The hunt for a perfect taco is a deeply Angeleno pursuit, and as a native son of L.A., I am no stranger to the thrill of the chase. But La Reyna’s al pastor taco—a rumored downtown masterpiece of slow-cooked pork, cilantro and spice—is eluding me completely.

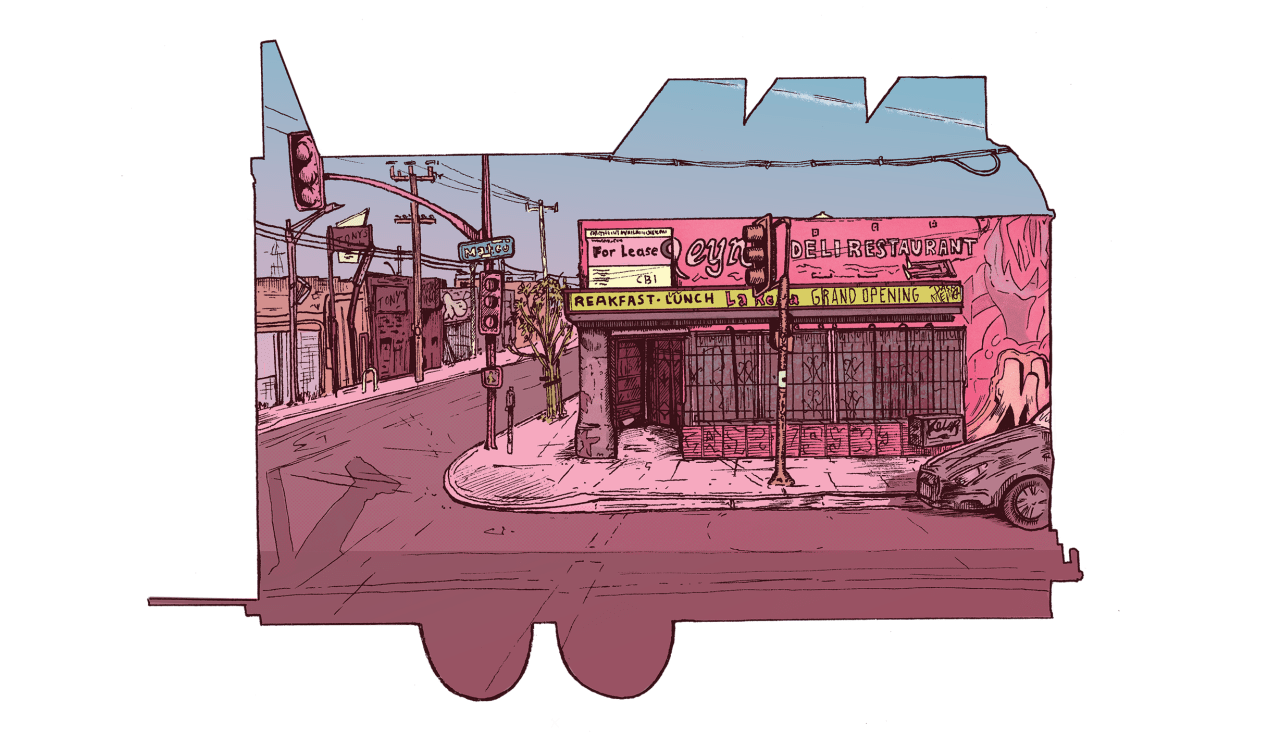

Part of the problem is the velocity of gentrification in Los Angeles. I know that Anthony Bourdain visited La Reyna, a downtown institution on the corner of 7th and Mateo, for Parts Unknown in November 2016. By Christmastime, the restaurant was shuttered and the cooks were serving their tacos from a grill on the sidewalk out front. By the time I picked up the trail in March 2017, some online reviews suggested that the sidewalk grill was gone, at least some of the time, and instead a taco truck had taken its place.

So I have come in person to the Arts District, the rapidly gentrifying triangle of warehouses, homeless encampments and upscale galleries, squeezed between downtown and the LA River, to see how, where—and even if—the La Reyna taco lives on.

I head straight to the corner of 7th St and Mateo, where the corner restaurant is still shuttered, and look for a grill, or a truck, or a cart, or a cooler. It’s around 4 p.m. on a Wednesday, and there’s nothing here. I start asking questions.

A blonde woman at a nail salon around the corner—she also sells artisanal beverages, assorted essential oils, and Wiccan goods—says she hasn’t seen the truck in a while. The truck was orange with white trim, adds a young man with painted nails and an eclectic array of pins on his jean jacket.

I walk to a chic restaurant blocks away, but the waitress there says something completely different—she claims there was never an orange truck with white trim; it had only been the roadside stand.

I walk back toward La Reyna. It looks a lot like Williamsburg in this part of Los Angeles. Water towers, industrial spaces with rusty piping and crumbling brick. And a parade of beards, well-trimmed and well-oiled. But no taco truck. The Arts District had been an industrial zone in the early 20th century, hence the warehouses. As early as the 70s, it began reinventing itself with spaces for musicians and other artists.

The gentrification story here is a bit different than nearby examples in LA. This isn’t, as is Boyle Heights across the river, a long-established immigrant community beset by wealthy white people pretending to rough it. But when the real estate developers came here with lofts and artisanal coffee shops, when the struggling artists became well-to-do struggling artists, they still displaced older businesses. Perhaps they also displaced my taco.

Patrick Salway, 28, is the manager of Pizzanista!, a pizzeria across the street from the space formerly known as La Reyna. Salway, long-haired and wearing a jean jacket with a Rolling Stones lips pin—he describes his look as “more Keith Richards than Jim Morrison”—has been frequenting this area for a decade, at first to practice with his band at a studio here.

Salway seems surprised I’m asking about La Reyna. “It just seemed like kind of a forgotten place.” But it was a community stalwart, he admits, that did seem to draw some visitors from out of town.

David Bowie’s China Girl plays in the background.

Salway has been eating at La Reyna—at first carne asada, and then a veggie burrito since he became a vegetarian—for a decade and is sad to see the restaurant close. But for him, the gentrification isn’t all bad. “When I started working here there was nothing other than La Reyna on this street—I think I’ve witnessed the changes firsthand. I feel fortunate to be part of the changing landscape here,” he says. “This area is going through a gentrification process. You can’t deny it. I don’t feel guilty, but I’m part of it, I’m here.”

In the Arts District, change is the only constant, according to Salway. In the six years he’s been at Pizzanista!, he’s seen a single retail space across the street transform into a “weed clinic, then an art gallery, then a clothing line that didn’t stay very long.” And that’s just in this relatively desolate corner of the Arts District, right before the 7th Street Bridge leads into East LA.

A few blocks away, there’s more happening: A French bistro—a well-lit interior, with tall ceilings—called Church & State. Jonathan Ortega, 20, is a dishwasher there and soon-to-be prep cook. He’s sitting outside with a plate of food for dinner.

Every Friday, he says, the restaurant workers would send him “with a big list” to La Reyna. Since the restaurant closed, it’s been tough for Ortega, who used to get the chorizo burrito. “It kills me, man, it does. Now I have to take my food pleasures… my food desires… elsewhere.”

Pure poetry, but still not any kind of indication of where the truck might be.

I wander back toward La Reyna again. Just outside the closed restaurant, a man with glazed, bloodshot eyes paces frenetically. I loop around the block. As I pass the man again, I smile and nod. “Faggot,” he mutters, and then again more loudly. He reaches into his pocket. I assume the worst—maybe it’s a gun, and I’ll have lost my life reporting a story about tacos. But no, it’s a phone, and Massoud lives to see another day. The man proceeds to take photos of the “faggot,” to what end is unclear, but God bless.

After the man finally leaves and I return to what had been La Reyna, I find Aaron Moreno, 32, standing outside the business, dumbfounded. He has long hair and a beard. He’s wearing a “Dump Trump” sticker. Moreno is a musician and mixing engineer of Mexican descent from Orange County, who has been living about a mile away for nearly five years and been coming to La Reyna for solid Mexican fare the entire time.

“It was crazy cheap, and I tried it and it was the best Mexican food on this side” of the bridge into Boyle Heights. “The gentrification is running rampant,” Moreno says, noting that this place was always a bit empty. But he fears that what’s happened to La Reyna will repeat itself in nearby Boyle Heights, where real estate developers are said to have set their gazes, much to the chagrin of many Angelenos.

Down a nearby alleyway, there’s an encampment of people living under tents and tarps. But in another side street, there’s also a restaurant—The Springs—a “hub of wellness” that looks like a Brooklyn greenhouse.

They’re going to shoot a Honda commercial around the corner, according to a filming notice posted on buildings. The Lichas Santa Fe restaurant and bar down the street from La Reyna looks at first like it might be a still-operating Mexican-American watering hole. The door is open, so I wander in, but nothing—a dark, unadorned space in need of a dusting—and no one is inside. On the chainlink fence in the back is an advertisement for film industry folk looking for spaces to film. A location scout pokes his head in. He’s flanked by other industry types.

Oliver Ryan, 27, works at Silverlake Wine Arts District, a branch of a local wine seller that opened across the street from La Reyna over a year ago. He used to get the carne asada tacos with salsa verde. Ryan is a non-Latino Angeleno who has Canadian and British citizenships.

“To see the nervous system of a culture get just ripped out on rising rent and at the same time have this other axis of pressure coming from immigration policies or whatever—it’s sad,” Ryan said. He adds that he thinks the closure had nothing “to do with them being Hispanic, but you’ll see the demographic down here is dramatically changing.”

Ryan, who is wearing a Farrah Fawcett t-shirt, is speaking to me from the spacious wine cellar in between sales. Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy” played in the background.

“There are a lot of four letter words you could use to describe it, but it’s sad.”

A young man appears out front of the old La Reyna at around 6:15 p.m., as the sun sets. He’s waiting for something.

Moments later, a large taco truck appears. LA REYNA TACOS #2, it announces on a hand-painted sign across the marquee. A portrait of the Virgin Mary adorns the door to the kitchen in the truck bed. The truck is here. I am delighted.

The young man, Dennis Palacios, 17, had been waiting for his after-school job. He hops in and takes orders.

There are two other men working here—Daniel Avila and Eduardo Ramirez, both 29. Wages haven’t changed since the closure just a few months ago. And none plan to abandon their posts, as long as the owner of La Reyna will have them.

Keeping the truck present on the same street corner as their former restaurant, they say, is about laying claim to a rapidly changing neighborhood that’s “been modernized. It’s become like New York,” Ramirez said.

“We aren’t going to give up just because we got kicked out,” says Ramirez, who has worked at La Reyna for nine years.

“If they stayed we’d have had to raise the food prices. A lot of people wouldn’t even want to pay [higher] prices for the food,” Ramirez adds.

They can only speak briefly before a small crowd begins to gather for tacos and more Americanized treats like burritos. Robert Penna, 27, is an American of Argentine origin who had been coming to the restaurant for two or three years. He drives about 10 miles from Monterey Park, where he lives, for the asada burrito.

“It’s one of my favorite spots,” he says. In just a matter of minutes, he sits down on a foldout chair on the sidewalk, inhales a decent-sized burrito, and leaves before the roads become clogged with L.A. commuters.

Many others order the mulitas—a meat and cheese sandwich. Some order it with beef or pork, others with cabeza (cow cheek and meat from other parts of the head) and lengua (beef tongue). Two mulitas run customers $5, which is, relatively speaking, a bargain in a part of town suddenly dotted with high-brow dining establishments.

I sense an opportunity, and finally order my tacos. The meat is delicately seasoned, succulent and tangy. Well worth the long chase.

It would be a few more days before I am able to track down La Reyna’s owner Juan Mendieta, 46, by phone to get his story about what actually happened to his restaurant. He started the business about 17 years ago, and business had been doing fine, until he got a notice from Borra Lafond, the company that owns the building, saying La Reyna had to vacate. “I said I want to stay here, and [the Borra Lafond representative] said, ‘No, I have another plan,’” Mendieta says.

“I told them, ‘I just want to work. Give me a chance, I can work.’ But they didn’t even tell me how much they want.”

After the store was closed, a “For Rent” sign went up. A friend of Mendieta called Borra Lafond’s offices to ask how much it would cost to lease the space for a new Mexican restaurant. Mendieta says the person who answered the phone quoted them $17,000 a month—several times what Mendieta had been paying.

“I want to stay there. But if they don’t want me there, what can I do? Nothing. I can stay for a few months, but that’s not the point,” Mendieta says.

I have reached out to multiple parties identified as owners or associates of Borra Lafond, but none have responded at time of publication. The real estate agents for the space haven’t responded to calls and emails.

Still, for La Reyna cook Eduardo Ramirez, it’s relationships with patrons like Penna that are the constant in a neighborhood and business in flux. “The same customers are still coming,” he says. “They just have to recognize it’s us.”