Drenched with frequent monsoon rains, the usually arid landscape along the highway to Kilinochchi, a town at the very north of Sri Lanka, is now lush and green. My friends and I stop for tea near the Thandikulam railway station as another brief but violent downpour begins. Ram, the shopkeeper, owns only three cups, so his other customers will have to wait for us to finish. On his table is a local newspaper, dated October 22, 2017. It is turned to a page with a picture from the wedding of Velupillai Prabhakaran, the deceased leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

Life is much better since the war ended, says Ram, a Tamil who survived the 26-year-long conflict that pitted LTTE, predominantly Tamil, against the Sri Lanka Armed Forces (SLAF), predominantly Sinhalese. But while life is much better, crime and sex offenses against women are rampant in this age of corrupt politicians, as opposed to iron-fisted rebel leaders. “Prabhakaran had many faults, but he had no mercy for wrongdoers,” Ram explains.

One of those faults was brutality toward his own people. During the LTTE’s reign in this area, if Ram were seen by one of the organization’s members while talking to Sinhalese from the south, he probably would have been taken away on suspicion of giving information to the enemy, and then most likely he would have been shot after being tortured. In fact, he asks that we not reveal his last name. Showing even the slightest sign of sympathy for the LTTE, he says, can get you into trouble with the government security forces, who now control the area.

We are in Vavuniya, the first major city in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka, following travelers from the south along the A9 highway to Jaffna. It’s a first for many: The iconic road, which links the north to the south, only just reopened in 2009 after being closed for 19 years. While eight years have elapsed since, many southerners have still not visited the north.

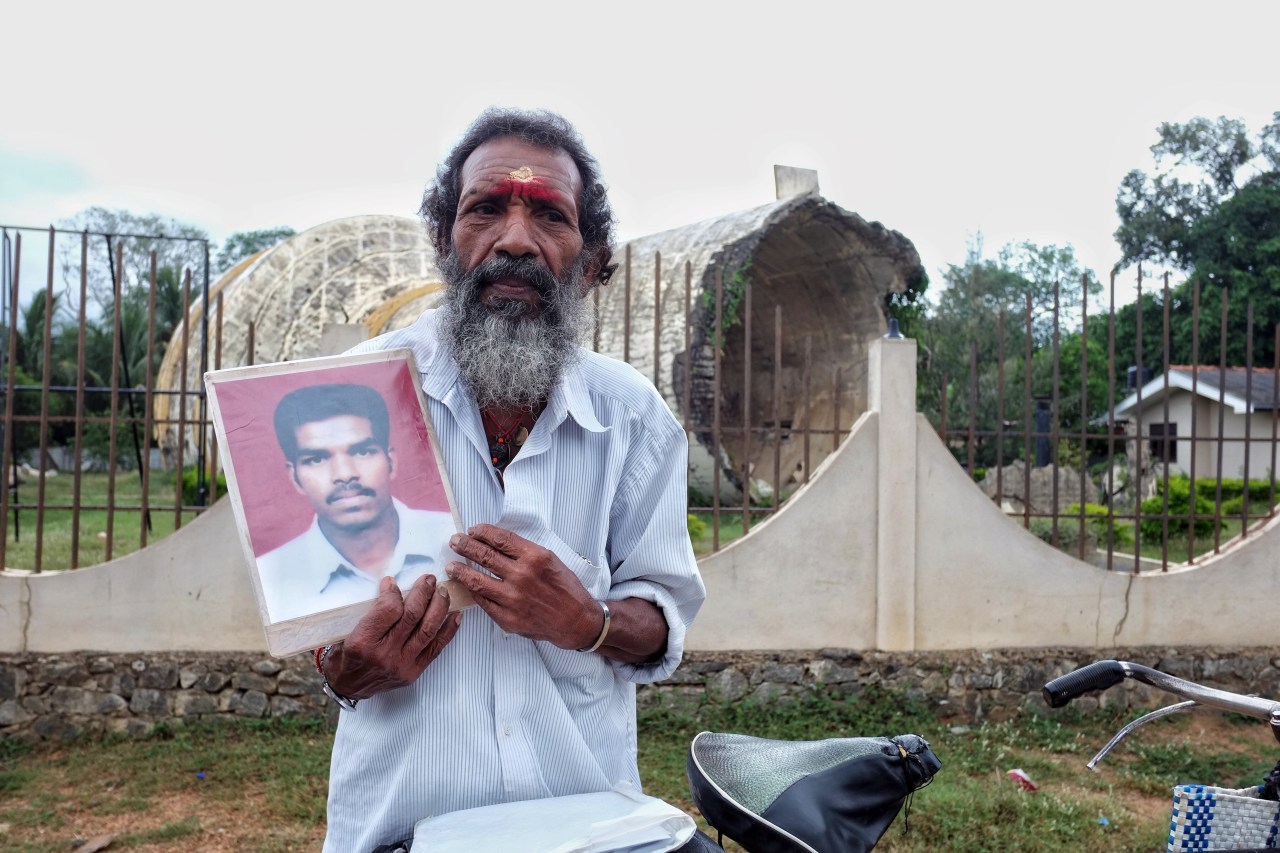

After tea we continue along the damp road to make a stop at Kilinochchi, the administrative capital of the LTTE from 1998 until just before the end of the Sri Lankan civil war in 2009. As we gaze at a water tank decimated by shelling, an old man on a bicycle stops to chat. Muddan Thavendran tells us that his son, Radeswaran, was forced to join the LTTE in 2008. He was 26 years old. He was reported missing three months later, as the war ground down to its bloody end.

Devastated and lacking closure, Thavendran is still on a mission to find his lost son. He clings tightly to three threads of hope: a rumor, a barely discernible picture in a newspaper, and the assurances of the priest at his temple. While exact numbers are disputed, the war is thought to have claimed the lives of tens of thousands of civilians, many of them during its controversial final stages. According to the latest statistics from the International Committee of the Red Cross, more than 16,000 people remain missing. The vast majority of the dead and missing belong to the country’s Tamil minority.

The road to Jaffna from Killinochchi is littered with war monuments. As at several other sites of importance in the north, many feature military-run businesses, such as souvenir and food outlets, that diminish the trickle-down of tourist income to the local economy. All of these sites glorify the victory of the SLAF.

While Tamil locals greet these spaces mostly with cold indifference, silence, or (very rarely) outspoken anger, tourists from the south flock to see them in busloads. Tellingly, the monuments frame these tourists’ visits to Jaffna, placed between traditional sites of pilgrimage on the road from the temples of Anuradhapura to the island of Nainativu, believed to be the second site in the country visited by Gautama Buddha. The war monuments are in prime position to facilitate war tourism from the south. And although Sinhalese pilgrimages to Nainativu go back decades, if not centuries, the intertwining of religious narratives with those of nationalism and state power is new.

The first monument we see as we enter Kilinochchi is also the most lacking in taste: a large, hollow cement block erected in what used to be a public park administered by the LTTE. There are cracks on the block, leading from a huge brass bullet. A soldier on duty explains that the bullet signifies the power of the armed forces, while the hollowness of the block symbolizes the emptiness of the LTTE’s struggle. “They will never rise up to cause trouble to us again,” he tells us.

To the north of Killinochchi, at Elephant Pass, stands the monument to Hasalaka Gamini, a legendary Sri Lankan soldier, along with the wrecked LTTE tank he is said to have single-handedly stopped at the cost of his life. The spot is a favorite for tourists visiting from the south, who take pictures and wonder at this soldier’s bravery. “These monuments are important for us to remember the actions of our heroes,” Dilmini Jayaratne, from Horowpathana, tells me. “Otherwise how will we mark our history?” To most Sinhalese tourists like her, this trip to the north is one of leisure and discovery. It is a chance to experience significant events of recent history and to explore a part of the island that used to be inaccessible.

But the experience of war cannot be broken down into easy binaries. Many are frustrated with the promised peace dividend; their aspirations for a better life have not been matched by opportunity. For some, wartime memories are beginning to morph and transform, as viewed through the lens of an increasingly disappointing present. In this context, the war memorials complicate peace efforts. Prasad Ramanayaka, a police officer in his 40s, on duty at Elephant Pass, agrees that the Sinhalese have a right to celebrate the deeds of their fallen heroes. “But,” he adds, stopping traffic to allow pedestrians to cross to their tour bus from the Hasalaka Gamini monument, “we must not also forget that there is a certain set of people to whom these monuments cause only grief and not happiness.”

Ramanayaka believes that the biggest barrier to peace is the ongoing dislike of the other. “The Sinhalese think that all Tamils belong to the LTTE, and the Tamils believe that the Sinhalese are so violent and brutal that they would even kill Tamils and eat their flesh. If we cannot communicate with the other, then how can we ever get to know them?” he asks. A primary enabler of these divisive attitudes is the language barrier, institutionalized by Sri Lanka’s Official Language Act of 1956, commonly known as the Sinhala Only Act. The act replaced English, a tongue that could have served as a link language between the country’s various ethnicities, with Sinhalese as Sri Lanka’s official language and gave no status of parity to the Tamil language, disenfranchising people who spoke only the latter.

Both Sinhalese visitors and Tamil locals express frustration at their inability to communicate with their counterparts. On the way to the Navy-operated ferry to Nainativu, I meet Nipun Rathnayake and his family, who have traveled all the way from Matara at the southern tip of Sri Lanka. They are buying dried fish, souvenirs, and alms for the temple from small shops lining the road, most of them belonging to Sinhalese traders.

The family has already visited the war monuments and will head back home after seeing the temple at Nainativu. They say they aren’t curious to see other sites of note in Jaffna, such as the Nallur Kandaswamy Kovil, Keerimalai, or places of cultural importance to Tamils. Yet Rathnayake says he wishes he could have communicated better with locals. He thinks that both Tamil and Sinhalese languages should be a part of compulsory education in schools.

Sitting at the waiting area for the ferry with his large family, Dushan Kandula from Piliyandala echoes this sentiment. His two children are already studying Tamil in school, “so at least if we do not know the language, they will.” In his business, Kandula must find solutions to facilitate communication. “In my line of interior decoration work, we always find it helpful to include a Tamil speaker in the team for projects in the north—this really helps the process to be smooth.”

Thulasi Gnanaprakasar, a Tamil resident of Jaffna and an engineering graduate from the University of Moratuwa, also believes the language barrier exacerbates the divide. “It’s only after I went to Colombo and learned the language that I started having Sinhalese friends, and it is only then that my perceptions about them began to change.” She is taking the ferry with her young daughter and elderly father-in-law on a visit to one of the kovils (a style of Hindu temple) on the Island. One day, she hopes, her daughter too will speak fluent Sinhalese and have many friends from the south.

The ferry takes approximately half an hour to reach the island of Nainativu, situated off the west coast of the Jaffna Peninsula and home to several sites of religious importance. Alongside the primary Buddhist temple (the Purana Rajamaha Viharaya), large kovils (including the historic Nagapooshani Amman Kovil), a church and the jummah mosque represent the major religions on the island. There is also the lesser-known Tripitaka Maha Seya with its gem-studded throne. The island is present in folklore dating to the earliest times of Sri Lankan history. Both its Tamil and Sinhalese names—it is known as Nagadeepa in the latter—allude to the ancient Naga people, who are said to have once inhabited the island.

At the mosque I meet a group of men from Colombo on a Tablighi Jamaat pilgrimage. They are taking a dip in the sea and enjoying the beach before lunch. The Tablighi Jamaat is an Islamic evangelical movement that originated in India in the early 20th century. While it has activities all over the world, it is particularly strong in the subcontinent. Members travel for days and sometimes months, staying at mosques along the way, proselytizing the movement’s beliefs.

Over a warm meal of fresh mutton biryani, the leader of the group, who is in constant dialogue with the head priest of the Buddhist temple here, emphasizes the role of local community leaders in guiding people’s attitudes toward peaceful coexistence. “Muslims could potentially have an important role to play because of our trilingual abilities.”

In 1990 the Muslims of the north were expelled in an act amounting to ethnic cleansing by the LTTE. More than 75,000 people found themselves fleeing their homes with little more than the clothes on their back. Some are now returning; and among them are people, internally displaced for nearly three decades, who are struggling to return to their old homes in the north, now caught up in land disputes.

Due to the language barrier, many tourists from the south seem to pass through the north without engaging in meaningful conversation with locals. Most interactions that happen along the road are simple, transactional conversations at shops, restaurants, or hotels. I wonder how many Sinhalese get to know the stories of locals like Ram and Muddan Thavendran? And how many return home with an elevated sense of national pride evoked by the military triumphalism on display?

At the Purana Rajamaha Viharaya in Nainativu I meet Pradeep Kumara, a Sinhalese graduate from Kurunegala who is visiting the peninsula with a friend. The two young men say that while they have Tamil friends back home, neither knows the language well enough to sustain a conversation here. Kumara, who is currently living with his father in Jaffna, is determined to use the two months he has here to change this. “I really want to learn Tamil so that I can speak to and hang out with Tamil people—only then can we understand them.”

Back on the mainland I meet Father Rashmi Fernando, a recently ordained priest based in Hingurakgoda. He is part of a large company of people, mostly comprising youth, who are disembarking the ferry and walking through the dripping tropical monsoon toward their tour bus. Fernando says that southerners should stop visiting the north in the guise of tourists. “We need to interact with the people and their culture, not just with the monuments.” This is Fernando’s first trip to the north. On future trips, he says, he would like to explore ways of how to instill these values in the youth groups he travels with.

Leaving Nainativu, we quickly drive to the famous Nallur Kandaswamy Kovil, hoping to catch it in its glory at sunset. Unfortunately, the overcast skies render everything in diffuse gray light. We catch the Chandrasekara family, from Anuradhapura, who are just leaving. When asked about their impressions of the north, the daughter Devishini observes how state institutions in Jaffna operate primarily in Sinhalese. “We have experienced how difficult it is to communicate in a language we don’t know—how must it be to have that as a part of your daily and essential experience?”

It’s her first visit to the north, but her father, Upali Chandrasekara, has been here once before, in 2010. He notes that its development is far behind the south’s: “I have seen how even children have to work here—this is really problematic.”

Indeed, language is not the only problem separating the Sinhalese from the Tamil. There is a long history of divisive post-independence power politics, static legal frameworks, unhelpful public policies, and entrenched negative attitudes that prevent true reconciliation. Still, on the road to Jaffna it’s clear that ordinary people, especially youth, are attempting to reach across the divide in the hope of better mutual understanding.