It first hits you as you enter the station: a whiff of the damp, mildewed walls. Then there’s the sound of British-era trains, groaning with old age, some creaking to a halt and some lumbering up the rusty tracks with a rhythmic tha-chunk. Yangon Central Railway Station is filled with sensory pleasures.

There’s something comforting in knowing these beaten crayon-colored wooden trains have predestined stops: They can only go where they’ve been a million times. From Yangon Central, you can buy a ticket to obscure river-delta cities, such as Bago, for less than $10. There you may find temple fairs where agile boys swing from ferris wheels to throw them into motion: a local solution where electricity is unreliable. Or you might stop in a town called Pyay, where you can see Shwesandaw Paya, a pagoda said to contain some of Buddha’s hair.

But for me, the station is an attraction unto itself. Grand but weathered, Yangon Central is the largest train hub in all of Myanmar. And it’s among the best people-watching spots in Southeast Asia.

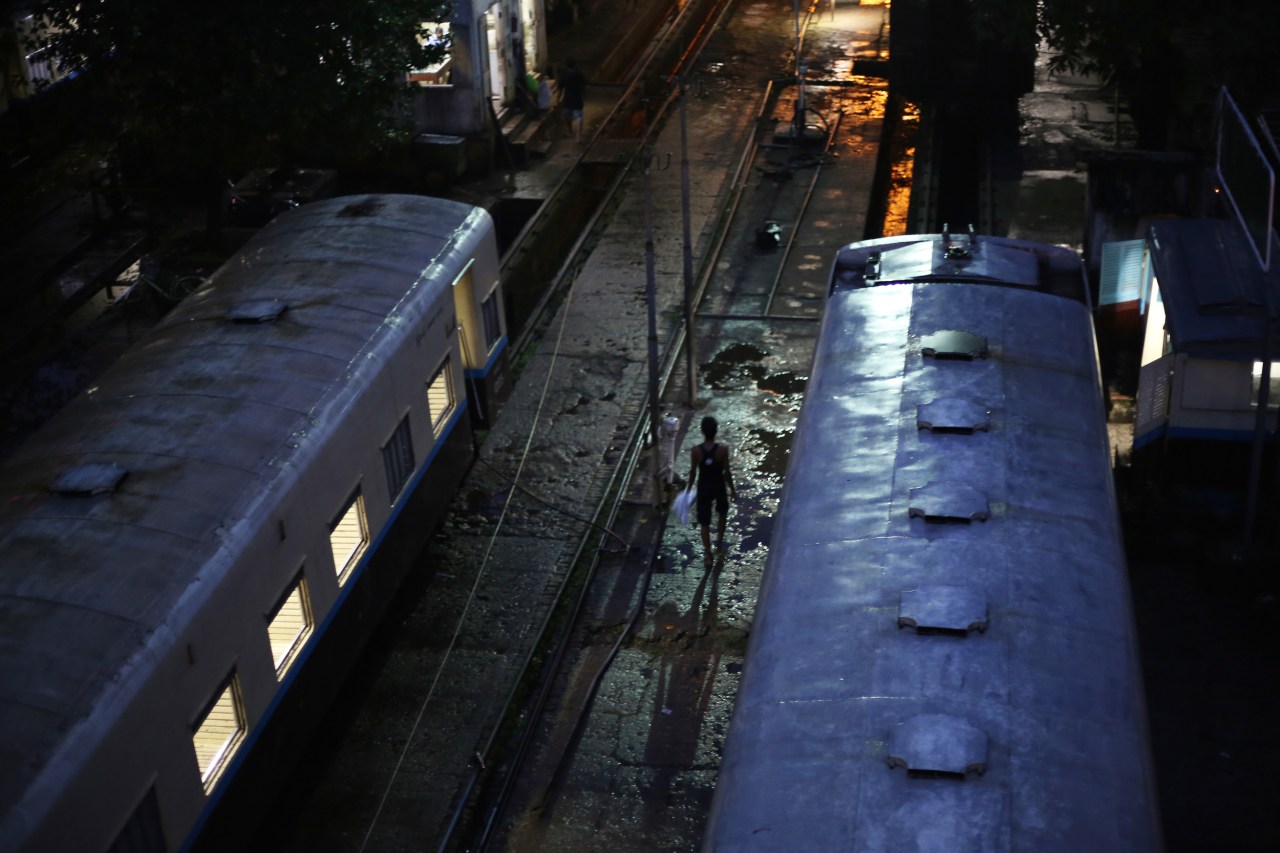

The trains come and go, of course, but the station is home to a community of people who live within its walls.

Some are compelled to live there by necessity: The station has running water, which is still a prized commodity in Yangon. Another perk: low crime, thanks to the vigilant station-dwelling community. Moms can plop their babies on the floor and run errands without fear. Someone will keep an eye on the child.

This is the second incarnation of the station. It was originally built in 1877 by British colonialists at the height of their reign. Yangon, then the country’s capital, called Rangoon, was a blank slate for the empire after the Anglo-Burmese Wars destroyed most of the town some 25 years earlier. Back then the railway only stretched from Yangon to Pyay (then known as Prome) and amounted to just 163 miles of track. Today the network has more than 3,000 miles of rail.

The inhabitants of Yangon Central Railway Station survive by selling cheap snacks to travelers. This is a visual exploration of the station and its people: some of them dashing to remote destinations, others clinging to the station for survival.

Originally published on Roads & Kingdoms on Sept. 29, 2015.