Uruguay hasn’t always been this way.

Like many of its neighbors, the country was under a military rule not long ago — from 1973 to 1985, when thousands of Uruguayans were detained and hundreds were tortured, killed, or disappeared by the military junta for alleged ties to leftist guerrillas.

Fast-forward three decades and this tiny nation with a population of nearly 3.5 million stands out as a beacon of progressive reforms in Latin America. Today, in a region where 97 percent of women of reproductive age live under restrictive abortion laws, Uruguayans have the right to choose; where the Catholic Church is influential and conservatism is on the rise, 37 percent of the country’s population identifies as secular; and where LGBTQ rights lag and trans people are often the target of violence, same-sex couples have the right to marry and adopt children.

Many of these liberal laws are the result of a flurry of relatively recent legislation. From October 2012 to December 2013, the country legalized abortion for all women under any circumstances (it’s the second nation in Latin America to do so, after Cuba), passed legislation allowing same-sex couples to marry, and in a world first, legalized the growth, sale, and use of marijuana for recreational use.

How did Uruguay emerge from more than a decade of repression to become one of the most progressive countries in Latin America, if not the world?

Uruguayans point to a combination of unique foundations, charismatic and forward-thinking leaders, and its small (and relatively homogeneous) population to explain why their country has become a laboratory for progressive laws.

The nation became an independent in 1825, after nearly three decades of being caught up in territorial conflicts between Spain and Portugal and later Argentina and Brazil. Uruguay’s first Constitution, adopted in 1830, was modeled after the U.S. and French charters. In the 1870s, Uruguay introduced free universal primary education.

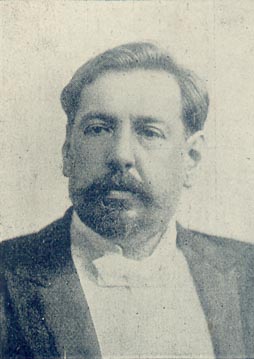

Uruguay’s early years were marked by armed conflict between the conservative Blanco Party and the liberal Colorado Party, and fighting continuing into the 20th century. In 1903, Colorado leader José Batlle y Ordoñez was elected president, effectively ending more than five decades of on-and-off civil war. Batlle y Ordóñez, a former journalist and the scion of a prominent Colorado family, is widely considered the father of modern Uruguay.

Batlle y Ordóñez was a major proponent of secularization. His government banned religious symbols in public hospitals, removed religious references from public oaths, and legalized divorce. By contrast, neighboring Argentina legalized divorce only in 1987, and Chilean lawmakers held out until 2004.

After his first term, he spent nearly four years in Europe, where he became convinced that in order to become modern, Uruguay would need to advance workers’ protections and women’s rights. He returned to office in 1911, and in the ensuing years, the country passed laws limiting work days to eight hours, providing unemployment compensation, and guaranteeing universal suffrage.

The Great Depression brought an end to that era of progressivism. Economic malaise and rising unemployment gave way to growing unrest. President Gabriel Terra, a Colorado who became president in 1931, dissolved Parliament and suspended civil liberties in 1933, ushering in a period known as the dictablanda, or soft dictatorship.

The Cuban revolution in the 1950s had an immense impact on leftist movements across the region, and in Uruguay, that came in the form of the Tupamaros, formally known as the National Liberation Movement. During its nearly decade-long existence, the group became notorious for killings, bank robberies, and kidnappings, including that of an American CIA adviser who was executed by Tupamaros fighters in 1970.

The state responded with a brutal crackdown, and the military took power in 1973 and ruled with an iron fist until 1983. Hundreds of people were killed or disappeared, and dissidents were imprisoned and tortured. Unions and political parties were banned, and the press was heavily censored. From the late 1960s to mid-1980s, most South American countries were ruled by military dictatorships, and Uruguay was no exception.

The military ceded control in 1985, after accusations of human rights violations. That year a controversial amnesty measure was passed in order to protect police and military personnel from prosecution for crimes during the dictatorship. It was a way of closing a dark chapter of the country’s history, but it left many open wounds. With the end of the military regime, dozens of political prisoners were freed. One of them was José “Pepe” Mujica.

Born in 1935 to a family of farmers, he joined the Tupamaros in the 1960s. The military government imprisoned him for 14 years for his activities, with more than a decade in isolation. At times, he was confined to a hole in the ground and went more than a year without bathing. He joined the Parliament in 1994 and was known for arriving on an old motorcycle. In 2010 he was elected president and went on to push progressive reforms, or in his words, “social experiments.”

After taking office, at the age of 74, he became known worldwide as the pauper president. Eschewing the presidential residence, he lived in a humble home on the outskirts of Montevideo and drove himself to work in a 1987 Volkswagen Beetle. He donated about 90 percent of his salary to charity. He spoke of reconciliation, saying his time in prison taught him that hate is a luxury.

He led efforts to pass ambitious legislation, including a 2013 measure decriminalizing marijuana cultivation and recreational use, in an effort to combat drug trafficking. About 16 pharmacies sell pot to citizens and permanent residents who join a national registry.

Not everyone supports the marijuana law. A year into its implementation, fewer than half of Uruguayans are in favor of it. And Uruguayan banks told pharmacies selling marijuana that their accounts would be closed, after U.S. banks warned that they wouldn’t be doing business with Uruguayan financial institutions that served those pharmacies, to avoid contravening the Patriot Act.

The economic situation boomed, mostly thanks to an increase in exports, but Mujica, who left office in 2015, regretted not being able to achieve major reforms in the education system. His legacy is somewhat mixed, and he may be more admired outside Uruguay than in his country.

Despite its liberal reforms, Uruguay is far from a utopia. Talk to its residents, and they will complain about high costs of living or the security situation. The homicide rate, although still one of the lowest in the region, has grown in recent years. But on the bright side, the small country’s economy has somehow managed to outperform its powerful neighbors’ and, at least for now, bucked the gloom.