When I first moved to the city, making the great financial mistake of a master’s degree in creative writing when the last thing a poet needs is a master’s degree, I was living up on East 26th Street in a miserable NYU graduate housing unit dominated by dental students, in a nondescript part of town called Bellevue South for its proximity to the infamous madhouse. I felt painfully out of place, a young poet among aspiring dentists, all jammed in the elevator clutching their grisly, grinning tooth molds. I got romantically depressed, drinking cheap red wine while listening to John Coltrane and working on my Frank O’Hara knockoff poems when I wasn’t cleaning toilets in uptown apartments for a few dollars an hour. On good days, I’d hike downtown with a notebook in my bag, a knife in one pocket and mugger money in the other, not quite breathing until I got below 14th Street, when I crossed that blessed threshold between Nothing and Everything.

One afternoon, I came upon Astor Place, gateway to the East Village, and felt a sense of wide openness. The thieves’ market bustled around an empty parking lot with junk for sale on dirty blankets. St. Mark’s Place looked like a bazaar in Marrakech, a cluttered and inviting souk spiced with incense. A jazz trio played. Punks went in and out, hair stretched high into impressive, neon-colored Mohawks. Dealers whispered the rhythmic incantation, “Smoke, dope, smoke, dope, shroooooms.” It was love at first sight. I had found my home, the place I’d been searching for, and moved in soon after. Much more recently, however, Astor Place has become unrecognizable.

“Undulating.” That was the word that starchitect Charles Gwathmey used for his newest creation, “Sculpture for Living.” A twenty-one-story glass condo tower with a “limited collection of 39 museum-quality loft residences” priced from $1,995,000 to over $6,500,000, it began rising on Astor Place at the dawn of the new millennium. The East Village had never seen anything like it. This “green monster,” as critic Paul Goldberger called it in The New Yorker, looks like a vertical fish tank, humming aquamarine. “It doesn’t belong in the neighborhood,” Goldberger concluded. “By designing a tower with such a self-conscious shimmer, the architect has destroyed the illusion that this neighborhood, which underwent gentrification long ago, is now anything other than a place for the rich.”

Gwathmey’s Sculpture for Living not only undulated, it dwarfed everything around it. Astor Place was no longer the open space I had encountered years before. Completely out of scale with the lower- rising nineteenth-century stone and terra-cotta architecture that surrounded it, the tower seemed to have migrated straight out of the dark caverns of Midtown, hailing the horrifying start of Astor Place’s transformation into a corporate office park that realtors would rename Midtown South. The New York Observer marked the moment in 2004 when they wrote that “the gateway to the once-bohemian and still hardly wealthy East Village” was now “poised to become downtown Manhattan’s next important driver of the luxury real-estate market.” And it was Cooper Union that put the tower there.

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art had been offering a tuition-free college education since its founding in 1859. To do so, the school relied in large part on their real estate holdings, especially the millions in rent and tax monies from the Chrysler Building, built on land owned by the school. But in 2001, running at a deficit, they launched a plan that would put the Gwathmey tower on their parking lot, and then build two more like it, a “wow factor” academic building and a corporate office complex. The plan came with boutique zoning changes. The goal of the rezoning, explained the Times, “was to maximize the amount of usable office space in the new tower” and “to allow commercial development on land restricted by law to educational and philanthropic uses.” In 2002, Bloomberg’s City Planning Commission approved the scheme and added a plan of their own—to demap Astor Place itself, wiping away the historic street and visually joining the condo tower with the corporate tower to come. To no avail, East Villagers fought the plan, arguing that “the large-scale development would turn their eclectic, artistic neighborhood into a sterile business campus.” A decade later, the office tower went up. At 400,000 square feet and skinned in black glass, 51 Astor Place became known to locals as “The Death Star” for its dark and hulking resemblance to Darth Vader’s planet-killing space station. An anonymous satirist started a Twitter feed for the building called @51deathstar, describing itself as “Destroyer of neighborhoods. Unloved. Empty inside. Midtown South.” The imagined voice of the building tweeted snarky messages like, “Hey East Village! Sorry I had to destroy you. My dad made me do it and he’s kind of a dick.”

When I moved to the East Village in 1994—though it had already changed, as any old-schooler from the 1970s and ’80s will attest—the place was still full of poets, queers, and crazies. Young people came mostly to live as outsiders, to read their poems at St. Mark’s Poetry Project and the Nuyorican, shoot pool in the dive bars, and go mad in Tompkins Square Park. I used to run into Allen Ginsberg squeezing the organic fruits at Prana Foods or slurping a bowl of soup at Kiev, the Ukrainian coffee shop where I’d order a buttered bagel and cup of hot water, dipping my own tea bag to save money. (Ginsberg wrote of the place in a 1986 poem: “I’m a fairy with purple wings and white halo / translucent as an onion ring in / the transsexual fluorescent light of Kiev / Restaurant after a hard day’s work.”) In the window of the Cooper Square Diner, I’d see Quentin Crisp, hair tinted purple, silk scarf around his neck. They were already aged, these legends, and would not last much longer. Ginsberg went in 1997 and Crisp followed in 1999, both dead before the decimating changes of the twenty-first century could sweep them away.

I wonder what became of Warhol Van Gogh, the psychotic artist who’d draw your portrait for a dollar. She drew mine while eating falafel on St. Mark’s Place. On bad days, I’d see her raving in the middle of traffic, head freshly shaved from Bellevue, dressed in a pale blue hospital gown. What happened to the other muttering madwoman who walked up and down First Avenue in Chinese laundry slippers, to the man who sat screaming on a milk crate outside my building but always made way for me, or to Marlene Bailey, better known as “Hot Dog,” who drunkenly entertained the sidewalk bums outside Odessa restaurant (the “old” Odessa, site of a thousand late-night omelets and “Disco Fries,” now shuttered)? What happened to Baby Dee, the transgender street artist who wore angel wings while she pedaled a giant tricycle and played the accordion? What happened to performance artist Gene Pool, aka the Can Man, who rode around on a unicycle dressed in a suit made of aluminum cans? He got a write-up in the Times, where the journalist pitied him for trying to get noticed in a town chock-full of eye-catching characters. “There’s just so many people who look so odd and they’re not trying to be noticed,” Pool told the paper. “It’s just their normal getup.” You can’t say that today; the New York character is vanishing fast. (This morning, however, I did see a bewigged drag queen rolling down Second Avenue on a Citi Bike. Hello, polar bear.)

Wherever these people went (Baby Dee left for the Netherlands, Pool’s gone to Chicago), they took with them the distinctive feeling of the place, a feeling of existing on the edge, in a space apart. For several years, when I’d come home from the dull uptown office job I had then, when I crossed 14th Street and veered east, I felt the everyday world lift away like a heavy winter coat shucked off. The crowds fell back. I relaxed, loosened my tie, and slipped into my true skin. I was not the only one. Stepping into the East Village, we saw others like ourselves—poets, oddballs, punks, queers—still a revelation after a lifetime of lonesome singularity. We read their signs and flags, messages broadcast from haircuts and jackets, from slogans on buttons and T-shirts, and we felt not alone. This is a big deal. For some of us, this is everything. Especially at twenty-two years old. But even at forty-five.

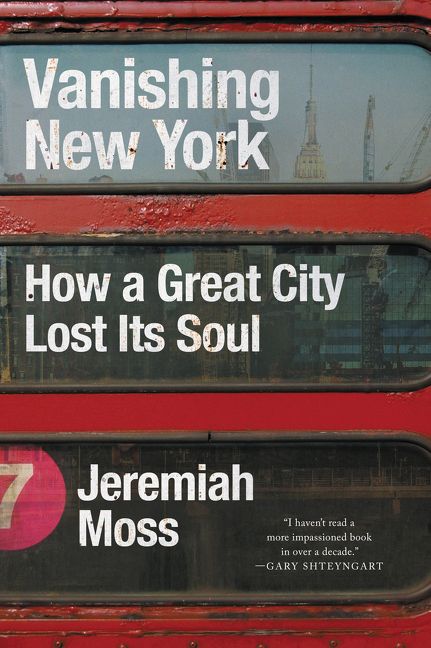

Adapted from the book, Vanishing New York: How a Great City Lost Its Soul. Copyright ©2017 by Jeremiah Moss. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers