Hong Kong is one of the world’s truly cosmopolitan cities. It is a melting pot of native Tanka, mainlanders, descendants of British colonists, and immigrants from corners of Eastern Europe and South Asia, among other places.

My family is quintessentially Hong Kong: I’m an ethnic Indian, raised by two thrill seekers who grew up in Japan and moved wherever business was booming. I’ve been to India a few times, but Hong Kong is the only home I’ve ever really known.

Hong Kong’s food reflects its diversity. You can have dim sum for breakfast, a stodgy pie for lunch at an age-old British pub, a fancy sundowner cocktail overlooking skyline views, and then a home-cooked curry for dinner. It’s all part of the local Hong Kong experience, a heady mishmash that feels entirely comfortable, no matter who you’re rubbing shoulders with.

What others might find confusing, I find incredibly comforting. People of all backgrounds have forged a common identity by mixing the cuisines of our parents and their parents, and new arrivals continue to build on and morph our culinary traditions.

Here are a handful of essential eateries that reflect Hong Kong’s diverse roots.

The English pub

Hong Kong became a British colony in 1842, after the First Opium War, and over the next several decades, waves of British sailors, merchants, soldiers, and government administrators settled in Hong Kong Island’s Central District, near the port. Many subjects of the British Empire—among them, Indians and Malaysians—came as well. Everyone brought foods and flavors from home.

Jimmy’s Kitchen is one of Hong Kong’s oldest British pubs. It opened in 1928 and serves up pub staples like shepherd’s pie and fish and chips alongside charming English takes on international cuisine—chicken a la king, beef stroganoff, veal cordon bleu, and of course, Indian curries. That blend of cultures and cuisines would eventually influence the local Chinese in their own East-West concoctions.

Teahouses and banquet halls

As the trade of opium and tea saw Hong Kong become an essential colonial port, the city began its transition from backwater fishing village to global financial center. Nearly a million Chinese mainlanders migrated to the city during the 1930s, taking with them flavors from neighboring Guangdong province.

Many of these Cantonese men gathered in male-only teahouses—small huts that over time grew more grandiose. They ultimately transformed into the two types of quintessential Hong Kong eateries: dim sum restaurants, which are typically patronized during the day, and fancier banquet halls, which are visited at night.

Luk Yu Teahouse, a three-story dim sum restaurant that opened in 1933, pays tribute to the flavors of early Cantonese cuisine. In addition to classic dishes like har gow (shrimp dumplings), char siu bao (barbecue pork buns), and cheung fun (rice rolls), the teahouse serves complex dishes like fish maw (dried swim bladders) with shrimp paste, pork liver dumplings, and duck and chestnut pie.

Yung Kee is a four-story banquet hall that opened in 1942. It serves up greasy Chinese barbecued meats (roast pork, goose, and duck) and a variety of steamed or fried whole fish. It also serves controversial favorites like shark fin soup, bird’s nest soup, pig’s lung soup, frog’s legs, and shredded jellyfish.

What’s with the weird meats, you ask? During the colonial period, Cantonese cuisine was a nose-to-tail experience. British residents, who were generally much wealthier than their local counterparts, often snapped up quality ingredients, so the Chinese had no choice but to experiment with their food. Cantonese cuisine has somewhat devolved since those early days, and high rents have forced out many of Hong Kong’s more traditional eateries; many newer restaurants lack that anything-in-the-kitchen allure.

Soy sauce Westerns and cafe culture

Hong Kong emerged as one of the world’s most prosperous ports after World War II, and as many as 2 million mainlanders arrived in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. Many were fleeing forced labor and famine during the Cultural Revolution.

Chinese newcomers grew curious to try Western flavors, and many tried to create these dishes themselves. This resulted in two uniquely Hong Kong kinds of eateries: the soy sauce Western and Chinese cafes.

The soy sauce Western was initially considered an upscale institution, but as Hong Kong became a financial powerhouse, attracting some of the most high-end restaurants in the world, its status diminished. Today they’re considered kind of kitschy.

These are the original Asian-fusion joints: Think watery Russian borscht with local vegetables, gristly steaks on sizzling hot plates, and prawn cocktail in thousand island sauce. Some long-running soy sauce Westerns, like Tai Ping Koon, Queen’s Cafe, and Goldfinch (immortalized in Wong Kar-wai’s film In the Mood for Love) remain very popular, attracting nostalgics young and old.

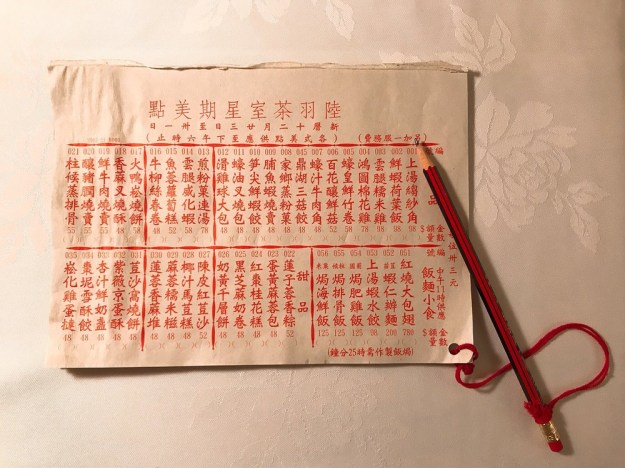

Chinese cafes also proliferated in the 1960s, catering to an emerging local middle class. Bing sutts sold cold drinks, such as red bean ice (red beans, sugar, and evaporated milk over ice)—a novelty at a time when home refrigeration was a rarity. Cha chaan tengs (tea restaurants) served affordable Hong Kong–style Western meals, like ham and eggs in a bowl of macaroni soup.

Bing sutts dwindled as more households were able to purchase refrigerators, but places like Kam Wah Cafe, China Cafe, and Mrs. Tang Cafe are still around and serve sweets like buttered pineapple buns with ice-cold milk tea.

Cha chaan tengs like Capital Cafe and Mido Cafe are everywhere still, and they continue to serve the city’s working classes with ham-and-egg sandwiches, curry beef and rice, and other hybrids alongside cups of yuenyeung (coffee-milk tea).

Typhoon shelters

The Tanka boat people are a nomadic southern Chinese ethnic group that has been living in small boats off Hong Kong’s shores dating back to the 18th century. At their peak in the 1960s, an estimated 150,000 people lived on Hong Kong’s waters, but as the city began to prosper in the 1970s, many started seeking economic opportunities on land, abandoning their boats in the harbor.

Hong Kong and Tanka entrepreneurs began converting these abandoned junks into eateries, which became known as typhoon shelter restaurants (named for the safe harbors that protected the boats from tropical cyclones). These became casual restaurants where locals could float on the city’s waterways and enjoy plates like steamed scallops and razor clams in garlic and chili, fried grouper with spring onions, and crabmeat loaded with red chilis.

In the mid-1990s, the local government clamped down on food safety regulations, forcing many of these restaurants to close. Some, including the popular Under Bridge Spicy Crab, survived by moving to land.

But many residents miss the middle-of-the-harbor setting. Shun Kee Typhoon Shelter, off Causeway Bay, opened in 2011 and is a throwback to the typhoon shelters of yore. Diners cram in tiny boats and gorge on seafood doused in as many spices as possible.

Modern Cantonese

On July 1, 1997, after more than 150 years of colonial rule, the U.K. handed Hong Kong over to China. Many locals, accustomed to Western-style democracy and freedoms, held their collective breath. Closer ties with the mainland had immediate effects on the food scene—rich mainland investors caused a meteoric rise in property prices, which raised rents and saw some of the city’s most renowned local eateries close down—and many feared an erosion of Cantonese cuisine.

A new set of chefs emerged in the years after the handoff determined to assert Hong Kong identity by bringing back Cantonese classics.

Lau Kin-Wai opened Yellow Door in 1997. It was casual and unpretentious, and its dishes took inspiration from all across the Pearl River Delta. The restaurant closed in 2015 (Lau then opened the current Kin’s Kitchen, which serves a similarly streamlined but more contemporary menu), but dozens of local chefs—among them Chan Yan Tak, the executive chef of Lung King Heen, the first Cantonese restaurant to snag three Michelin stars—have continued to perfect the Cantonese classics.

These days, chefs are increasingly seeking out fresh, local ingredients and using them to update nostalgic favorites. Mein by Maureen, Dragon Noodles Academy, and Bo Innovation serve up plates like wonton noodles with beef short ribs, razor clams in sake yuzu sauce, and roast pigeon with mountain yam and ginseng. Canadian-born chef May Chow is globalizing blue-collar cha chaan teng staples at Little Bao, Happy Paradise, and Second Draft, where dishes such as Hong Kong–style egg waffles and French toast are made out of sourdough and topped with foie gras butter.

Though Hong Kong’s is ever evolving, its history is very much alive at the dinner table. Bring your appetite.