Linda Pappas Funsch is the author of Oman Reborn: Balancing Tradition and Modernization, and a specialist in modern Middle Eastern and Islamic studies. She spoke with Explore Parts Unknown to share her expertise on the culture of Oman. With the enthusiasm of a born teacher, Funsch explains what makes modern Oman unique, the relationship between Omanis and the Sultan, and where the country is headed economically and culturally in the 21st century.

When I was serving with the Ford Foundation in Beirut, I visited Oman in 1974. We were embarking on a joint research project with the government of Oman and the UNICEF office in the region, a project that was designed to assist women and children with health and literacy issues. I served on an international team, and I was dramatically impressed by what I saw. Having lived in Lebanon and Egypt and traveled around various regions of the Levant, I thought Oman in 1974 was like the other side of the moon. You have to appreciate that in 1970 Oman had only six miles of paved road. There were only three primary schools, which enrolled less than 1,000 students—all boys—and there was no national infrastructure. It was a very, very different sort of place. Sultan Qaboos at that time had the foresight to ask international agencies to help him prioritize a development plan, which is part of the reason I was there. I was struck with the raw beauty of the place and captivated particularly by the warmth of the Omani people.

The path to modernization

Thirty-two years later, I returned to the Sultanate and was blown away. Here was a country that had been transformed. In those earlier years, it was a country almost frozen in time. Now it was clearly on the move—much of it was unrecognizable in terms of infrastructure. It had developed and modernized dramatically. I saw an intricate system of roads, schools, hospitals, hotels, and upscale retail establishments where few if any had existed before. What struck me most was that while it had modernized, it was still distinctively Oman, which is what inspired me to write my book.

Its path to modernization was and continues to be guided by its rich history and its unique culture. It has modernized, but it has not Westernized blindly. It has been selective in its modernization. It has employed from the West—technology and so forth—that which is most appropriate to its needs. But it is still very much Oman in every way, which distinguishes it from many of its neighbors.

Omanis have a sense of their history, and, as a friend of mine who is a former U.S. ambassador, has said, “They are comfortable in their own skins. They have a history, they know who they have been, they know who they are, and they know where they’re going.” I thought that narrative of blending tradition and modernization was very interesting. I’ve visited many of the neighbor countries where that paradigm has not been followed. In addition, I wanted to tell the story of Oman because it is very much a good-news story, and that’s unique, especially in the region.

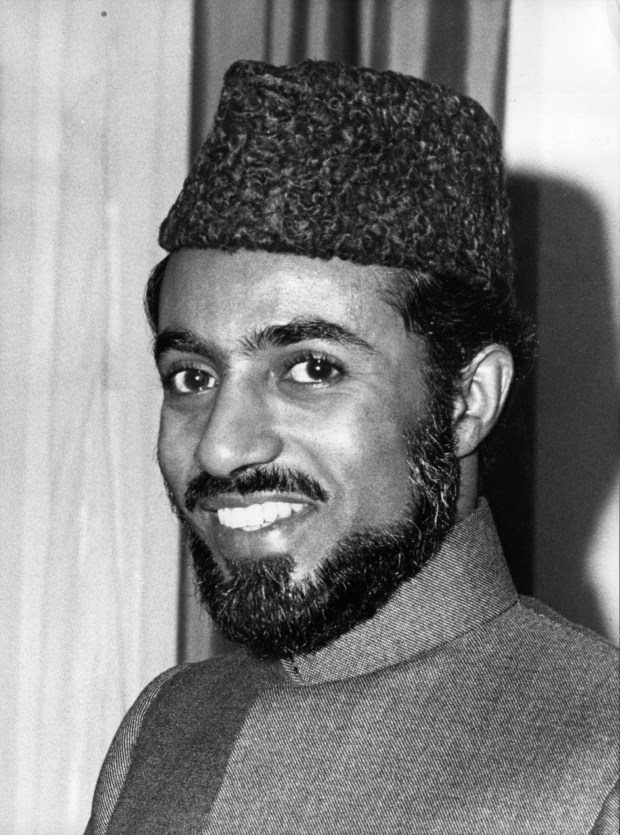

I should like to point out that in a region of all-too-familiar wanton violence and sectarian intolerance, Oman is stable, optimistic, and friendly with all of its neighbors on both sides of the Persian Gulf. It is resolute in its policy of noninterference in the internal affairs of other nations. Oman is a generous country but does not send its military to fight in other lands. It insists on its own independence and very much appreciates others reciprocating. It is a country that has developed its democratic institutions in stages but always with a keen eye toward its history and culture. It extends rights and privileges equally to both male and female citizens. Its leader, Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said, is one of the longest-ruling heads of state in the world—now almost 47 years—and he is credited to a large extent with the transformation of the country into a successful, forward-looking 21st-century state in less than 50 years.

A rich, seafaring history

Oman encompasses part of the Empty Quarter of the Arabian Desert, but there are also fertile areas, large areas that we would call oases, and glorious mountain ranges. In my estimation, what is most important about Oman’s geography is that it has over 1,100 miles of coastline. When Westerners think about Middle Eastern states or “Arabia,” writ large, they don’t typically think of the maritime element of these countries. But Oman is above all a maritime power. In my opinion, this is what makes it unique.

There are records of Omani traders in China as early as the ninth century. Omanis have traversed the Indian Ocean. They founded colonies in East Africa—Zanzibar and Tanzania were Omani colonies—and Oman held sway in parts of South Asia, which was of major importance in the 19th century. So it was a colonial power, it was a trading power, a commercial power. Why is this important? Because it informed the Omanis’ outlook.

In contrast to many of its neighbors—and I say this advisedly—Omanis are a cosmopolitan people because of their history as a maritime power. They have been in contact with people of every race, every culture, and every ethnic background. This contact has resulted in a people who value intercultural dialogue, and it has made them an open-minded people. They are not pedantic in their interactions with other countries. Also understand that in Oman, while there are people of the Sunni and Shiite tradition, there is also a third sect of Islam called the Ibadi sect. So you have three Muslim narratives coexisting harmoniously in this country, but you also have a Sultan granting Christians land on which to build their churches, as he does Hindus to build their temples. Why do I call Oman a good-news story? This all sounds pretty damn compelling to me, don’t you think?

The role of the Sultan

Sultan Qaboos is the absolute ruler, but he does not rule absolutely. When he came to power, there were no governmental institutions. All rules came from the palace. Within 47 years, Oman has developed a constitution and two houses of Parliament; its governmental structure resembles the English parliamentary system. Those two houses of Parliament advise very strongly; they are very important mechanisms toward democratization. They include people from all over the country, both male and female, of all occupations. What has transpired in recent years is great political participation.

Parliament has become a more meaningful instrument of governing. The constitution is called the Basic Law. It was first set to paper in the 1990s and then amended in 2011, granting even more power to the lower house of Parliament. These institutions are evolving over time. Yes, Sultan Qaboos is the absolute ruler, but he is by no means dictatorial. He is a very wise, very learned, very educated, and very cultured man. I spend quite a lot of time in my book describing not only his background, which is quite fascinating, but also his style of leadership. He is a visionary in many, many ways, and he is truly a Renaissance man. Here is a man who received his military training at Sandhurst, who served in the British army for a spell, who received an education in India when there were virtually no schools above primary level in Oman. He is a man with a foot in both East and West.

I had the great honor in 2011 to be invited to the opening of the Royal Opera House Muscat, where Plácido Domingo led an Italian orchestra in a rendition of Puccini’s Turandot. It was the most magnificent event that I have ever attended. The Royal Opera House Muscat in fact is representative of what Oman has become. Plays, ballets, theater, and artists from all over the world have performed here. When I left Oman in February, I went to the Opera House on my last evening to see a production of West Side Story. So this kind of gives you an idea of a country that is thoroughly modern but also thoroughly traditional. And—it works. I find it a very inspiring tale.

The Omani Renaissance

They call this transformation the Omani Renaissance, and Sultan Qaboos has been the essence of the Renaissance. He has been the architect. He has united the citizens in a common cause. I have lived in parts of the world where you see photos and portraits of the leaders everywhere, but that’s usually something that is forced by the government. Not in Oman.

The most stunning example of the love that citizens have for Sultan Qaboos is from March of last year. After an eight-month absence in Germany, where he was undergoing treatment for an undisclosed medical condition, the Sultan returned to Oman. People were obviously extremely concerned and missing him very much. One day, lo and behold, he stepped off a plane in Muscat. The entire country broke out in a spontaneous heartfelt expression of joy and celebration, and this is rural, urban, young, old, rich, and poor. Omanis hold him in such high regard, and it is genuine. Yes, there are certainly detractors, but by and large he is beloved of his people and respected throughout the region and the world.

The question of succession

His Majesty the Sultan has no children. The Basic Law stipulates that the Sultan of Oman will, at least for this point in time, always be a male of the royal family line, of a particular branch of the el Said tribe, and born of an Omani mother and an Omani father. The royal family council meets, and they have the opportunity to agree on a candidate for what is called the Sultan of the Country.

The succession issue is outlined in the 2011 amended version of the Basic Law. According to the amended Basic Law, the royal family council has the first opportunity to choose a successor. That group meets within three days of what they call euphemistically the “throne falling vacant.” If they are unable to agree on a candidate, the defense council, together with the chairperson of the two houses of Parliament and the Supreme Court as well as two other deputies, announces the person designated by His Majesty the Sultan in a letter he has prepared, naming his successor.

Governance in Arab societies is historically based on consultation and consensus. Even though there is a leader, decisions are very rarely reached on the basis of one person’s thoughts and inclinations. So the leader gives the royal council an opportunity to decide on the basis of consultation. If they are unable to reach a consensus, then this other council opens the envelope, and they see who His Majesty has designated the most worthy to hold the position.

Now here’s another thing. I talk about this in my book also, because everybody is obsessed, saying, “Oh my gosh no one’s ever gonna be able to fill his shoes.” Of course he will be a legend forever, but one Omani said this to me: “Look, everybody is so concerned that the country is going to fall apart when His Majesty is no longer on the throne, but he was out of the country for eight months, and we went about our business very well, thank you very much. Isn’t that a reflection of the institutions that have been developed over now 47 years? We have become to a large extent a self-governing country.”

Omanization

In terms of the economy, the Omanis have had a plan in place for many years that they call “Omanization.” It is a program intended to do two things: diversify the economy increasingly away from its dependence on hydrocarbon production and employ more Omanis into the workforce to lessen their dependence on expatriates.

When the country began to modernize in the ’70s and ’80s, it needed expatriates because there were very few native-born Omanis who were equipped to handle the challenges of modernizing the country. So the expatriate labor force, skilled and unskilled, is very important. It has been throughout the region, though Oman’s has never been as large as it is in countries like the United Arab Emirates, where 70 to 80 percent of the workforce is expatriate. In Oman it hovers somewhere between 40 and 45 percent. If the second aspect of Omanization is to lessen the dependence of the economy on expatriates and put more Omanis to work again in an economy that is more diverse, then this is where I think Oman’s future is rather compelling and optimistic.

What’s next?

Due to its geography and maritime history, Oman is becoming an increasingly important center for trade and commerce. It has constructed new state-of-the-art port facilities along its coasts, it has constructed new airports and expanded old ones, and there is a planned national railway system. There is a brand-new port and city built around it in Duqm, in the central part of the coastline. Trade and commerce are, to a large extent, where I think the country’s future lies.

An even larger part of Oman’s future lies in cultural tourism and in ecotourism. The country has many UNESCO World Heritage sites, a variety of stunning landscapes and breathtaking vistas, swimming, snorkeling, cave exploring, and mountain climbing. In terms of cultural tourism, they say that Oman is the “land of a thousand forts and castles.” There are major museums, the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque, other mosques of note, and of course the Al Alam Palace. It’s a compelling tourist destination. So much of the country—and its history—is not what folks think of when they consider the Middle East, which is why I very much enjoy telling the story of Oman. It destroys stereotypes.