The rot began at the root.

In 1914 Nigeria’s colonial master, Great Britain, set off a chain of events that would lay the foundation for the secessionist conflict known as the Biafran War. The conflict lasted from 1967 to 1970 and reportedly killed 1 million of the Igbo ethnic group, which had attempted to break away from the country. The Biafran War, though omitted in most history textbooks, is an important chapter in the story of Nigeria’s internal division.

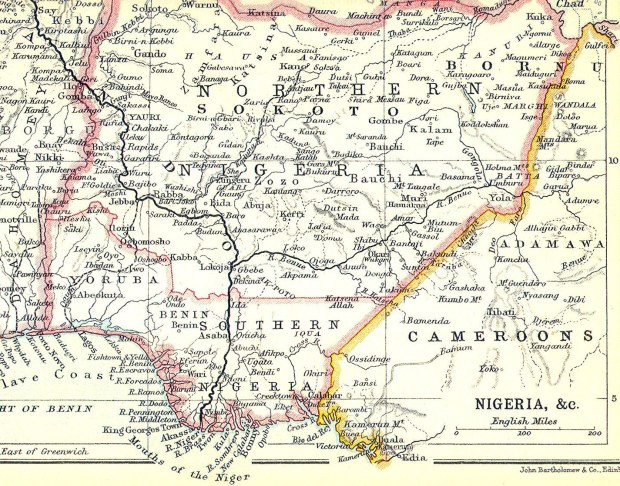

Before the advent of colonialism, Nigeria was not a nation-state as we know it now. It was a collection of independent native groups—more than 300 in total. The largest groups were the Igbos, who populated 60 to 65 percent of the southeast region; the Hausas, who populated 60 percent of the north, and the Yorubas, who made up 70 percent of the west. Each group was separated by distance and had its own distinct and proud political traditions, culture, language, and religion.

Ignoring the value of these distinctions, Britain “unified” the country in 1914, joining the Northern Protectorate (the Hausas) and the South (the Yorubas and Igbos) as one nation: Nigeria.

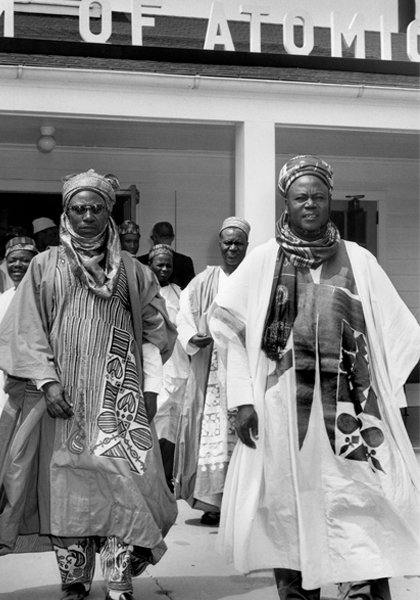

Of all the three groups, the Hausas were most adaptable to Britain’s administrative strategy, because they had always operated a feudal system that deposited all political power and religious authority in one person: the Sultan. The colonial power ruled the region simply by influencing his authority. The Hausas were also conservative and sought to preserve all traditions and systems. Conversely, the Igbos and Yorubas had more participatory and democratic systems of government in which citizens had a say in political and economic decisions. They were also, unlike the Hausas, more open to Christian missionaries and Western education. This accelerated industry and ambition in the south—especially among the Igbos—to become the first set of civil servants for the British government, among other early achievements. In addition, southerners began to move away from their immediate region in search of better economic fortunes. Eventually, Igbos were setting up successful businesses in the north and elsewhere in the south. Education and wealth soon joined the list of differences between the regions. Politically they remained sharply divided.

In 1946, Britain broke up the southern region into east (Igbo) and west (Yoruba). This further reinforced the differences between the regions, with political parties emerging in all three based on ethnic allegiances. The west and east then started to campaign for independence from Britain, a move that was roundly rejected by the north.

In 1953, a riot broke out in Kano between southern supporters of independence and northern opponents. It lasted four days and resulted in many deaths on both sides. At the same time, residents in the east and west had their own ideological differences too, even though they were both in the south. For one, they did not agree on whether Lagos, then dominated by the Yorubas of the west, should be the capital of an independent Nigeria. Because of this impasse, the leading political party of the west, Action Group, threatened secession from Nigeria at a London constitutional conference in 1954. Action Group demanded that the right to secession be included in the constitution of an independent Nigeria, but the demand was rejected by other regions, which would soon prove devastating for Nigeria in the years to come.

In 1956, oil was discovered in the southeastern region, and economic potential suddenly added fresh questions to the already brewing flashpoints between the regions. Who would control the oil? Who would benefit most from it?

Nigeria gained its independence in October 1960; four years later an election was disputed amid accusations of fraud. The foremost party in the north—the Northern Peoples’ Congress—emerged victorious, winning 162 out of 312 seats in the Parliament. The rest of the country bristled at this outcome, seeing it as the consolidation of northern political power and a continuation of the northern domination set in place by Britain.

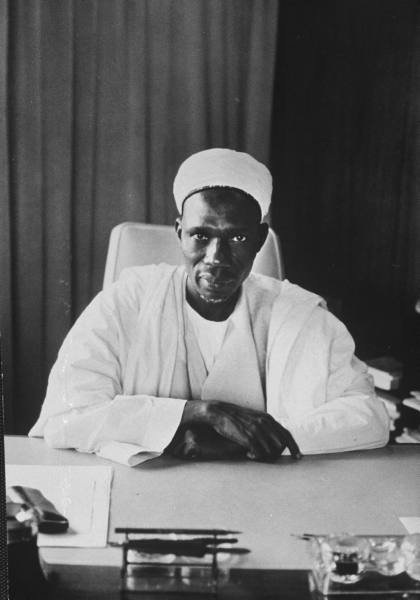

On Jan. 15, 1966, a group of majors—mostly Igbos from the east—led by Major Kaduna Nzeogwu attempted to overthrow the elected government in a coup, citing electoral fraud. They killed Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa and the premier of the northern region, as well as other northern officers in the military. The coup was broadly seen as a move by the Igbos to dominate the country, an accusation intensified in the context of their other perceived advantages.

The coup attempt was immediately thwarted by Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, also an Igbo but loyal to the Nigerian Army. He installed himself as head of state and jailed the coup plotters, but the damage was already done. Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu emerged as military governor of the eastern region, which he would declare independent a few months later.

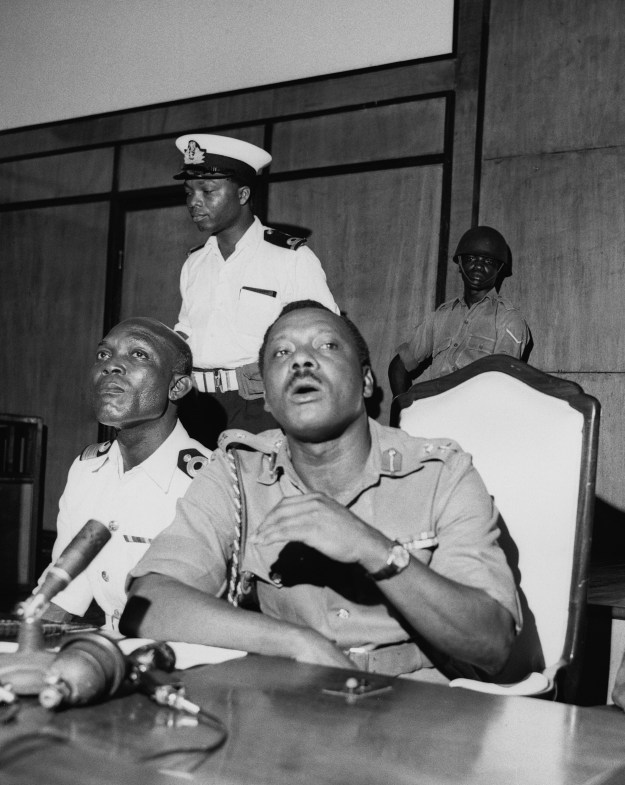

There was a countercoup just seven months after the first, fueled by revenge and led by northern military officers. The campaign killed hundreds of southern military officers, mostly Igbos and including Maj. Gen. Aguiyi-Ironsi. Lieutenant Colonel Yakubu Gowon became the new leader. In the months preceding the countercoup and then after, northerners led by military officers launched a systematic ethnic-cleansing campaign, in which the Igbos living in the northern region were killed. The statistics on exactly how many people were killed is contested to the day. It is estimated that between 3,000 to 30,000 Igbos were killed. These massacres were mostly ignored by the Gowon-led government. There were no trials for those who committed the killings.

By now the country was on the precipice of war. An attempt for peace talks was made in January 1967, when representatives of the Nigerian military government and the eastern region met in Aburi, Ghana, to discuss a resolution. No agreement was made.

Seven months later, Col. Ojukwu declared the eastern region, to be called Biafra, an independent nation. On July 6, 1967, the Biafran War commenced.

What followed was three years of armed conflict that shocked the world with its extreme violation of human rights, spawning the creation of international organizations like Médecins Sans Frontières. Nigeria blockaded all transportation routes into Biafra, starving millions and leaving children malnourished. Biafra briefly took control of oil facilities in Port Harcourt, killing foreign nationals in the process. Nigerians massacred ethnic minorities in Biafra, most gruesomely in Asaba, where the victims were unarmed civilian men and boys. The war ended in 1970 with Biafra’s surrender. To date there has been no reconciliation, nor has the Nigerian state shown any sign of learning from history or the legacy of the war it fought.

The Biafran War is conspicuously absent from the curriculum of the country’s educational system. In November 2016, the legislature rejected legislation to make history a compulsory school subject. Most people learn about the war through stories passed down by their grandparents, vague footnotes buried in political science textbooks, or more recently Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s award-winning novel Half of a Yellow Sun.

Yet a particular group—the Igbos—have not forgotten this history. How could they? They remain politically marginalized. The highest political office an Igbo citizen has held since Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999 is that of senate president, elected by fellow legislators in the National Assembly. Power has mostly rotated between the north and the west and briefly to the minority South-South (not part of the breakaway region) when President Goodluck Jonathan was in power. There is no federal infrastructure—such as highways and roads that would aid in the transport of goods and people—in the east as there is in the other regions.

This has fueled the echoing of secessionist calls. Spearheading the calls is a British-Nigerian political activist, Nnamdi Kanu, who has resuscitated Radio Biafra—last used during the war—to spread his message. He is one of the founding members of a separatist organization, the Indigenous People of Biafra.

He has frequently been detained and harassed by the Nigerian government. He is currently missing, after an alleged raid by the Nigerian Army at his home. The military denies Kanu’s brother’s claim that he witnessed the raid.

On Jan. 15, 1970, in a radio-broadcast speech announcing Nigeria’s victory over Biafra, then-Lt. Col. Gowon declared, “The so-called ‘rising sun of Biafra’ is set forever.”

Fifty years later it remains to be seen if this is the last word.