While imagery of the “American War” in Vietnam was being blasted across newspaper front pages, radio stations, and televisions in the U.S., the Nixon administration and the CIA were secretly showering its neighbors, the small, land-locked Laos, and Cambodia, with millions of bombs, aiming to wipe out Northern Vietnamese troops along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, as well as any of their communist allies.

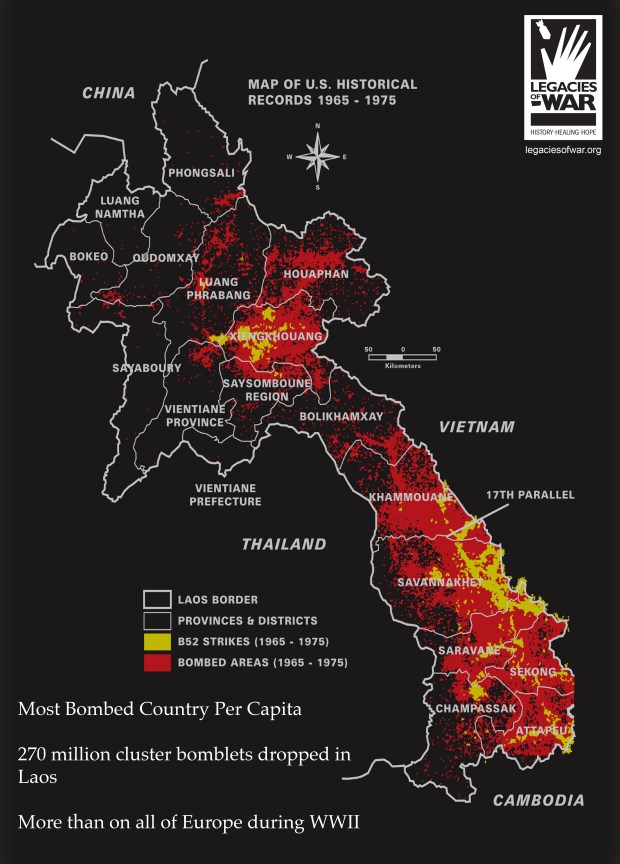

From 1964 to 1973, U.S. warplanes dropped more than 270 million cluster munitions on Laos in 580,000 intensive, CIA-run secret bombing missions. One-third of these did not explode upon impact, mainly because of the porous, muddy ground. More than 50,000 people have now been killed or injured by unexploded ordnance, also known as UXO.

Laos, known for its idyllic landscape of mountain ranges, wide rivers, and lush tropical forests, is the most heavily bombed country in history. Now pockmarked with thousands of bombed craters, one-third of the country, across all 17 provinces, is contaminated.

In the two decades demining groups have worked in the country, while the overall number of casualties have decreased, the number of children hurt or killed has increased, with kids often mistaking the small, spherical “bombies” for balls. Approximately 40 percent of all accidents involve children and 60 percent result in death.

On the banks of the Mekong River in the picturesque town of Luang Prabang, I sat down with 44-year-old Channapha Khamvongsa, the executive director of the Washington-based Legacies of War, an organization devoted to lobbying the U.S. government for financial support for bomb clearance and victim assistance in Laos.

Claire Knox: How old were you when you and your family fled Laos?

Channapha Khamvongsa: I was seven, and we were living in Vientiane when we fled to the refugee camp in Nong Khai, Thailand. We all left separately as there was suspicion about people fleeing then, and my dad actually had to swim across [the Mekong river]. Luckily we were all reunited. We ended up in Northern Virginia. I had no knowledge of what happened growing up, as my parents were traumatized, which was common, and at school Laos was just a footnote. The gap in my own history was history itself. Of course in the diaspora community there was so much PTSD and therefore high rates of alcoholism and so on.

Knox: Can you tell me a bit about how LOW was founded?

Khamvongsa: I was just embarking on my own research of my country’s history when I was introduced to the drawings that had been salvaged and collected by Fred Branfman, an antiwar activist who actually helped expose the Secret War. These incredible drawings—about 40 of them, all tattered, from the 1960s and 70s, some conveying the Plain of Jars in Xieng Khouang—were by bombing victims who had survived. They were primary evidence that was even later used in a Congressional hearing.

There was a lot of resistance from the diaspora community when we first started reaching out with our work. I’d been working with the Ford Foundation on voter participation and met a lot of Hmong people, so I had contacts. When we first started we were called “Legacies of War: a project on the secret U.S. bombing of Laos”. And yet we were totally shut down by the Hmong and Laos community in the U.S.; people didn’t want to talk to us—“why do you want to bring up war”, they’d say. They fought on the other side, with the U.S., and were still very angry about the loss of their country and their families. Anything they thought would help the new government of Laos was shut down. So we had to first acknowledge that war sucks on all sides, and if we were going to help, we could either just deal with physical remnants of war—removing bombs—or we could help communities heal, that’s the only way we have been able to mobilize so many supporters in the U.S. So then we started a traveling exhibition of the drawings and we archived and formatted them. And then through that, we had a lot of Lao-American artists come to create new works of their experiences as refugees and wartime. So it developed into almost a collective of voices who could showcase and highlight their experiences and memories of war and displacement. The drawings were the anchor and the visual that was needed to reconnect.

Knox: You were asked to help facilitate President Barack Obama’s September 2016 trip to Laos—why was his visit so significant?

Khamvongsa: The mobilization for that to happen—he had over 1,000 staff here—was incredible to witness. At four days, this was one of his longest trips in any one place. They flew into tiny Luang Prabang airport on Air Force One—imagine the logistics of that—and he even traveled around in The Beast [the U.S. presidential car]. Before that experience, I’d had little to no exposure in how the media works. I was responsible for a lot of media coordination during this visit though. I even learned the word ‘fixer’ – I didn’t even know what that term was, but apparently, I became one, slash producer, slash everything else.

Knox: And he thanked you in his speech?

Khamvongsa: Yes, I was about five feet away from him. It was quite emotional because his address at this second, more intimate speech [his first was a bigger event at the Luang Prabang cultural hall] was at the COPE visitor center—these guys work in UXO victim care, support, and prosthetic limbs. So this speech was really an address to the people of Laos about U.S. obligation and responsibility and moving forward, and how the U.S. had to do right by the people of Laos. He also talked about the implications of war, its impact and how better decisions need to be made about how and why we go to war. To me, it seemed like a reflection and, perhaps, tied into regrets about the Middle East. This is all part of the legacy he wanted to leave behind, with Cuba, with Laos. There’s been tremendous attention and awareness on Laos since his visit—all the print, all the radio, all the TV media.

Knox: How have recent political events affected the issue of UXO in Laos?

Khamvongsa: So Obama’s visit in September concluded with the wonderful news that he’d allocated $90 million of funding to assist with the UXO issue in Laos, spread out in $30 million installments over three years or three budgets. He’d backed up his visit with a commitment and it was huge. And then, the election happened [which saw Donald Trump elected as president]. So we had this very quick shift in our mood. Suddenly the funding was at risk. We’d worked so hard for it, lobbying congress. So by January we were back out on The Hill and making triple the amount of visits to both Democrats and Republicans. As we landed in Laos a few weeks ago, we heard the news that the second installment of $30 million had passed through the budget, so there were collective sighs of relief.

Knox: When did you first realize the true devastation caused by the American bombing?

Khamvongsa: On my first trip back to Laos I was with my mom and sister. We spent much of the time visiting temples to pay tribute to our ancestors. It was a beautiful trip but we didn’t get to explore much of Laos outside our family homes and temples. I first felt the impact of the war when I met a grandmother called Gai Meng in a very remote village called Ban Toumlan in Saravan, we had to cross rivers, mountains—it took three hours to get there.

Just a few weeks before I visited, she was working in her garden, and she heard an explosion. She came running around, just in front of her house, just several feet away from her loom were two bodies. And she recognized one of them as her neighbor’s kid, and the other was her grandson, Sai Tai, who was 13 years old. Sai Tai’s body lay limp. The neighbor was not even breathing, he had died on the spot. Sai was still breathing, but his body had been blown apart. She picked him up, put him on the back of a motorbike, and they drove to the nearest clinic, which was about 30 minutes away. By the time she got to the clinic, Sai had already died. When I visited her she was still very distraught but I asked her to share the story, and later I asked what we could do to help. I had commented on how beautiful her textile was, her weaving, and she said that maybe I could take it back to America, and let people know what I had heard from her. So we now distribute squares of this textile at our meetings. Even though she is so far away, and I don’t know if I will ever see her again, it is so important to share her story and remind all of us that we are all responsible, that we need to tell it forward. I love the sheer determination and practicality of Lao people. No matter what tragedy they’ve experienced, they find ways to move forward and with such grace, dignity, and humor.