Pancho Prieto makes his living collecting escamol—ant larvae—on the high plains of the Mexican state of San Luis Potosí. For the past 20 years, the 57-year-old has anxiously awaited the harvest season, when he can venture into the desert and pilfer eggs from ants’ nests. Sitting with his family around a bonfire, kids and adults alike watch and participate in the cleaning of the escamol while they recount anecdotes from that day’s harvest. The women describe their worry while waiting at home for their husbands and children, watching as ice fell from the sky. None of them had ever seen snow before.

It was March of 2016, and light snowfall had painted the mountains of the Potosí highlands white and silver.

Prieto and his family scavenged about 4 1/2 pounds of ant larvae that day, well below their expectations. The year’s cold weather slowed the ants’ reproductive cycle, so the escamoleros had to begin their harvest three weeks later than usual. Collecting the larvae has become the economic linchpin for entire families in the Potosí highlands, where the climate is fierce and economic opportunities are scarce. By collecting ant larvae, families can earn approximately 8,800 pesos ($502.66) each year. With the previous season’s earnings, Prieto constructed an extra kitchen. This year he will pay for his granddaughter’s quinceañera celebrations.

As with any culinary specialty, the origin of the product matters. The larva of the ant comes from the humblest corners of Mexico, but during the journey from the deserts of San Luis Potosí to Mexico City, the product becomes a luxury good: the caviar of the desert.

The word escamol comes from the indigenous Nahuatl word azcamolli, or azacatlmol, a combination of azatl (ant) and molli (stew). The tradition of eating escamoles is traced to pre-Hispanic times, and Aztec songs, dances, and fables depict feasts featuring the eggs. Several historians mention the larvae as one of the gifts offered on special occasions to Emperor Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, the Aztec emperor from 1503 to 1520. Since then, escamoles have been considered an exclusive dish due to the difficulty of harvesting them.

To collect the larvae, the escamoleros gather at a central escamol collection center in town. There they rent a pickup truck that will take them as close as possible to the mountain in the desert where they can find ants’ nests. Difficult roads eventually force the escamoleros to abandon their vehicle and walk the rest of the way.

They divide into pairs. Teaming up is an important part of the collection process because “you have to work with someone you have a lot of faith in,” says Prieto. Some have worked with the same person for more than a decade. Often you see father-and-son teams.

The pairs begin their trek toward the nests. Each farmer has their own nests, and everyone respects each other’s claims. One person can have three or five nests that they have owned for years. Once they arrive, they begin to capar (castrate) the nests; it’s the term the farmers use to describe the harvesting.

First they wrap their feet with plastic bags and secure them with rubber bands, the only protection they use. With a shovel, one of the escamoleros begins to cautiously scratch loose the top layer of dirt. They have to be extremely cautious so as not to kill the ants or destroy the eggs. Once they begin to uncover the nest, an intense odor emerges; imagine grabbing a bunch of wet soil, squeezing it between your fingers, and then deeply inhaling the bitter, strong smell. This smell, produced by the ant, is known as la pedorrilla, literally, “the farty one.” While the scientific name of the ant is Liometopum apiculatum, the escamoleros refer to the ant by various nicknames, depending on the region in which they live. In this area they call it la hormiga pedorra: “the farty ant.”

The escamolero now inserts his hand into the dirt and pulls out pieces of the nest filled with larvae, which are placed on a piece of metal mesh in a wood frame. While one of the harvesters is doing this, the other begins the cleaning process, shaking the sieve so that pieces of wood, dirt, and insect fall through. What stays on top of the mesh is the ant larvae, easy to distinguish because of its white color and semi-oval shape. Once they have cleaned the larvae, they collect them in a plastic bucket.

After working on a nest, the escamoleros have to delicately refill the nest with dirt, twigs, and pebbles so that the queen ants don’t die and can lay their eggs again next season. A good nest can provide an escamolero with up to 300 grams of larvae per day.

Once the sun begins to set, the farmers return to town. From there they return to their homes, where their spouses and children wait to begin cleaning the larvae collected that day. Whole families sit in circles around a fire as they take the larvae from the plastic buckets and carefully remove pieces of dirt, dead ant, and other insects with their hands. The larvae are valued by weight, so they have to remove any other material for it to be accepted and bought for the best price. At the end sit jars full to the brim with tiny white eggs.

The next day, before leaving to harvest more nests, the escamoleros gather with their buckets of larvae outside the collection center, where local middlemen buy the eggs. At this point they pay about 200 pesos (a little more than $10) per kilo.

For Prieto, being one of the oldest and most respected escamoleros in the town allows him to skip to the front of the line. With his hat and shiny cowboy boots, he proudly measures the buckets he and his son, Martín, have collected. The manager of the center loudly sings out the weight on the scales. The escamoleros congratulate him on a good harvest while he retreats happily, lights a cigarette, and goes to wait in the truck that will take them back to the desert.

The managers of the collection center place the plastic buckets in large refrigerators to be frozen and preserved. The larvae travel vast distances to arrive at markets and fancy restaurants, where they will cost much more than the middlemen paid.

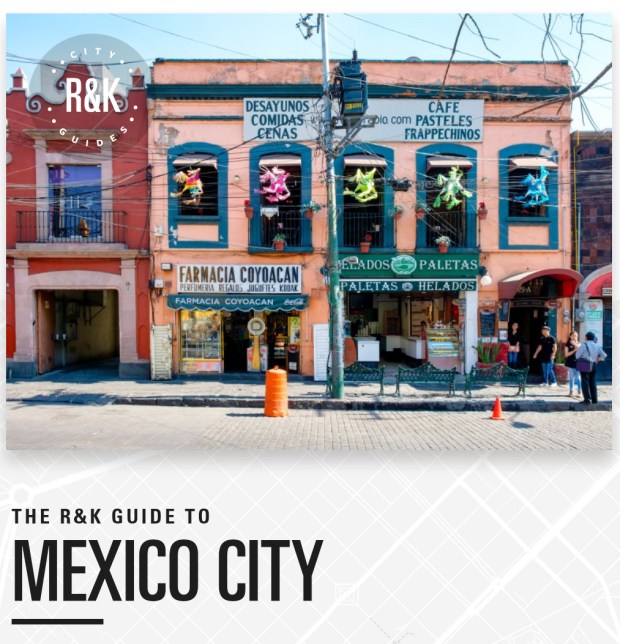

Most will be bound for Mexico City, where national cuisine is having a moment as plucky young chefs undertake the reinvention and rediscovery of the culture’s gastronomy. There’s chef Enrique Olvera, starring in Netflix’s Chef’s Table, sharing his commitment to the reclamation of native ingredients. Pictures of guaje pods emanating black smoke, miniature corncobs, and insects presented on porcelain plates appear in glossy magazines. These are ancestral delicacies for trained palates and thick wallets.

One of the largest purveyors of such delicacies in Mexico City is the Mercado de San Juan, which served as a slave market during the colonial era. Today it’s the place to buy and sell the most exotic products and ingredients: You can find anything from lion meat to crocodile and tarantula—and, of course, ant larvae.

The market is known by kitchen aficionados and culinary professionals for its variety. You can find Asian and European chefs roaming the aisles, chatting amicably with vendors as they smell the fish and examine the vegetables. During the weekends, curious tourists gather in tiny restaurants in the market, wanting to witness the sale of unusual, and even prohibited, meats.

Pedro Hernández, the 55-year-old who now serves as the market’s manager, is one of the most fervent collectors of escamoles, insects, and exotic meats in the region. He has consolidated a local empire that is dedicated to the commercialization and distribution of products native to the Mexican countryside. His relationship with escamoles began during his childhood in the state of Hidalgo; in the state capital Pachuca, his grandmother used to barter the ant larvae for used clothes and something to eat. “I was born surrounded by these ingredients: escamoles, maguey maggots, chiniquiles. I have eaten them since I was born; that is why I hold them dearly and have deep respect for them,” says Hernández. “The escamol is a very powerful ingredient. If you eat it while it’s tender, your mouth becomes numb. Then you feel the power of the little egg.”

Another link in this chain from desert to dining room is Raúl Fernando Valencia Lecona, a 28-year-old lawyer who promotes fair trade initiatives between farmers and restaurateurs in Mexico City. Valencia is part of a new generation who, conscious of the inequality that exists between the country and the city, has dedicated their professional lives to distribution of products that circumvent the smuggling system in which intermediaries take high percentages, leaving the least profits to those who actually collect the escamoles in the fields.

One of Valencia’s clients and allies in the fight to change the inequality between the country and the city is young chef Jorge Vallejo, who co-owns with his wife Alejandra Flores the restaurant Quintonil, a small high-end restaurant in Mexico City’s Polanco neighborhood.

Vallejo is part of a movement among Mexican chefs to integrate local ingredients into their restaurants and to promote fair trade and economic solidarity with the people who are responsible for these products, including escamol. His most popular escamol dish right now is avocado tartare, which features the larvae alongside serrano peppers and other strong flavors. Eager eaters make reservations months in advance for a taste of the delicacy.

But the reality is that small producers like the Prieto family are not often lucky enough to be aware of people like Valencia or Vallejo. In the desert of Potosí, the idea that someone would pay more than $20 for a plate of escamol seems like a bad joke. For now, the Prietos are focused on the snowfall and the hope that the weather will be better next winter.

Originally published on Roads & Kingdoms on Apr 16, 2017.