I

If you wanted to eat, you had to work. That’s how Kaui Kapuni Manera was raised on the Hawaiian island of Molokai in the 1960s. As one of seven children brought up by her grandparents, Manera contributed to every meal by scouting for fish, gathering edible seaweed or harvesting from the star fruit, guava, and breadfruit trees that grew in abundance on the family’s two-acre plot edging the sea.

“When momma said ‘go out there and get lunch’ she meant it,” remembers Manera, now 61. “If she told us to go out and pick limu, it was an all-day job. If we walked to the school, we were expected to carry oranges home in our shirts. Even when we were playing, we were gathering. I used to grumble, ‘How come we can’t have canned Spam like the other kids?’”

It wasn’t until the family dinner started to include those fashionable Spam cans that Manera realized she lived in poverty.

“When my grandfather passed away, there was no one to raise the pigs or harvest the taro patch anymore,” Manera says. “My grandmother was blind, and we were just kids. So we started getting food stamps. And that’s when we started to go to the market. That’s when we finally got to have Spam. That’s when I really understood that we weren’t going to eat as good anymore. Yes, we were poor, but, in other ways, living off the land had made us really rich.”

Once an object of yearning, Spam became a flag of the shame born of needing U.S. government assistance. Nevertheless, Manera savored the salty meat that replaced her grandfather’s hand-pounded poi and fresh-caught fish.

“I’m grateful that the government kicked in,” says Manera, who is Native Hawaiian. “I was embarrassed at the time, but now I know that’s the only way we survived.”

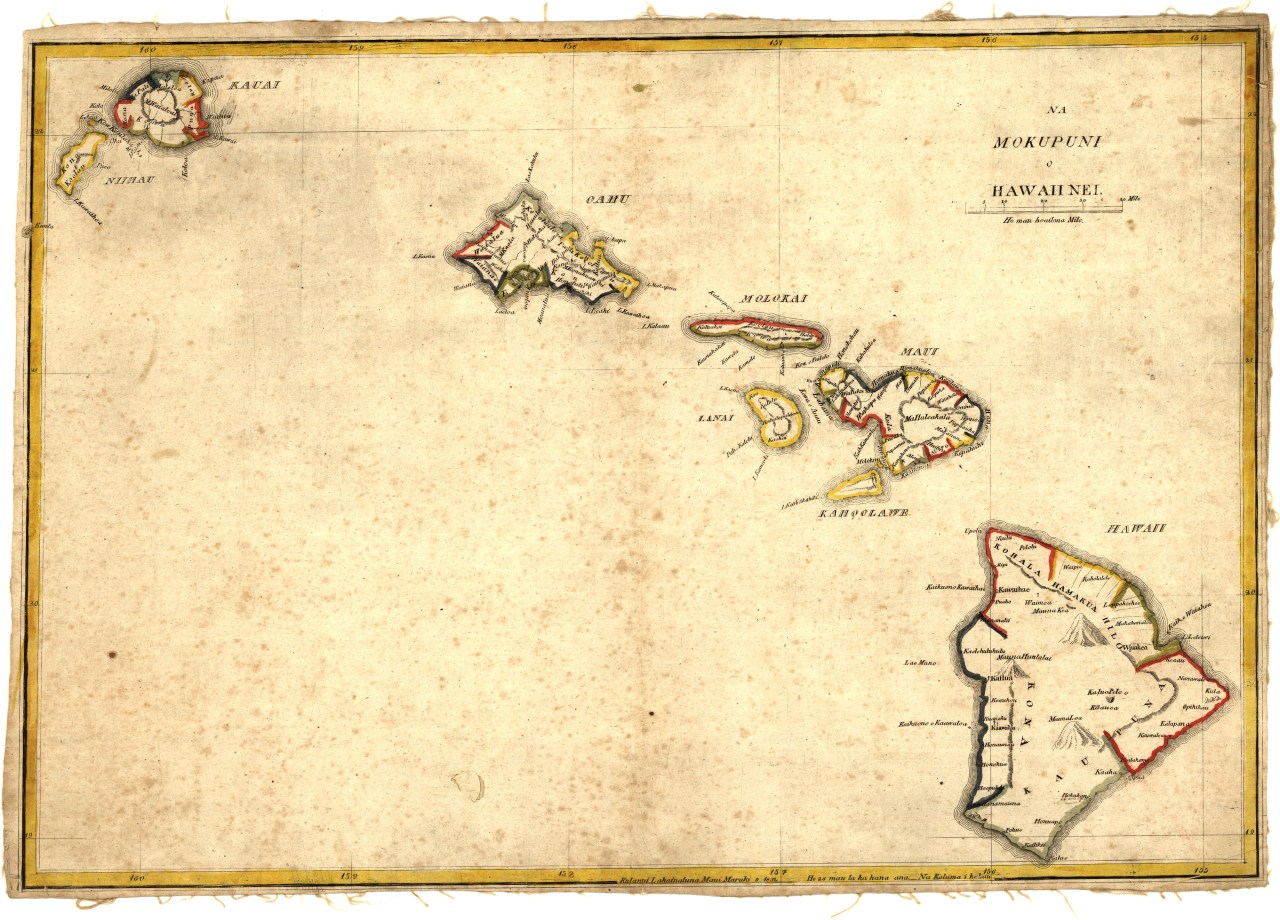

On Molokai, where more than 60 percent of the island’s 7,400 residents are of Native Hawaiian descent, a longtime rejection of Americanization and urban development has kept alive a way of life that closely resembles that of traditional Polynesia. And because Molokai has fewer visitors than any other Hawaiian island, as well as the largest indigenous population in the state, it is one of the only places where the authenticity of Old Hawaii is said to still exist.

Of course, when you reject modernization, you risk limiting economic growth. Today, on this island without traffic lights, the trade-off of a simple, down-home lifestyle that’s still largely intact is that good work is hard to find. An island-wide job shortage, coupled with the reality that many of the jobs that do exist fail to offer a livable wage, has bred a generation that relies on a combination of government assistance and traditional subsistence living practices to get by.

I just want to work hard and nurture and perpetuate what we are as Hawaiians.

“A lot of Hawaiians who depend on government assistance are pissed because it doesn’t provide a great life, and a lot of the Hawaiians who don’t are pissed because it’s hard to get on without it,” Manera says. “Everyone’s so pissed today, and I was angry for so long, and now I just don’t want any part of it. I don’t want that anger in my house, I don’t want that anger in my family. I just want to work hard and nurture and perpetuate what we are as Hawaiians.”

This is the backdrop to which a fiery political debate over Hawaiian sovereignty is erupting. Indeed, the debate has been flaring since the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. government. What’s different now is that Native Hawaiians are for the first time being presented with a new means of attaining some degree of political autonomy.

In September 2016, Native Hawaiians won access to a new process by which the United States would form a government-to-government relationship with a unified Hawaiian nation. Previously unavailable to indigenous Hawaiians, this brand of quasi-sovereignty through federal recognition has long been employed by Native Americans and Alaska Natives to bolster the political power of tribal nations.

A shot at federal recognition is something that some Native Hawaiians have been fighting for—and other Native Hawaiians have been fighting against—for a very long time. Whether they’ll seize it, and how it might serve to ameliorate some of the injustices the Native Hawaiian community has endured in the last century, is yet to be seen.

“People come here to see rainbows and jumping whales, but they learn pretty quick that there’s a lot more going on,” says Koa Kakaio, who is 30.

A California-born Native Hawaiian who relocated to Molokai to discover his roots, Kakaio works jobs in construction and graphic design while also operating his own online apparel business. He is smart and enterprising, but despite working three jobs Kakaio still makes a paycheck-to-paycheck living.

All told, 35 percent of Molokai’s population receives federal food aid, while more than a third of the residents report that they farm, hunt and fish to keep fed. Complicating matters further is that a century of deleterious colonization has bred a new reality in which far fewer Native Hawaiians own any of the lands on which their ancestors long cultivated an impressive bounty of food.

Simply put, it’s harder than ever to carry out the old Hawaiian way of life on this tiny isle. Native Hawaiians no longer have access to much of the land that has been bought up by Asian and American businesses, federal and state government and transplants from places ranging from Kansas to the Philippines. Most no longer speak their native language that for a time was outlawed in Hawaii classrooms.

Throw in widespread land degradation—the fallout of a defunct sugar and pineapple plantation industry—and a new and controversial biotech seed business that provides some of the island’s only well-paying jobs, and you’ve got a web of political and cultural complications that not even this sleepy little island can escape.

“Everybody’s selling this place as a paradise and everybody’s trying to sweep the history under the rug,” Kakaio says. “Sometimes it feels like Hawaiians are completely written out of history. That’s why people get so mad. Then you bring us back when you want to make Moana into a Disney princess. People are angry.”

But there is no perfect place on this earth.

But more than a hundred years after Hawaii’s last monarch was imprisoned in her palace and forced to abdicate the throne, some wonder whether they can trust Washington’s motives in offering to strengthen the political autonomy of Native Hawaiians through federal recognition.

“Why should we do nation-to-nation?” says Ruth Yap, an 80-year-old Native Hawaiian from Molokai. “So that then they’ll turn around and try to put in an oil pipeline that threatens the water we drink? From what I can see that they’re doing over there with the Indians, we don’t need to get ourselves involved in that.”

Proponents of federal recognition say achieving the nation-within-a-nation status under the U.S. government would eradicate at least this one injustice: Indigenous Hawaiians are the only Native group in the nation that have not been able to rebuild some semblance of political autonomy. Reversing this situation, supporters say, could help to empower the group, who, compared to Hawaii’s other racial groups, are disproportionately afflicted by illiteracy, incarceration, obesity, and homelessness.

“I believe the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists, it was never extinguished,” says Timmy Leong, a champion of total independence who is gentle, bespectacled and bearded. “When you think of Donald Trump and that whole birther movement, saying that Obama was born in Kenya—he got it right. He just got the country wrong. Obama wasn’t born in the U.S., he was born in the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

How long are we going to wait to get our land back?

Apart from federal recognition, there are other roads to sovereignty. Total independence is a goal desired by many Native Hawaiians who argue that it’s still possible to force the U.S. government to retreat from the Hawaiian Islands by the order of an international court. Supporters of this more radical route to sovereignty point out the United States has already admitted its faults: In 1993, Congress formally apologized for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, conceding the nation’s role in seizing land without compensation or consent and expressing remorse for its contributions to “the suppression of the inherent sovereignty of the Native Hawaiian people.”

“Anytime the usurper offers you something on a silver platter, I see it as bait,” says Mike Weeks, an advocate of total independence.

Weeks, a Molokai native, routinely gives away 40 percent of the vegetables he harvests on his one-acre farm because there are plenty of hungry mouths but not enough folks with money to pay for it.

“The thing is, America didn’t steal our home; it stole our minds,” Weeks says. “We’re laying back enjoying welfare when we should be fighting for a better future. Give us one or two more generations, and we’ll get our home back.”

Opponents of total independence insist that it’s naive to entertain the fanciful notion that the U.S. government and its military would actually pack up and leave these strategically located isles. If it did, critics say, the blow of losing American citizenship would leave Native Hawaiians scrambling for basic resources, such as food. Imports account for about 90 percent of what feeds Hawaii’s residents and tourists.

“I’m Hawaiian born and raised, but I wasn’t born under the Hawaiian Kingdom,” says Pilipo Solatorio, a Navy veteran and respected Native Hawaiian cultural practitioner who lives a traditional way of life in the same secluded Molokai valley as his ancient ancestors. “What my grandparents tried to teach me is that you take the good from the Hawaiian way and you blend it with what’s good about America. They believed that we must move forward, not backward.”

“I cannot blame the people of today for what happened in that period. I have no grouch with America. How can you get mad at America when you’re born in America? Yes, I am Hawaiian. And no, America isn’t perfect. But there is no perfect place on this earth.”

In a recent push by Native Hawaiians to rebuild their political autonomy, nearly 90,000 Native Hawaiian voters became certified to participate in a 2015 election aimed at assembling a delegacy to write a constitution for a new sovereign nation. Organizers planned a month-long summit in Honolulu, where Native Hawaiians elected from around the globe would design a legislative structure and a bill of rights. Hawaiians could then move to legitimize their contract of self-governance by seeking recognition from the United States or an international governing body, such as the United Nations or the International Court of Justice in The Hague, Netherlands.

But the U.S. Supreme Court ordered election officials not to count the ballots, prompting Native Hawaiian leaders to terminate the vote. The court order was triggered by a lawsuit by two non-Native Hawaiians who weren’t eligible to participate in the election, and four Native Hawaiians who argued that race-restricted voting is illegal.

The lawsuit is still making its way through the courts.

With the election called off, some candidates for delegate seats still chose to convene in Honolulu at an abbreviated convention, during which a document to steer self-determination was drafted. But without a means of conducting a legal vote, there was no way for Native Hawaiians to ratify it.

A retired firefighter and Vietnam veteran, 67-year-old Bobby Alcain says he did not support the ambitions of those who convened to write a new Native Hawaiian constitution because, in his opinion, they fell too short. He wonders—unless Native Hawaiians are returned to the land that has been bought up by foreigners, how can a new constitution do anyone any good?

Alcain’s coming-of-age as a Native Hawaiian was set in motion by his experience in the U.S. military. It was only after he suited up in uniform and went overseas that his mind opened to the idea that he was different from most of the other Army men he had fought alongside.

“I thought I was a true blue American,” Alcain says. “But I had no idea who I was. When I came home to Hawaii, I spent a year in the library reading every book I could find about what it means to be a Hawaiian, and I realized that I wasn’t the same as the other guys. Eventually, I started to plant things in the ground, because it’s very hard to be Hawaiian if you’re not connected to the earth. To heal the land is to heal yourself.”

Today, at the small farm where he grows copious vegetables and fruit, Alcain welcomes anyone—friend, stranger or tourist—to visit and take freely from his harvest. In keeping with Native Hawaiian tradition, there’s just one rule—no one may take more than he or she alone can eat.

“When you start caring for the earth, you start to care for everything,” says Alcain, who wears his hair down his back in a long, slender braid. “You start caring for the plants, for the bugs, for the animals, for people around you, for strangers. That’s the meaning of aloha; it’s not just a greeting you hear at the airport.”

In Alcain’s view, the most searing injustice of the U.S. takeover of the Hawaiian island chain is that so many Native Hawaiians have been removed from the land on which their entire culture is predicated. To care for the land and sea as ancestors is to fulfill the cornerstone of what it means to be Native Hawaiians, Alcain says.

“Right now, Hawaiians don’t own a piece of dirt,” Alcain says. “The U.S. took all of it away. Now, it’s easy for me, by myself, on this little piece of land that I’m caring for, to live a life of sovereignty. I can say I’m sovereign and no one is going to stop me. But sovereignty isn’t about the me, it’s about the we. How long are we going to wait to get our land back?”