Ceci Bastida lives, as many of her fans do, on both sides of the border. From Tijuana but based now in Los Angeles, the Mexican rock star plays to a demographic in limbo, people who may work on one side of the border but live on another, who may have their heart in San Diego but their family in Ensenada, or vice-versa. So it’s only natural that when she sings outside of her solo act, she does so with a band that celebrates something the community on both sides of the border care deeply about: Steven Patrick Morrissey—outsider, immigrant, and former frontman of The Smiths.

Bastida is a member of the Tijuana-based Morrissey-tribute band Mexrrissey—an ingenious consummation of the much-commented on Mexican and Mexican-American love affair with the poetry and raw emotionality of Moz’s music.

Take, for example, Bastida’s ethereal Spanish-language version of Morrissey’s 1988 classic “Everyday is like Sunday,” called “Cada Dia Es Domingo.” From the song’s music video, it is clear that Mexrrissey is a distinctly Mexican band, down to the brass instruments more typically found in mariachi music. But they filmed in Morrissey’s hometown of Manchester, draped in a haze of British fog.

Much ink has been spilled about the genesis of this grassroots love for Morrissey, who does not speak Spanish and did not seem particularly aware of his cult following among Mexicans and Mexican-Americans until recent years. As a non-Anglo Angeleno who shares this affection, I can at least hazard my own guesses at where it comes from. Maybe it’s the poetic anxiety and loneliness underlying his lyrics that surpasses the boundaries of tribal nationalism and speaks to a universal human truth. Then again, maybe this is why I love his music, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this.

Little Jesus is a popular indie rock band from Mexico City. Their lead singer, Santiago Casillas, sees Morrissey as one of the band’s influences. “Personally, I like his lyrics, because he tells stories in a really cool way. He doesn’t always structure it verse-chorus-verse-chorus or care about catchy choruses. He gives more importance to the story—like in ‘First of the Gang to Die.’ It’s not even his story he’s telling.”

It’s also about sound; whenever Casillas uses a chorus pedal at the piano, he thinks of Morrissey.

For Bastida, there’s a deeper resonance as well. “I think Mexican people love melodrama, we tend to have a very dark humor,” she says. “We connect with [Morrissey’s music] because it doesn’t seem that foreign to us, we can identify with him very easily… A lot of traditional Mexican music talks about love, loss, betrayal, pain—so in a way, it’s ingrained in us.”

The timeliness of these common themes is not lost on Bastida. These are painful and uncertain times for a lot of Angelenos—a 2013 University of Southern California study showed that one in 10 Angelenos is undocumented, part of a broad array of Angeleno groups and nationalities that feel singled out by the rhetoric and policy of the Trump administration. Bastida is using her art to make statements on this—most notably an upcoming music and film project about the thousands of Haitian refugees who are stranded in Tijuana after having been denied asylum in the U.S.

Los Angeles is also investing in the cultural resistance. Shortly after Trump’s election in November, L.A.’s government signed a memorandum of understanding with the Mexican government declaring 2017 the Year of Mexico in Los Angeles. Existing cultural diplomacy programs offered by the Mexican consulate will be boosted with an eye toward countering the anti-immigrant attitude of the current administration.

On a Friday in early March, at one of these events at the Mexican consulate, the theme is lucha libre—one of Mexico’s signature hybrid cultural products. There are two art exhibits, including stunning images of a burlesque lucha libre show put on in Los Angeles every few months, Lucha VaVOOM. The photographer, Oscar Zagal, says he was invited to show his art without restrictions—female lucha libra fighters with bare breasts adorn the walls. His pictures, says Zagal, aim to rattle and to inspire.

“We are looking for symbols that represent freedom, that represent an alternative. And I think some people are turning to Mexico. Yeah, the Mexican government is probably not a very good example of democracy—we have a very long history of change—but seeing governments like the one we’re seeing now in the U.S. makes us look for alternatives.”

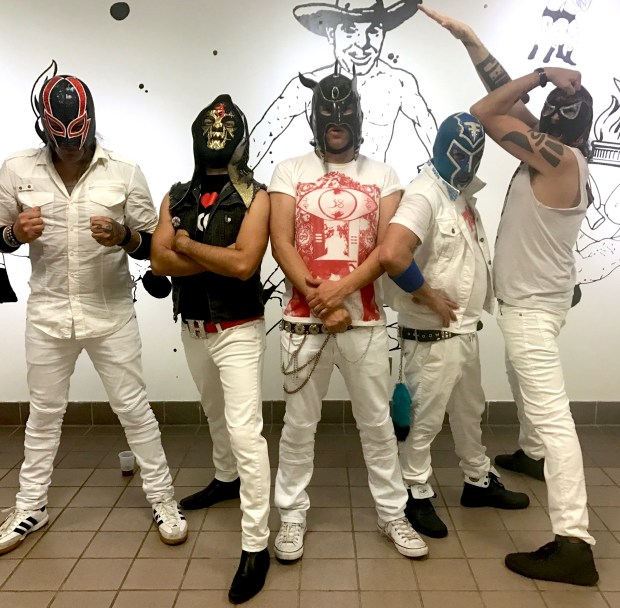

Local vendors have donated tequila and other food and drink. Local cumbia group Conjunto Nueva Ola, which always wears lucha libre masks, manages to turn the crowd (an improbable mix of high-society Hollywood types and the working class) into an impromptu dance party. The dancing takes place in the same spaces where many Mexicans living in L.A. get their passports renewed and, nowadays, take advantage of pro bono legal aid services designed to help them cope with the heightened fear of deportations for the undocumented among them.

“We are focusing on two audiences—one is our own community, so that they feel that the consulate is not just an office where they’re issued their passports or IDs, but also a place where they can enjoy and approach their roots,” says Andres Webster Henestrosa, the consul for educational affairs who oversees the Year of Mexico functions.

“But also we want to get other audiences, other publics, to show them that Mexicans are more than what they think they are. That Mexico is art, that Mexico is culture, that Mexico is an economy, that Mexico has a strong economic sector. There are business people. There are modern people, there are traditional people. Mexico is a very big country, there are many aspects of it. That’s our goal—for those two publics.”

Music is an important part of all this. In June, events will center around rock and its importance in Mexico and here in the U.S.

“Rock ’n’ roll was born here in the United States and emigrated to Mexico. [The Mexicans] developed their own kind, came back to Los Angeles, and transformed it into Chicano groups like Los Lobos and others that became big around here,” says Alina Escarcega, one of the organizers of the Year of Mexico events.

The rock events in June will feature a series of concerts and a photo exhibit by Zagal and artist Fernando Aceves (who famously photographed David Bowie at the Mexican pyramids in Teotihuacan).

Tomas Cookman is founding CEO of Nacional Records, a leading label for alternative Latin music that helped popularized big name Hispanophone acts like Manu Chao, whose song Clandestino has become an homage to the international migrants like those crossing the border at Tijuana and elsewhere.

Cookman, speaking at his small office space in the industrial east of Los Angeles with paintings of lucha libre on the walls, says the dire political environment is adding to the creative urgency of a lot of latin rock. “Music and passion—there’s a direct line between both points. What we’re talking about here is a very passionate message, if you’re talking about disconnecting families and upending lives.”

La Vida Bohème is one of Nacional’s bands—a Venezuelan group with a sizable international following. I spoke to lead singer Henry D’Arthenay by phone from Mexico City, just before the band traveled to the U.S. to perform at South by Southwest in Austin, Texas.

“The United States I knew was the United States of Obama because that was the time I started touring there. The impression I had was a most beautiful one,” said D’Arthenay, “I think North Americans will rise [up against] that idiocy.”

“What I understand about North American culture, at least the culture I like is that it’s a culture that doesn’t make people outcasts,” he added.

Which brings us back to Morrissey, the original outcast musician. The famously reclusive singer (who admittedly has a tendency to step in it when he does talk publicly) recently granted an interview to the Spanish-language culture site sopitas.com. He praised Mexrrissey and their version of “Last of the International Playboys”—Bastida reposted the interview, with heart emojis, on her Facebook wall—and talked about everything from depression to the Rock N Roll Hall of Fame to the “total terror” of the Trump administration and the “ridiculous” wall.

“The United States would be nothing without Mexico,” said Morrissey, undoubtedly causing both sides of the border to fall in love with him all over again.