Your reading list for Singapore

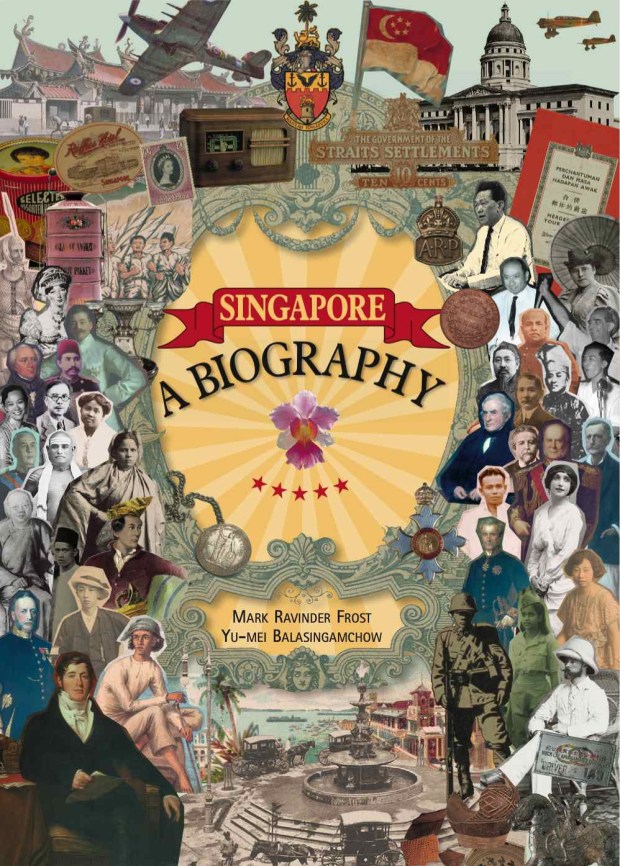

- Singapore: A Biography by Mark Ravinder Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow

If you want an accessible and engaging read to educate yourself on Singapore’s history, this is the book for you. The authors draw on old archives, oral histories and even modern broadcasts, weaving them into a tapestry that traces the journey of the island that we now know as the city-state of Singapore.

- Living with Myths in Singapore, edited by Loh Kah Seng, Thum Ping Tjin and Jack Meng-Tat Chia

Meritocracy, multiculturalism, a linear trajectory from “Third World to First”; these are some of the stories that Singaporeans have been told, and continue to tell ourselves. This book, based on a series of talks and discussions held in 2014–2015, brings together critical and engaging perspectives on these national myths and proposes different ways of seeing Singapore.

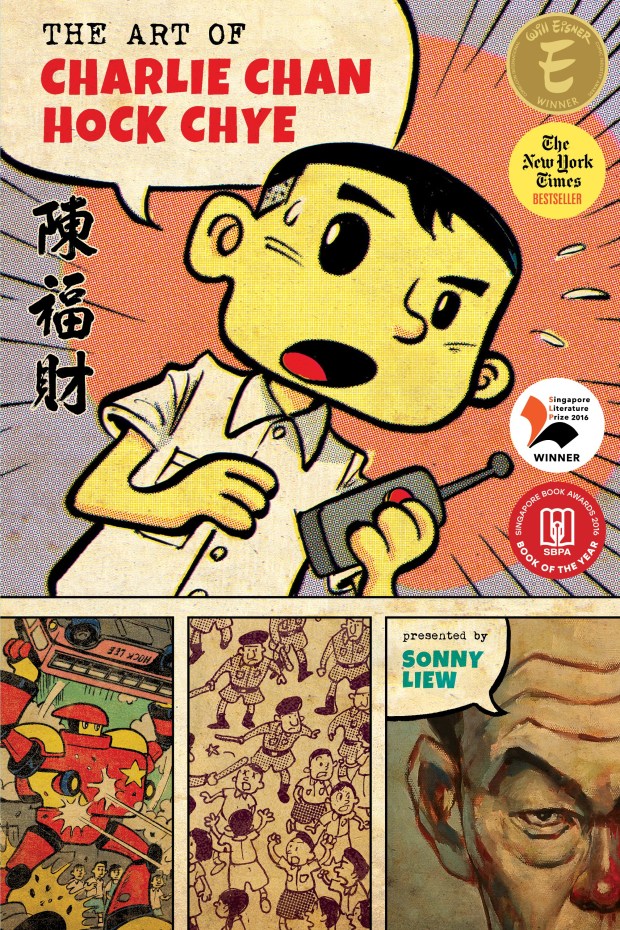

- The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye by Sonny Liew

Sonny Liew’s book first shot to fame when the National Arts Council withdrew their publishing grant just before its launch, saying that the work “potentially undermines the authority or legitimacy” of the government. But The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye is a gorgeous, well-crafted graphic novel in its own right, and won Liew three Eisners this year. It’s a beautiful telling of Singapore’s history—and imaginings of what might have been—through the life experiences of the fictional comics artist Charlie Chan Hock Chye.

- Beyond the Blue Gate by Teo Soh Lung

This book is a must-read for anyone who wants to understand why activism and civil society in Singapore is where it is today. Teo Soh Lung was one of the over 20 lawyers, activists and social workers arrested and detained without trial in 1987. She talks about this experience in her memoirs, offering a horrifying glimpse of how power can be exercised in oppressing one’s own citizens.

This magazine is an independent endeavour by a group of young journalists. It’s an annual volume because it’s largely self-funded and put together as a passion project while the team juggles all their other obligations. They’ve started putting some of their pieces (from their first volume published last year) on their website—check it out for Singaporean stories, essays and interviews.

Singlish sayings

Die die must try some chicken satay in Singapore

- Kiasu: Singaporeans were feeling FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) long before FOMO was even a thing. This Hokkien term refers to a fear of losing out, and is often used to refer to a competitive streak among Singaporeans.

- Why liddat? : Liddat (pronounced lye-dat) is basically “like that” squished together. “Why liddat” is often an exclamation of unhappiness, used when one doesn’t approve of the situation. For example: if a friend tells you that your favorite shop has run out of your favorite ice cream flavour, it’s perfectly acceptable to go, “Aiyah, why liddat?”

Alamak! I dropped my phone off the top of the Marina Bay Sands Hotel!

- Alamak! : This is a common exclamation for when something goes wrong or is clearly problematic.

- Die die must try: You see this sometimes in food blogs and reviews. When someone says that something is “die die must try”, they mean that it’s so good that you just have to give it a go.

- Chope: This is more an activity than a phrase. To chope something means to reserve it. For example, you can leave a tissue packet on a table at a hawker center to chope that table for yourself (and this works!)

Know before you go

- Singapore is a city and a country. It’s also a collection of islands (one larger and lots of smaller ones) at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula in Southeast Asia. Local empires settled the islands from the 2nd century. Fast forward to 1819, when Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles founded Singapore as a trading post of the East India Company. Singapore was ceded to Britain after the East India Company collapsed, then became an independent city-state in 1965, when it separated from Malaysia. Since then it has been busy molding itself into a sleek, modern, efficient, multicultural financial hub. But as a city-state there is little outside, which means that many of the people who come to the city to work are immigrants, and Singaporeans who want to leave the city have no choice but to emigrate.

- Don’t be a potato; learn some Singlish. There are four official languages in Singapore: English, Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil. English has been the predominant language of instruction in schools since the 1970s, so English-speaking visitors will do just fine in most circumstances. But there is also Singlish. Developed from interactions among Singapore’s various ethnic groups, Singlish is a hybrid language, with smatterings of other official languages and Chinese dialects, such as Hokkien. The result: gems like gostun, which means “to back a car up,” derived from the English nautical phrase “go astern.” Or jialat, which is a local version of “oh no!,” derived from the Hokkien phrase “to sap energy.” There is no one way to speak Singlish. Some words and phrases are widely understood, but each version of the language is influenced by factors such as ethnicity—Chinese Singaporeans’ Singlish has slight differences from that of Malay or Indian Singaporeans. Singlish is also a marker of education and class. Well-educated Singaporeans are expected to code-switch seamlessly between Singlish in casual settings and English in formal situations, while Singaporeans who haven’t had the same level of English education might only speak Singlish. A Singaporean who never speaks Singlish is considered jiak kantang, literally translated as “eat potato” (as opposed to the Asian tradition of eating rice), because they behave more Western (read: more white) than Asian.

- Don’t take racial harmony at face value. From the state’s point of view, Singaporean society is organized into four racial groups: Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Others. While the Malays are recognized as the indigenous community, the Chinese form the majority of the population (75 percent), due to the high levels of immigration from China after 1819. This Chinese-Malay-Indian-Others model, also known as CMIO, has practical implications, such as where people can live. Public housing uses ethnicity, among other variables, (such as age, household income, and marital status), to determine how many people of each race can live in a particular block of flats. Much is made of Singapore’s “racial harmony,” and the race riots of the 1960s are held up as a bogeyman to warn Singaporeans not to stoke unrest between ethnic and religious groups. But the fact is that Chinese Singaporeans enjoy a vast amount of privilege, from the special assistance some schools receive to ensure their students remain connected to Chinese culture to the fact that “bilingual” in a job ad almost always implies that the applicant should speak English and Mandarin. There are other racist practices in Singapore, too: Ror example, it is totally legal for a landlord or real estate agent to say in a property ad that Indian tenants need not apply.

- Food is a national pastime. Along with shopping, eating is one of Singapore’s key diversions. Singaporean cuisine is a wonderful mongrel of Malay, Chinese, Indian, Indonesian, and Western flavors: Fusion was the norm here long before it fell in and out of fashion in the West. The same dish can be interpreted and prepared a little differently. For example, Indian, Chinese, and Baba-Nyonya (Straits Chinese: a mix of Malay and Chinese) food stalls all have their own versions of Singapore’s celebrated dishes: fish head curry, Singapore crab. The sumptuous laksa—a noodle and curry feast with a spicy coconut broth—can be found in both Chinese and Malay establishments. Laksa comes in many guises in Singapore, but the Katong laksa, made with thick vermicelli noodles cut into pieces and sprinkled with prawns and fish cake, is a favorite.

- Hit Lau Pa Sat in the evening. This hawker center provides the perfect blend of tourist attraction and food haven. In the heart of the Central Business District, it’s been a marketplace for Singapore since 1894 and was declared a national monument in 1973. It houses a ton of hawker stalls, which offer everything from Singaporean to Costa Rican cuisine. Come evening, a small street adjacent to the structure is closed off and dozens of satay vendors emerge for a night of smoky, delicious indulgence.

- Singapore is kind of a democracy… The People’s Action Party (PAP) swept into power in 1959 and has stayed there. There have been three prime ministers, beginning with Lee Kuan Yew, who governed for over three decades. His son, Lee Hsien Loong, is the current prime minister. The PAP is still popular in the country. It won the last general election, in September 2015, with almost 70 percent of the vote; and Lee Kuan Yew’s death, in March 2015, inspired prolonged and tearful national mourning.

- …but it’s not that free. The government limits political opposition and citizens’ rights. The government has a say in the appointment of major shareholders and the editor-in-chief of domestic media, so papers tend to toe the line. The Elections Department falls under the purview of the prime minster, and electoral boundaries shift before every election in ways that spark suspicions of gerrymandering. Dissenting voices are kept in check through defamation lawsuits and contempt of court cases. Singapore is often described as an authoritarian state, but the reality is far more complex. The government’s presence is pervasive—from government-linked companies in industry to state-endorsed dating events—but day to day the average Singaporean doesn’t live in fear of being watched or arrested. If you have no involvement in politics or political activity, it doesn’t feel like there is a consistent lack of freedom in Singapore. If you try to organize a protest or a public forum, however, or if you work in the arts, the impact of censorship and control is more direct. In addition, the leadership insists that Draconian punishments for drug offenses and an almost mandatory death penalty are the trade-off for Singapore’s peaceful, prosperous, and safe society.

- Understand the Big Man. The face of Lee Kuan Yew is everywhere. He was the country’s first prime minister and the founding father of modern Singapore. For better or worse, his politics and personality have shaped many aspects of Singaporean life and the Singaporean psyche. His concepts of Confucianism and control have strongly influenced local politics; his belief in tough love and hard truths underpins the government’s generally anti-welfare perspective and its commitment to retributive justice, in such forms as corporal and capital punishment. His eugenicist beliefs have also affected the lives of Singaporeans, particularly those of low-income families, who are sometimes offered financial assistance in return for having fewer children. Yet Singapore has also achieved great success under Lee and his party. He was tough on corruption and succeeded in establishing a government that has been relatively corruption-free to date. His determination to make Singapore attractive to foreign investment has also been a major factor in the city-state’s wealth. For alternate histories, however, check out the memoirs of former political detainees, such as Beyond the Blue Gate by Teo Soh Lung, or Comet in Our Sky, by Lim Chin Siong, an account of Siong’s role in the anti-colonialist movement. His political career was ultimately crushed by Lee Kuan Yew.

The “know before you go” section of this article was originally published on Roads & Kingdoms on Nov. 16, 2015 and has been condensed.