Like most kids my age—I’m 23 but am still going to call myself a kid—I came upon country because someone older than me listened to it. My grandpa and I would ride around in his green Chevy and listen to Kat Country 103 when they still played the likes of Johnny Cash, George Strait, and Reba McEntire, but country never really stuck with me. Then when I moved to New York City in 2015, I started to listen to country as a subconscious way to rebel against my new cosmopolitan life and peers. It wasn’t guys singing about sittin’ on their tailgates and drinking Budweiser that brought me back to country. It was women singing about actual small-town life and not giving a shit about society’s standards.

If you look at the complexity of the country music produced by men in 2000s, you’ll see that, besides a few outliers (like Sturgill Simpson and Chris Stapleton), many of the songs are repetitive and simple in arrangement. Like every genre, country makes room for experimentation, but the bones should still be there. That is lacking in “bro country”—a subgenre that relies heavily on either rap, rock, or pop music. There is nothing more nauseating to me (and to this dude) than listening to a guy try to rap with a twang so his music can still be called country. Bro country also has an unfortunate predilection for lyrics about hot “girls” (as opposed to women).

Meanwhile, country’s women, by and large, are preserving the genre’s original sound and boundary-pushing lyrics. Unfortunately, they’re not getting their due.

How did we get here? As country progressed through the ’60s, ’70s, and even the early ’80s, the music became more electric but never strayed far from the classic productions. In the late ’80s, mostly male acts began incorporating a more rock-and-roll sound into their music by adding the always popular power chords and even hard-rock guitar solos. Acts like Travis Tritt, Alabama, and Eagles ushered in the rock sound that would become a revolution in the ’90s and early ’00s—the early stages of bro country.

Meanwhile, Reba McEntire, the Judds, and Patty Loveless held it down for the women during the ’80s, leading to girl-power ’90s country like the Dixie Chicks. The ’90s and early ’00s also welcomed pop-influenced country, performed by the likes of Shania Twain, Faith Hill, Martina McBride, and Trisha Yearwood. By the way, some of these women are among the top-selling country acts of all time.

And yet bro country makes up most of the current country-music airwaves and charts. At any point in the last five years, you can spot maybe one or two solo female acts in the top 20 on the Billboard country charts. Between 2012 and 2015, not one female artist held the No. 1 spot on the list until Kelsea Ballerini’s “Love Me Like You Mean It.” In contrast, in the mid ’90s women represented 32 percent of the artists on the singles charts.

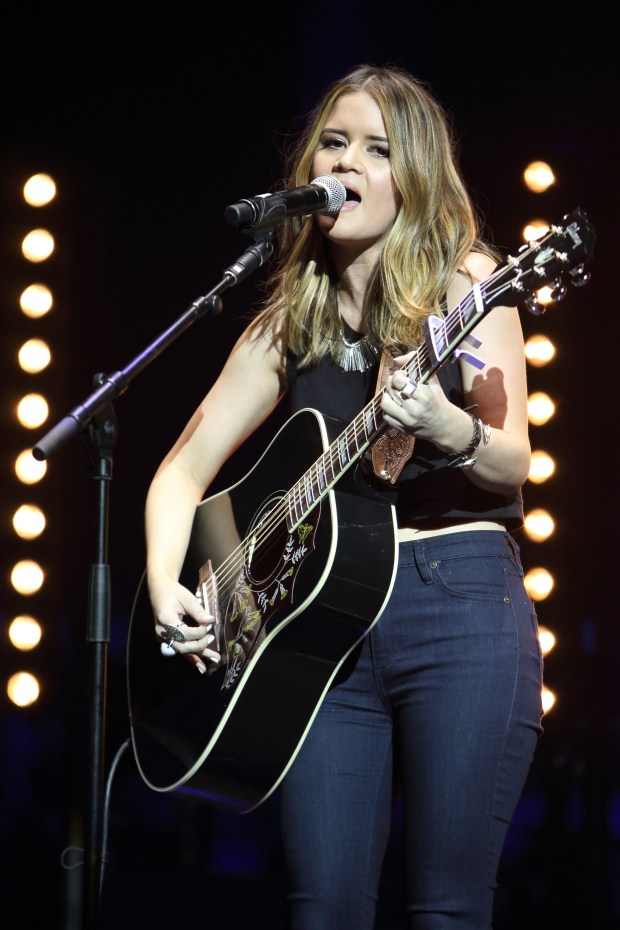

Despite this, there is reason for cautious optimism. In 2016, three solo-female acts—Maren Morris with her debut studio album, Miranda Lambert with her sixth album, and Dolly Parton for the first time since 1991—landed number one spots of the Top Country Albums charts. In April, Lauren Alaina became the second female artist in seven months with a number one song on the Country Airplay Chart.

Still, as of August 31, the number one song for 30 weeks has been Sam Hunt’s “Body like a Back Road,” which is about a woman with a curvy body that he has gotten with. Please listen to this, and tell me what you think is country about it besides the fact that he has a slight twang.

This disparity may be partly due to some DJs favoring male artists. Scott Borchetta, CEO of Big Machine Label Group, said in an interview with Rolling Stone that radio is still the number-one way that people discover new country music. That gives DJs a lot of control over who makes it. In 2015, one of country’s most popular radio DJs, Keith Hill, called female country singers the tomatoes on top of a man-salad.

More specifically, he said, “The lettuce is Luke Bryan and Blake Shelton, Keith Urban and artists like that. The tomatoes of our salad are the females.” He advised other radio DJs: “If you want to make ratings in country radio, take females out.”

I found this slightly comical, because whose favorite part of a salad is the lettuce? If it were socially acceptable, I would eat a bowl full of croutons. But for a genre that has largely progressed due to the ingenuity of female artists, that statement was a punch to the gut. Sexism is commonly found in country music—Hill just happened to say it publicly.

And women deserve recognition for keeping the real country sound alive in today’s music scene. Classic artists like Dolly Parton, Loretta Lynn, and Wanda Jackson are still going strong, and a new crop of female country singers is holding it down.

Miranda Lambert is currently one of the biggest performers in country music in album and ticket sales, streams, and awards. Her use of power chords and heavy bass also leans Southern rock, but her slower songs evoke strong ’70s country. For example, her song “Tin Man,” off the 2016 double album The Weight of These Wings, evokes an early folk-country sound reminiscent of Emmylou Harris. Lambert is also in a trio called Pistol Annies, with Ashley Monroe and Angaleena Presley, that has a great classic sound. Their 2011 song “Hell on Heels” resembles the “outlaw” country of the late ’70s, mixing bluegrass harmonies with subtle guitar riffs for an eerie western hit.

Sunny Sweeney, while not as popular as Lambert, has been around just as long. Her song “Pass the Pain” in particular is a sad honky tonk ballad that has strong roots in late-’60s country. Sweeney’s voice has some twang, but it isn’t kitschy. She doesn’t sound like she is trying to sing at the Western-themed root-beer parlor in Disneyland.

Margo Price is one of the newer performers in mainstream country, though she’s still pretty indie. You may remember her from the Nashville episode of Parts Unknown. Her voice sounds like an early Dolly Parton or Tammy Wynette mixed with honky-tonk rhythm and the sad stories that resemble George Jones’s work. Similar to Price, Dori Freeman is evoking sounds from the past. Her debut album, Dori Freeman, was released in early 2016 and sounds like it might be the sequel to Loretta Lynn’s Coal Miner’s Daughter. Freeman’s album is slower and hinges mostly on her soft love songs, but she still has upbeat, punchier songs similar to Lynn’s.

Some women are pushing the limits lyrically while keeping a traditional country sound. Even more reminiscent of classic country, their music has melodies that appease longtime fans but themes that force older Americans to reckon with social change.

In the book Country Music U.S.A., Bill C. Malone and Jocelyn R. Neal write that the women of country music really found their voice in the ’80s and ’90s. “Women not only emerged as independent stylists and architects of their own careers, they also began to comment more freely on issues that are relevant to their lives.”

In mainstream pop the lyrics of these artists’ songs wouldn’t be controversial, but in a genre often tied to Christianity and conservatism, these women are causing a stir.

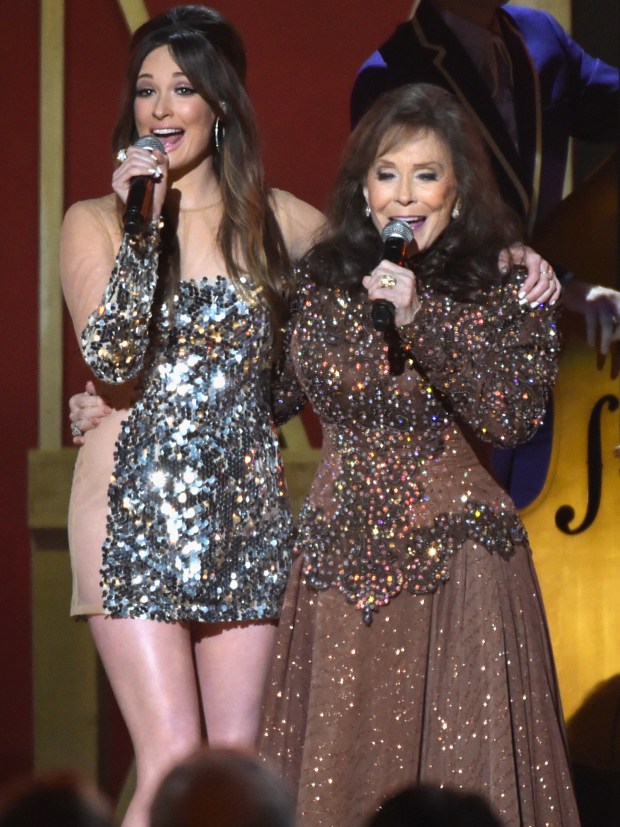

Take Kacey Musgraves, for instance. In her 2013 breakthrough album she sings about a small town living in a perpetual cycle, having a friend with benefits that she doesn’t have feelings for, and telling the person that she used to love to leave her alone. But her song “Follow your Arrow” really pushed the envelope. The lyrics explore how it’s important to just be who you are, whether that means smoking pot or coming out.

Make lots of noise

Kiss lots of boys

Or kiss lots of girls

If that’s something you’re into

When the straight and narrow

Gets a little too straight,

Roll up the joint, or don’t

Just follow your arrow

The song didn’t get a lot of airtime on country music radio stations, but the track did earn Musgraves a Country Music Award for song of the year. She went on to win the Grammy for best country album as well as best country song for another track on that album.

What was truly different about the song was that its success didn’t depend on upbeat pop beats or synthesizers. She made the song seem like it had been around for years. Her whole album focused more on story-driven lyrics with meaning and used more complex arrangements than those of the top country songs.

Maren Morris, a newcomer to the country scene, mixes a pop sound with lyrics that are still poignant. Her song “I Wish I Was” is about not being the woman she wants to be and not being able to force herself to love someone just because that person loves her. (I like to think the song goes out to all the guys who believe there is a friend zone.) When she said the word shit in her song “Rich,” country music about did itself in. When Billboard asked her about it, she said, “I’m so flattered when people laugh at my songs because I use the word shit in them, but it shouldn’t be that shocking, because it’s like real-life conversation.”

And Musgraves and Morris weren’t the first to challenge the male-dominated messaging pervasive in country music. Other notable incidents that have made waves in the political sphere include the Dixie Chicks’ famous fight with former President George W. Bush, which essentially they claim got them blacklisted from Nashville, numerous songs about abusive relationships, and odes to female empowerment (Loretta Lynn sang about the pill in 1975!).

Somewhere along the line, some of country’s men stopped singing about things that actually matter. They turned to singing catchy, meaningless songs, and they only ever comment politically if it’s to say, for instance, as Toby Keith did a year after 9/11:

Justice will be served and the battle will rage

This big dog will fight when you rattle his cage

And you’ll be sorry that you messed with

The U.S. of A.

‘Cause we’ll put a boot in your ass

It’s the American way

Country artist Zac Brown, like myself, thinks that the people deserve better country music than that. Brown slammed Luke Bryan‘s song “That’s My Kind of Night,” which is about a nice country boy looking for a girl who wears Daisy Dukes, drinks beer, and likes riding in trucks. Brown wasn’t criticizing just Bryan, but also the songwriters and how they make different arrangements of the same song. He said, “If I hear one more tailgate-in-the-moonlight, Daisy Duke song, I’m gonna throw up.” Me too, Zac. Me too.

What Brown doesn’t address is that there is already better country out there. It’s created by women.

Tyler Elmore is a social media editor at Parts Unknown. The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers.