cacti and sounding with meadowlark trills, to a giant, red boulder that was deposited during the last ice age. Ancient Native Americans chiseled it full of indecipherable petroglyphs. Lido reasoned it was the prototype for Google Maps. That night a storm ripped in and nearly tore away our tent. Whips of lightning lashed the sky, wind hurled rain sideways and the earth shook from thunder. Great weathers, indeed!

When we drove out in the morning I looked back on the American Prairie Reserve and realized that many of its quintessential features—the open range administered by the Bureau of Land Management, the enormous Fort Peck Reservoir (with more miles of shoreline than the California coast), and the neighboring million-acre wildlife refuge named for frontier painter Charles M. Russell—are all legacies left by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was from New York, the place I came back to Montana to try and forget. I recalled that Glacier, too, owes its existence to a New Yorker. Conservationist and Native American ethnologist George Bird Grinnell dubbed it “The Crown of the Continent” and lobbied congress until it was established in 1910.

Then there is the patron saint of American public lands, Theodore Roosevelt, an action hero of a president whose outsize influence on Montana allowed native sons like me to be raised around millions of acres of protected parks, national forests, and wildlife refuges. He was a New Yorker, too. Growing up I assumed that Montana was inherently better than every other state because it is so beautiful. “Montana, glory of the west/of all the states from coast to coast you’re easily the best,” go the lyrics to the state song Lido and I played over and over in school band. A 2014 Gallup poll showed Montanans and Alaskans have the most state pride of any Americans.

But learning that Montana owes the preservation of its wild beauty to a few chummy romantics who lived in Manhattan made me feel conflicted. As a transplanted New Yorker, I felt proud. As a native Montanan, I felt parochial. It was as if my sense of belonging had gotten LOST.

We turned on one of my favorite radio stations, KGVA, broadcasting from the tribal college on the Fort Belknap Reservation. The hokum I sometimes hear about the spirit of Native Americans being everywhere on Montana’s prairie is actually true here: radio waves. Through the speakers blasted a traditional powwow song of drum thumps and high wails. It segued seamlessly into an electric anthem by Patti Smith. I would never have imagined them working together. But they do, and it rocks.

Driving south on the eastern flank of the Montana Triangle, we stopped in Lewistown at a drive-through hamburger stand built in 1952 called the Dash-Inn. We scarfed Wagon Wheels—tasty burgers encased by two pieces of white bread so they look like flying saucers. We enjoyed food as varied as the topography in the Montana Triangle. On the trendy side, we tried Texas toast slathered in avocado and drizzled with coconut oil at Black Coffee Company in Missoula. And rich biscuits and gravy at Gil’s Goods in Livingston. And smoked prosciutto pizza with Grana Padano paired with cauliflower seasoned with cayenne and capers fire-baked inside a cast-iron skillet at Blackbird Kitchen in Bozeman. On the workaday side, we gobbled thick, savory bison burgers at Miners Saloon in Cooke City. We quenched our thirsts with cold, gold pints poured at Kalispell Brewing in Kalispell and at Triple Dog Brewing in Havre. Not for a second did we regret devouring warm donuts dripping with powdered-sugar glaze at Windmill Village Bakery in Ravalli (special ingredient: mashed potatoes). Or sweet bear claw pastries baked fresh at the Polebridge Mercantile in Polebridge. Or the secret-recipe huckleberry pie at the Two-Medicine Grill in East Glacier. We would, however, regret eating the pickled pork hocks and turkey gizzards from the jars behind the bar at Maloney’s in Butte.

When we pulled into the river town of Livingston, a historic gathering spot for ranchers, railroad workers, and poets, Lido, the best kind of colleague, perceptive, funny and mindful, sprang for a night at the rustic-chic Murray Hotel.

We entered the lobby to check in. We nudged past upholstered furniture and a stuffed bison head, but the place was choked with well-dressed guests at a wedding reception. I was in the same clothes I had worn for days to hike, sleep and drive 800 miles. My innate Montanan sense of not wanting to impose converged with insecurity instilled by New York about not being dressed properly. My instinct was to hurry through and vanish.

At the reception was a bear of a man named Scott McMillion, editor of a vibrant magazine called The Montana Quarterly. I once wrote an article for him about a young woman from Montana’s Blackfeet Reservation whose photos were shown at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. But I had never met him in person. When he saw me he strode over, parting the crowd. I held out my hand, expecting a shake, but was instead engulfed in a hug. Into my hand, Scott slapped a cold beer from the reception provisions and told a story, doubling himself over in laughter, about a man who tried to calm an ornery grizzly bear with pot smoke. The bride and groom welcomed Lido and me to share in their celebration. Hours later we closed down the bar, old friends, new friends and a two-dimensional friend from the back of our car. I was amazed at how we were treated. It took Lido to explain the obvious.

“That’s Montana,” he said, and repeated himself because I had forgotten. “That’s Montana.”

Yellowstone, the southern star in the Montana Triangle constellation, is 2.2 million acres of geyser basins, river canyons, and meadows bursting with wildlife—a solar system unto itself. Though only the northern tier of Yellowstone is technically inside Montana’s border, the place is a pillar of the state’s spirit. Nearly every Montana map includes it. Yellowstone became the world’s first national park in 1872 and since then, more than 6,500 other parks in almost 100 countries followed its lead. This fact fills me with immense patriotism.

The animals we saw in the Northern Range just got bigger and more majestic. A bluebird flashed sapphire. Ravens swooped so close we could see they’re not black, but a violet so deep it’s iridescent. A great gray owl behind a curtain of snow on a pine branch grabbed us with its bright yellow eyes. We watched herds of elk, and of bison—descendants of the only 23 bisons known to have survived the shameful mass slaughter of the late 1800s. Just east of the Lamar Valley, a world treasure if ever one existed, at the base of foggy Abiathar Peak, we saw a cow and a bull moose face each other and appear to kiss. With that moose smooch, we had seen every big, wild ungulate species in Montana.

Near the junction of the Lamar River and Slough Creek, we pulled over near a cluster of cars on the shoulder and joined a gaggle of tourists with long spotting scopes. Somebody thought there could be a wolf by the far timberline. This caused a great stir. Data shows that in 2015 the term Googled most often from inside Montana was “wolves.” I felt excited too, remembering the chorus that we heard at the beginning of our adventure in the Montana Triangle.

Beside us, peering through oversize binoculars was Stacy D. Allen, the chief ranger at Shiloh National Military Park in Tennessee. He wore a slouch hat, a riding jacket, and a burly mustache that made him look uncannily like Teddy Roosevelt. Every fall he comes to Yellowstone for three weeks, he said, to soak in the big landscapes of the Montana Triangle and watch wolves.

“They’re not too far away from homo sapiens in their behavior,” he said. “They need large landscapes, and we have always needed them too, I think it’s primal to desire space and freedom.”

He put into words better than I, the draw of the Montana Triangle.

Soon we had to go. I had New York deadlines to meet. Lido had the next generation of Montanans to raise. But then, in the way trout can appear out of the cobble bottom of a creek, a family of seven gray wolves and four black ones emerged from tufts of big sagebrush. They threw their snouts skyward and let fly their song. The theme music of our trip repeated as the credits rolled. I took stock in that moment at my place in the world. Sage scent in my nose, crisp wind numbing my skin, friendship warming my heart and wild Montana in my ears and eyes. I didn’t feel lost in the Montana Triangle. I felt found.