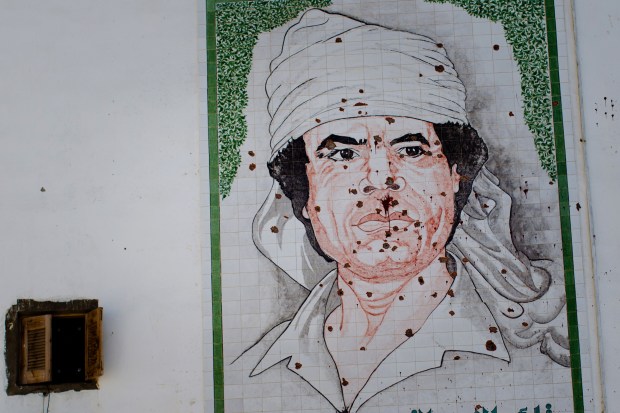

Few countries have been shaped so much and for so long in the image of one man as Libya. In 1969, Moammar Gadhafi, then a young army officer, came to power after a military coup. In 2011, he was ousted in a popular uprising that drew in a NATO-led intervention mandated by the U.N. The man who styled himself as Brother Leader met a bloody demise at the hands of rebel forces in October of that year. For much of the 42 years between his rise and fall, his Libya was a pariah state, hobbled by sanctions and isolated. Foreign academics and journalists were not welcome, and little was known about the country and its people. For much of the world, Libya was Gadhafi, and Gadhafi was Libya, and that was how the Brother Leader preferred it.

When his regime came crashing down in 2011, Libya’s transition from dictatorship to democracy promised to be anything but easy. He was no ordinary autocrat, and his idiosyncratic and often brutal experiment in governance hinged on layers of patronage, the manipulation of tribal dynamics and ad hoc edicts that were sometimes reversed abruptly, according to his whims. Nevertheless, in the immediate aftermath of Gadhafi’s overthrow, many Libyans dreamed of their country becoming a new Dubai on the Mediterranean, while others wanted to see it emerge as the Switzerland of North Africa.

At the time, on paper, Libya could appear deceptively straightforward to the casual observer: a predominantly Sunni Muslim population of just 6 million without the sectarian and ethnic divisions that plagued Syria and Iraq or the literacy challenges that held back neighboring Egypt. Most Libyans are urbanized, and two-thirds are under 30 years old. Their country is home to Africa’s largest oil reserves. Some believed Libya had the potential to become a success story of the Arab Spring.

It was not to be. With Gadhafi gone for seven years now, Libya is deeply divided. Rival governments, rival institutions, rival warlords and a multitude of militias in between make the prospect of Dubai on the Med look very remote. Eyeing opportunity in the years-long political and security vacuum is the so-called Islamic State. Largely a foreign-dominated movement in Libya, the group was dislodged from what had become its stronghold in Sirte—coincidentally, Gadhafi’s hometown—in 2016. The Libyan affiliate of the Islamic State, though now weakened and scattered, remains a threat, as recent attacks on the National Oil Corp. and the national election commission in the capital, Tripoli, have shown.

Also, taking advantage of Libya’s chaos and its porous borders are smugglers of many varieties, particularly those who traffic in humans. Migrant smuggling networks that existed under Gadhafi have expanded since his fall. The business of spiriting people through Libya to Europe has become highly lucrative and multinational, linking Libyan organized crime with counterparts elsewhere in Africa. Some migrants are subjected to forced labor to pay for their passage across the Mediterranean. Others find themselves held in atrocious conditions in detention centers ostensibly run by forces aligned with the internationally recognized government in Tripoli. Ordinary Libyans are increasingly resentful of the fact that their country has become such a hub for human traffickers and a transit point for migrants in the region desperate to get to Europe. In a sign of Libya’s unspooling, a growing number of Libyans—particularly from the disillusioned younger generation—are also chancing their luck on the smugglers’ boats. One was MC Swat, a well-known rapper whose star rose during the 2011 uprising. His later work, which dissected the ills of post-Gadhafi Libya, brought him death threats from various militant groups, forcing him to flee.

Activists and journalists face intimidation and harassment in Libya, usually from the patchwork of armed groups that hold sway across the country. In the east, they fall under the command of Khalifa Haftar, a controversial septuagenarian general who was by Gadhafi’s side in 1969 but later defected and today dreams of military rule. He argues that Libya is not ready for democracy and presents himself as anti-Islamist, even if hardline Salafists are key to his fighting forces. In Tripoli, the U.N.-backed government opposed by Haftar partly relies on militias consisting of similarly minded Salafists for its security. Caught in between are ordinary Libyans who wonder if they will ever be rid of the militia culture—some of it regionally flavored, some of it tribal, some of it ideological—that emerged from the armed brigades formed during the 2011 uprising.

Libyans are proud of their country, a land on which once walked Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Ottomans and later Italian colonizers. Many are fond of quoting Aristotle’s Historia Animalium—“Libya always brings forth something new”—even though the ancient Greeks used the name to refer to wider northwestern Africa. They and the Romans who followed left behind some of the finest classical ruins in existence, including Leptis Magna (the birthplace of Septimius Severus, the first Roman emperor born in Africa) in western Libya and Cyrene to the east. Add to that one of the longest coastlines in the Mediterranean, most of which is unspoiled, and what are considered some of the most beautiful stretches of the Sahara, and it’s no wonder some Libyans, when thinking about how to diversify their oil-dependent economy, believe tourism might be part of the solution.

The collapse of the Gadhafi regime in 2011 exposed layers of dysfunction in the eccentric version of the classic rentier state he crafted over four decades. Gadhafi’s Green Book—an odd mix of aphorisms he had translated into dozens of languages—provided the philosophical underpinning for what he called his Jamahiriya, an Arabic neologism which can be translated as “state of the masses.”

The Brother Leader’s legacies include not only an economy almost completely reliant on hydrocarbons but also one of the largest public payrolls in the world. Reforming that remains one key challenge. How to include Gadhafi’s former supporters and those who were part of the machinery of his dictatorship—including his son and once heir apparent, Saif al-Islam—in the new Libya is another. There is a growing consensus that former regime officials who do not have blood on their hands must be brought in from the cold if the country is to eventually stabilize.

When Libya, at war with itself but also at the mercy of numerous external meddlers, might ever find peace and stability is another question. Every transitional government since 2011—each one more wobbly than the last—has included a minister for tourism. Depending on who you ask in the country, that is either an act of admirable optimism or hopeless wishful thinking.