Over the last 15 years, Paraguay’s landscape and economy have undergone drastic changes. Production of genetically modified soybean has bolstered the landlocked country’s coffers to make it one of the fastest growing economies in Latin America. As of 2018, Paraguay is the sixth-largest producer of soy in the world—behind the United States, Brazil, Argentina, China, and India—with 95 percent of its production used as feed for livestock.

Soybean plantations are mostly in eastern Paraguay, and agribusiness companies are steadily spreading to drier, western regions. This rapid growth has created a gaping wealth disparity among the country’s population. Agribusiness elites have grown richer than ever, making up the 2.6 percent of the population who hold 85.5 percent of Paraguay’s land. They live in the country’s capital, Asunción, and belong to exclusive organizations, like Club Centenario, that provide golf courses and swimming pools and host glitzy social events like debutante balls for their daughters.

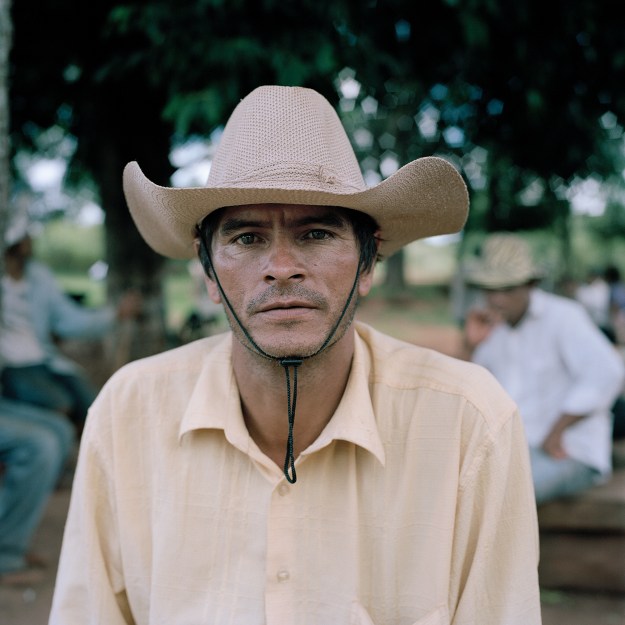

The price of this luxurious lifestyle rests on the backs of Paraguay’s rural communities, which Jordi Ruiz Cirera has been documenting since 2013. He described the dynamic between the ultrarich and the campesinos—small, self-sufficient farmers—as “two worlds living in the same area but never interacting.”

With such a vast gulf between them, the wealthy elite can easily mistreat impoverished campesinos. Some 9,000 rural families are displaced each year to make way for the soy frontier. Farmers and rural dwellers face major health risks from herbicides and pesticides necessary to grow this strain of soybean. This has caused unrest among rural populations.

Cirera documented protests by the campesinos against fumigations that they believe are negatively affecting their health. These demonstrations have been met with violence from the police, culminating most notoriously in the Curuguaty massacre, which left six policemen and 11 campesinos dead.

A drought in Argentina has pushed Paraguay to exceed its neighbor in soybean exports. Paraguay now provides 3.0 percent of global supply, which still leaves it trailing the world’s top two soy exporters, Brazil and the U.S. With the Paraguayan government hoping to double production by 2028, there is no end in sight to the conflict between the campesinos and the government and landowning elite.