Loota was working late one Sunday evening in 2013 when a truck full of army officers stopped outside his butcher shop. They hopped out and ran toward a group of teenage boys playing at a pool hall behind his stall. The boys scattered; a few got away by slipping out of their shirts as they were being grabbed

The 43-year-old butcher walked out to see what was happening just as the soldiers were throwing two boys into the back of their truck. They seized Loota too.

“They started kicking, hitting me on the ground and jabbed me into the vehicle, where they stepped on me and started kicking me all over,” Loota said.

Over the next few days, he was taken from one police station to another, and then to a detention center in Ngorongoro Conservation Area, a UNESCO World Heritage site near Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park. Loota says locals call this place “Guantanamo.”

Loota was stripped naked and beaten by three military officers, while five others sat and watched, taking notes. He says they took the shoelaces from their jackboots and tied one end around his genitals, and the other around a brick, which they threw over his shoulder.

The officers forced him to stand like that for hours as they interrogated him: “Who is killing elephants? Have you ever killed elephants?”

“It is as if you are dying,” says Loota, who spoke on the condition that his last name not be published, for fear of retaliation by the government. “You will be beaten harder if you pretended to be dead.”

Loota was among hundreds of suspected poachers detained in 2013 during Operation Tokomeza, a nationwide crackdown on elephant poaching. The operation tasked Tanzania’s military, police, local militias, and wildlife rangers with finding and arresting suspected poachers in and around Tanzania’s national parks and game reserves.

During the roundup, which resulted in serious human rights abuses, Loota had been wrongly accused of elephant poaching. He was later acquitted by a judge.

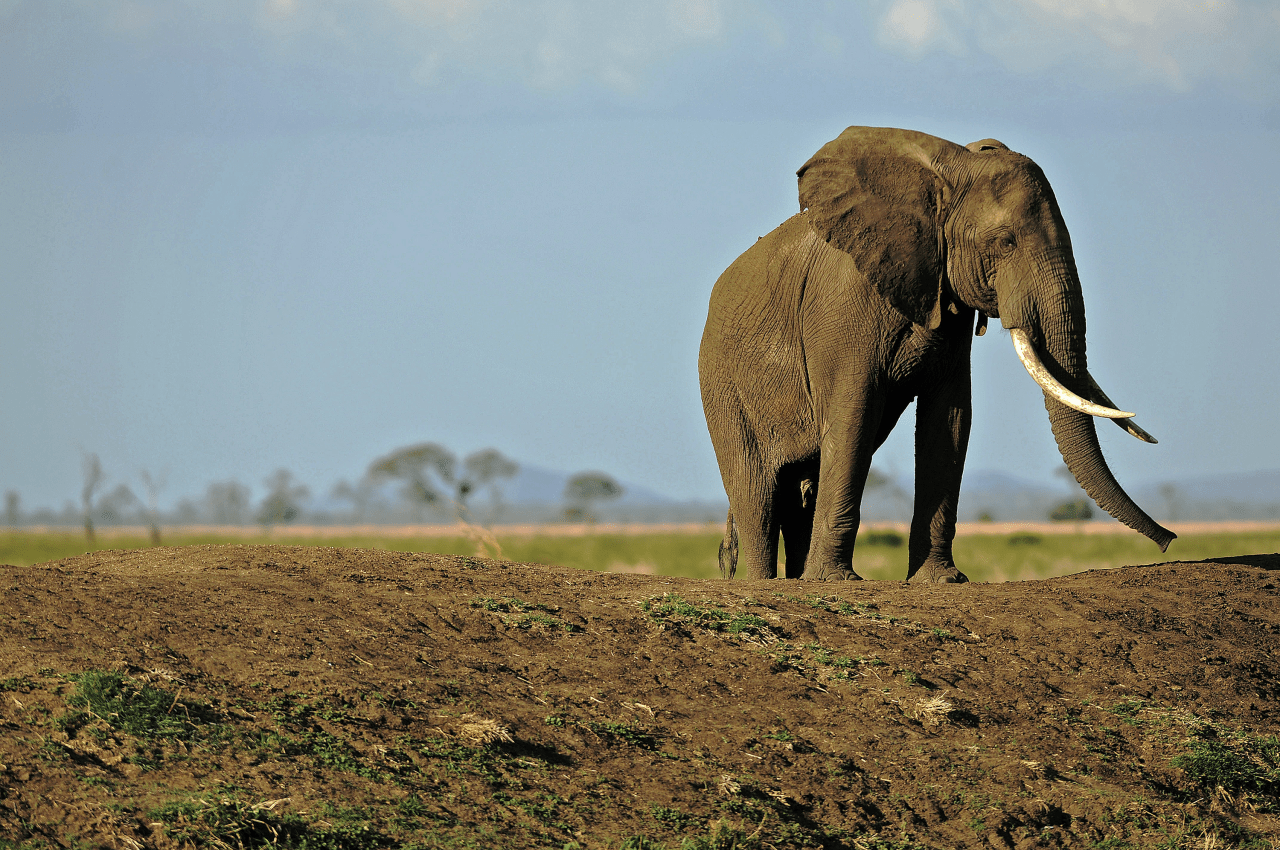

Sixty-five thousand elephants—60 percent of the population—disappeared from Tanzania between 2009 and 2014. In Selous Game Reserve, the epicenter of the crisis, 90 percent of its 110,000 elephants have vanished during the past four decades. At that rate the last of them will be gone by 2022, according to a June 2016 report by the World Wildlife Fund.

Desperate to save the country’s elephants (and tourism industry), Tanzania’s government is on the verge of unleashing a new anti-poaching strategy that employs military weaponry, training, and tactics and relies heavily on intelligence gathering and analysis to infiltrate the top of the crime rings.

Shortly after taking office in November 2015, Tanzania’s president John Magufuli appointed an active military man, Maj. Gen. Gaudence Milanzi, as permanent secretary of the Department of Natural Resources and Tourism. Speaking at a military training exercise for rangers in May, Milanzi endorsed Tanzania National Parks Authority’s request to convert antipoaching units from a civilian to a paramilitary force, according to local press.

Tanzania’s latest plans come as governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) across the continent confront increasingly sophisticated and well-resourced poaching syndicates, with both sides resorting to more militarized tactics.

Dozens of rangers in Africa are killed in the line of duty every year. Often overstretched and underfunded, these rangers are tasked with the dangerous job of protecting wildlife from heavily armed poachers and militias involved in trafficking ivory, drugs, and weapons.

In response, some countries and NGOs are arming rangers with heavy weaponry, deploying new surveillance technology like drones and sensors, and applying advanced intelligence analysis (and in some cases artificial intelligence).

South Africa, Kenya, Botswana, Cameroon, and Zimbabwe have also mobilized their national militaries to help fight poachers, according to the Geneva-based monitoring group Small Arms Survey.

“Nowadays African states continue to employ antipoaching strategies involving shoot-on-sight policies and sweeps of villages and parks to forcibly remove poachers,” wrote Khristopher Carlson in the Small Arms Survey 2015 report “In the Line of Fire: Elephant and Rhino Poaching in Africa.”

Past human rights abuses committed by Tanzania’s antipoaching forces cast a long shadow over its increasingly militarized fight against poachers.

Operation Tokomeza was suspended after a few weeks because of widespread allegations of murder, rape, torture, and theft by the anti-poaching forces. A parliamentary investigation documented atrocities against local villagers—including 13 people killed—and four government ministers were dismissed.

Numerous interview requests to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism were declined, and emailed questions regarding the allegations were not answered. The Tanzania National Parks Authority did not respond to requests for interviews.

Even after Tokomeza was disbanded, Loota was held in detention without charge. By the time he went to court, he was unable to stand, and sitting was painful. His genitals were swollen, and he had multiple fractures. The judge ordered medical care, and he was hospitalized for a month.

Upon release from the hospital, Loota was charged with killing an elephant with two men he says he had never met. He spent a year in prison awaiting trial, with bail set at 20 million Tanzanian shillings—about $9,133 U.S. dollars—an impossible sum for him to pay.

“At long last the judge found me not guilty. He also said that I could file a court case to claim damages. But I cannot compete against the government because I am very poor,” says Loota, who has never received compensation.

Nearly three years later, he is impotent.

A report released by the Legal and Human Rights Centre (LHRC) documents seven deaths at the hands of the antipoaching units during Operation Tokomeza. This includes one woman, Emiliana Gasper Maro, who was allegedly beaten to death because her husband was a suspected poacher. Another woman was reportedly gang-raped at gunpoint by three soldiers. Human rights monitors suspect that many more crimes have gone unreported.

Pascience Mlowe, an LHRC lawyer and co-author of the report, says that even before Tokomeza, corrupt police often arrested and fabricated poaching charges against villagers living on the outskirts of the park.

“They used it as an opportunity to gain money from people,” Mlowe says. “They could come to a village and arrest people and say, We suspect you are a poacher. It’s easier for them to pay money, and then they are released.”

An LHRC report from 2011 reports several allegations of brutality by Selous rangers, including one local person who said that the rangers were known for torturing suspects and then leaving them alone in the national parks, where they were at risk of being attacked by animals.

Mlowe says torture is also commonly used as an interrogation method in crimes other than poaching.

Human Rights Watch has documented the police torture of LGBTQ individuals, drug users, and sex workers. Tanzania has not ratified the International Convention Against Torture.

According to Mlowe, there haven’t been reports of abuses since 2013. But he fears that the new antipoaching strategy, which is intelligence-based, could open the door for such torture again.

Loota’s home is not far from the entrance of Tarangire National Park, which boasts one of the densest elephant populations in Tanzania. Hordes of tourists flock here every year hoping to spot the giant gray bodies lumbering among the green and gold grasslands that hug the Tarangire River. It’s not hard to do, especially during the dry season, when elephants, giraffes, lions, zebras, gazelles, and wildebeests congregate around one of the last remaining water sources in the area.

Long before these animals shared their habitat with binocular-wielding tourists, before ivory prices soared in East Asia, before the government of Tanzania designated this land off-limits to local people, hundreds of communities survived on the natural resources of the Masai grasslands. For generations families farmed, hunted, raised cattle, and harvested charcoal in and around Tarangire.

Few visitors interact with villagers living on the outskirts of the park, most of whom see little or no benefit from tourism. Instead, some villagers have faced indiscriminate arrests, surveillance, violence, and extortion by law enforcement officers.

Robert Mande, a law enforcement official who said he was an architect of Operation Tokomeza, denies that rights abuses took place. He alleges that government officials fabricated the atrocities in order to discredit the operation because the units were getting too close to implicating corrupt officials connected to the top of poaching syndicates.

Of those killed during Tokomeza, Mande says, “They were not killed intentionally, but they were killed during exchanging fire in the operation.” That claim is not supported by the parliamentary investigation or LHRC’s reports, which document beating and torture of unarmed people.

During Operation Tokomeza, Mande was in charge of law enforcement at Ngorongoro Conservation Area, where Loota and others were held. National Geographic spoke to two other people who alleged torture in the same detention center they call Guantanamo.

In an interview in May 2016, Mande said that he was slated to be appointed commander of a new intelligence-based anti-poaching strategy called the Wildlife Crime Unit. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism did not respond to questions on the work of the Wildlife Crime Unit, and whether Mande will be involved. In July 2016, local news reported Mande was appointed acting deputy director of the poaching unit of Tanzania Forest Service.

Mlowe of the Legal and Human Rights Centre says that many of those who perpetrated abuses during Tokomeza weren’t charged or removed from their posts. And human rights defenders are concerned that the militarization of Tanzania’s conservation efforts could endanger local people living around the parks—again.

This story was originally published by National Geographic on Sept 19, 2016.