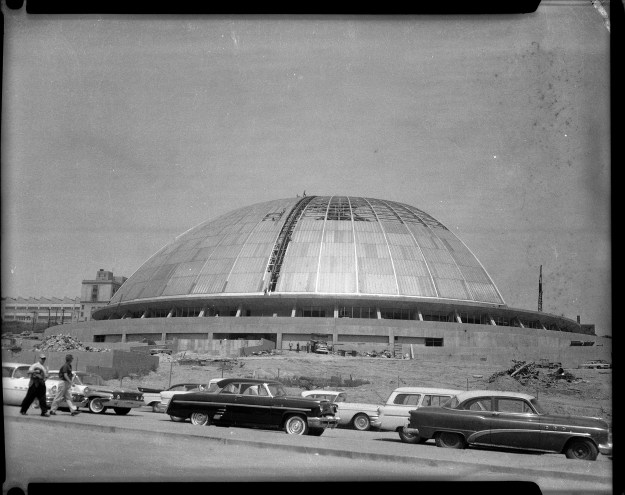

James Brown. Michael Jackson. Stevie Wonder. Back then, when Sala Udin wanted to see the big names play Pittsburgh after they released a new record or eight-track or cassette, he knew they’d play the Civic Arena. The dividing line between Downtown and the historically African-American Hill District, the bubble-shaped arena boasted a retractable roof that enhanced 17,000 concertgoers’ experience with a night-sky canopy. But for Udin, the concerts were always bittersweet

You went to the arena, but with mixed feelings. You had to push those memories of your crushed childhood to the back of your mind. You try to enjoy the show, but then, as you’re leaving, you look back over your shoulder at this flattened space, at this cement parking lot, and you remember the good times but you also feel that pain.

That “flattened space,” that parking lot, had once been Udin’s home.

Brown, Jackson, and Wonder played on the same hallowed ground where Eckstein, Gillespie, and Horne had bopped and crooned decades earlier, back when the Hill served as a second rendition of the Harlem Renaissance. But those artists played Hill hot spots such as the New Granada Theater, Crawford Grill, and Savoy Ballroom long before the Civic Arena opened in 1961. During the first half of the 1900s, the Hill had welcomed newly arrived steelworkers—European immigrants and then African-Americans fleeing the Jim Crow South. A dense grid of streets and alleys housed tightknit families and what became a center of black cultural life.

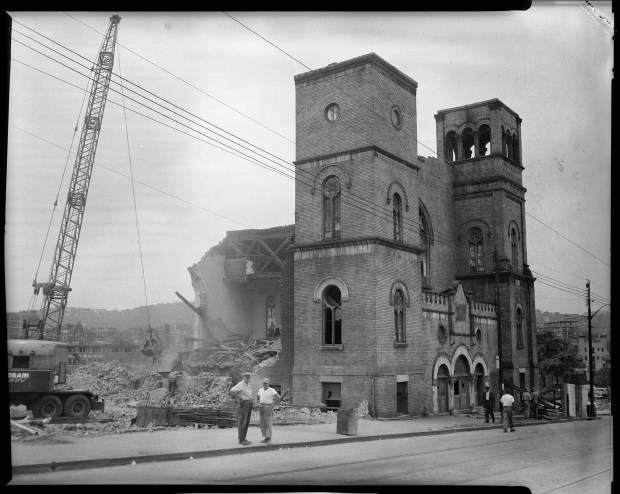

But then came “urban renewal” in the 1950s: the government’s plan to “revitalize” a community by razing portions of it. The Civic Arena and its parking lot displaced 8,000 residents and more than 400 businesses from the Lower Hill, disfiguring a lively community while reinforcing barriers between neighborhoods and races. As in cities across the country, the Hill’s lancing led to a trauma that research psychiatrist Dr. Mindy Thompson Fullilove has labeled “root shock.” It’s the destruction of one’s “emotional ecosystem.” At the community level, it’s the result of redevelopment that “ruptures bonds, dispersing people to all the directions of the compass.”

Udin felt that trauma. When he was 10, his family was forced to leave their home on Fullerton Street in the heart of the Lower Hill to make way for the Civic Arena parking lot. Sixty years later, Udin still feels the root shock, as do many Pittsburghers. And clashes over that land continue even now.

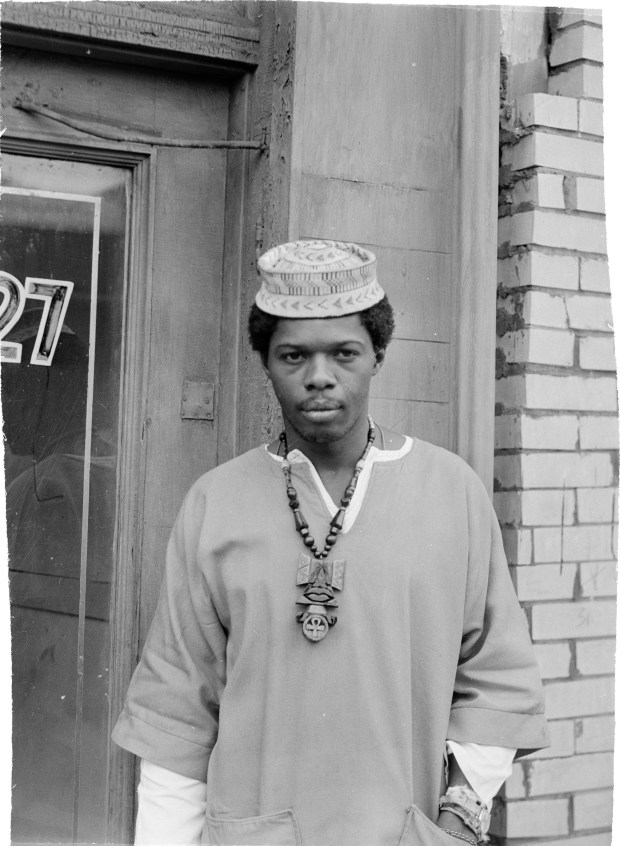

In 1943, Udin was born Samuel Wesley Howze, though he later embraced the name of an African king and scholar. He lived in a three-bedroom apartment above Billy’s, a grocery at the cobblestoned intersection of Fullerton and Epiphany, one block from Wylie Avenue, the heart of the Hill. There Udin’s mother and father raised 12 children and three grandchildren. His father’s work as an industrial laundry presser provided just enough for them to get by. In that old building windowpanes were gusty. Udin knew to hang by the radiator if he wanted to stay warm.

During summer days, Udin played stickball in the street—sometimes as the center fielder, where he’d double as the monitor for oncoming cars. Then, as the streetlights flickered on, Udin and his siblings rumbled up the apartment stairs, grabbed their pillows, and lined the windows to watch the parade of nightlifers walk up and down Fullerton, strutting to the clubs in their ritzy suits and dresses.

Neighbors were like family to Udin. He knew and respected the community’s adults. He rarely heard about crime. And he felt safe. Though Udin’s family didn’t have much, he didn’t consider himself poor.

Then rumors starting seeping into neighborly conversations, on street corners and at church: They say everybody has to move … City’s going to tear down the whole neighborhood … Have to go to new schools … Don’t know why or where…

When Udin asked his parents about these rumors one too many times, he was sent to his bedroom. Looking back now, he understands: My mother and father felt powerless. They felt embarrassed.

Residents knew the rumors couldn’t be far off the mark. A Pittsburgh councilman had written an article noting that 90 percent of the Hill’s buildings were substandard. Therefore there would be “no social loss” in this “disorganized” neighborhood if those buildings “were all destroyed.”

So one day in 1953, Udin’s dad came driving up Fullerton in a truck. Friends helped empty out their rented apartment, and Udin found himself riding a mile or so in his family’s huge burgundy Plymouth to their new home, a public housing complex called Bedford Dwellings.

Here everything shined—the floors, the stove, the sink, the fridge. Even an ice maker. And here, where rent and utilities were subsidized, Udin’s father didn’t follow him around, flipping off the light switches whenever he left a room. Udin had never seen anything quite like this place.

But before too long, a deeper poverty settled into the Hill. Drugs took hold of aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters, not just the hustlers. Manufacturing jobs dried up, and men weren’t heading to work each morning like they did when Udin was young. Having left Little Harlem, Udin and his friends in public housing now joked about living in the City of Red Bricks.

Then in 1961 the arena opened, named for the Pittsburgh Civic Light Opera, though the CLO would leave the arena just a few years later, following complaints of poor acoustics. The arena began hosting circuses, boxing matches, political rallies, music performances, and sporting events. In 1967 that space where Udin once played stickball became home to professional hockey players’ slap shots. One of the National Hockey League’s newest expansion teams, the Pittsburgh Penguins, became the primary tenant in what had come to be known as “the Igloo.”

Udin spent his early-adult years gathering a lifetime of experiences, eventually chronicled by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: from an internship in a Harlem funeral home and playing lead roles in plays written by his Pulitzer Prize–winning childhood friend, August Wilson, to attending Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s march on the National Mall and nearly getting killed as a civil rights activist in Mississippi. There was even a stint in federal prison, after a Kentucky State Trooper found an unloaded gun and a jug of moonshine in his car. (President Barack Obama later pardoned Udin for the crime.) He also married and had children.

Udin repeatedly returned to the Hill. In the 1960s activists drew a line in the urban-renewal sand at Crawford Street, overlooking the Civic Arena. They proclaimed that no more land would be taken from the Hill District. The Freedom Corner memorial, where most of Pittsburgh’s civil rights marches began, marks this spot. As early as the 1940s, residents had been flexing political muscle through the NAACP and other organizations, picketing segregated public facilities and department stores that were refusing to hire blacks or even allow them to try on clothes. That work continued.

But at Bedford Dwellings and throughout the Hill, poverty, drugs, and joblessness took their toll. Families couldn’t rely on the sense of community that had defined Udin’s childhood. People were isolated and hurting. Community trust had been weakened.

“We didn’t know what impact the amputation of the lower half of our body [the Lower Hill] would have on the rest of our body,” Udin later told Dr. Fullilove for her book, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It.

“The rest of [our] body is really ill because of that amputation … a broken culture, broken values, and a broken psyche.”

That illness and sense of fragmentation only grew worse. When Dr. King was assassinated in 1968, riots erupted and people started looting. Hundreds of fires were set in the Hill, destroying numerous businesses—including many owned by whites—that would never return.

We’d found some hope in the father of love and nonviolence. But he became the victim of hate and violence, Udin later reflected.

The bottom fell out of the hope.

Meanwhile, renovations at the Civic Arena enabled seating capacity to grow over the years. The arena attracted stars, from Elvis Presley to Frank Sinatra, as well as professional wrestling, U.S. figure-skating championships, and the country’s first high school basketball all-star game, among thousands of other events. Mellon Financial spent $18 million to dub the dome Mellon Arena for a decade.

Remaining involved in politics and community organizing over the years, Udin was elected city councilman for his neighborhood’s district in 1995, an office he held for 10 years. Proposals for further developing the area surrounding the arena came across Udin’s desk, but he opposed them. He would not support any development that didn’t directly benefit Hill District residents and represent a memory of what used to be there.

Some may have thought him overly nostalgic, a man in his 50s wishing for the good old days.

No, we know we can’t re-create the old Hill District, he’d tell them. But this is our historic home. Any project here has to be something that we are involved in and that we benefit from.

Eventually, the arena itself became a target of redevelopment. The Penguins had won two championships, while the Igloo had begun to feel substandard. The team wanted a new home and threatened to leave.

After years of negotiations, a new arena was constructed on adjacent land, funded by the state, Rivers Casino, and the Penguins. Residents fought the Penguins’ proposal to build a revenue-generating casino in the Lower Hill, right next to their homes. They won, and the casino was instead located on the North Shore.

By 2007 the Penguins had gained development rights to the 28 acres comprising the old arena and that big parking lot, while ownership of the land remained with the city and county. A community group, the One Hill Coalition, negotiated a community-benefits agreement (CBA), the first ever in this region. It established a job center, gave local residents the first shot at jobs connected to building the Penguins’ new arena, and led to the crafting of a neighborhood master plan. The city and the Penguins were each required to chip in $1 million toward a new grocery store, which the Hill hadn’t had in decades. In 2013 a Shop ‘N Save opened in the center of the Hill District.

But this didn’t determine what would become of the arena and happen next in the Lower Hill. Some Pittsburghers wanted to protect the old Civic Arena with a historic-building designation, but their efforts failed. The arena came down. Most Hill District residents were happy to see it go.

The Penguins’ organization has committed to building in its place housing, offices, and retail. But final designs for the space remain uncertain, and it’s been slow going; the Penguins have missed development deadlines, triggering penalties. However, the Sports & Exhibition Authority has designed a pedestrian park to span the highway separating the Hill from Downtown. On a wall surrounding the park’s performance stage, a panel would depict important African-American figures.

Now Udin, 74, finds himself on the board of the Sports & Exhibition Authority, which controls the land the Penguins are required to develop—land that’s among the most valuable acreages in western Pennsylvania. The same land where he grew up.

It’s tempting to forget the root shock that so many Pittsburghers still feel and that Udin recalls when he drives by the new arena and the area that remains a parking lot: Now suburbanites come in to have a good time watching the Penguins. They don’t live here. They just play here. They don’t know the pain that this playground caused.

Still, he’s proud that Pittsburgh’s African-American community has made progress.

We don’t have enough political and economic influence to be owners and builders of the site, but we do have enough political influence and consciousness to make sure we influence the direction of the site’s development.

One sign of that influence: A year ago Udin stood with government officials at a “ribbon-joining” ceremony that marked the reestablishment of two tree-lined streets running back into the Lower Hill, along with renovated sewer and electrical lines and streetlights. The project re-extended Wylie Avenue a few more blocks toward Downtown. And the name of the other street?

Fullerton.