Clayton Patterson has been photographing New York’s Lower East Side since the early 1980s. His images reflect both the unrest and the chaos that gripped the community in the 1980s and 1990s as well as the beauty and diversity of the people who lived there during those years. Patterson’s archive is raw and real, a record of a neighborhood that has undergone drastic change in recent years. Explore Parts Unknown’s Cengiz Yar spoke with Patterson about his work and the neighborhood that has inspired it.

Cengiz Yar: What was the Lower East Side like in the 1980s?

Clayton Patterson: It was like a war zone. The night we moved in, in 1983, a guy got shot across the street. That was a “welcome to the neighborhood” kind of moment.

There were bonfires on Avenue A so big the buses couldn’t pass. The cops and the people threw bottles at each other—whole streets would be covered in hundreds of bottles. I saw people get shot, stabbed, beaten, all kinds of things. It was also one of the most notorious drug neighborhoods in the world, because it was connected to all the bridges and the Holland Tunnel.

But it was also very affordable. It was a mixed community, with Hispanics, blacks, Jews, and artists. It was near Wall Street, so you had all of these different people coming down here and buying drugs.

So there was an element of danger and street life which I was really interested in.

Yar: How did you go about photographing people?

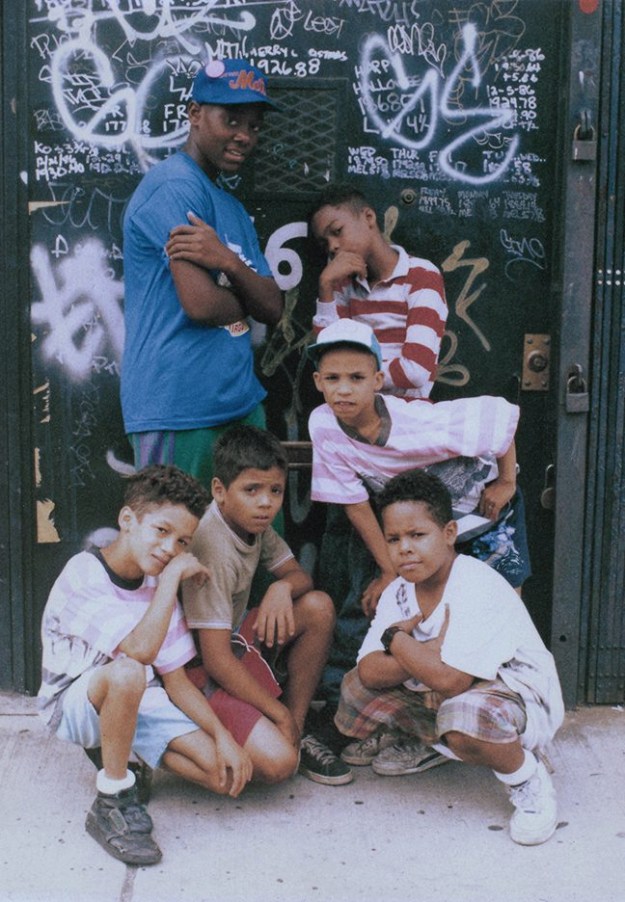

Patterson: I would take pictures of people hanging out at the front door of my building a lot—it was often neighborhood kids. I got to know the drug dealers and a lot of the “dangerous people” in the neighborhood by taking their pictures. Then I would get these 3 ½-by-5-inch prints and put them on display in my window for everyone to see, like a gallery.

I photographed kids as they grew up. They loved to come by and see their picture in the window. It was always important for me to make it fun, so just before I would take their picture, I’d say something to shock them, like [tell them to swear]. I would snap the photo just as they cracked a smile. I did this because I didn’t want to create a situation where someone looked harder than someone else, or else all of a sudden we would have had fights. My door was neutral territory.

Some of those kids went on to get jobs in the computer world, some became DJs, and some of them murdered people.

Yar: The neighborhood has changed a lot since then. Do you still like documenting it?

Patterson: The thing is, it’s always changing. Now I’m kind of playing the end game. I still have the passion and love for it, but now I’m also interested in doing books. I’m working on a tattoo history of New York now.

Yar: How has photography changed since you got started?

Patterson: There’s so much documentation now. I’m a fan of looking at work on Facebook—there are some extraordinary photographers out there.

It still has magic to it. I think it’s just like cooking. Some people can snap that image into place and make it happen, and 90 percent of people can’t.

Yar: You work in a lot of mediums, including etching, drawing, sculpture, and documentary film. Do you consider yourself primarily a photographer?

Patterson: I don’t consider myself a photographer. I’m a guy who takes pictures, and in the end I think I’ll eventually make my mark in the photography world. But I’m just a guy who takes pictures. Richard Avedon is a photographer. I’m not him.

I’m pretty famous for my wild style and coverage of the [1988 Tompkins Square] riots. It’s not about being the most gifted photographer in the world—what you’ve got to have is passion. You have to show up, and you have to do it.

Yar: Did you have any big confrontations when you were shooting?

Patterson: My biggest confrontations were always with the cops. I got arrested like 13 times, had teeth knocked out, was knocked unconscious. But I never did hate the police or anything. I was doing my thing; they were doing their thing.

For us to be fighting against each other in a way is stupid, because they’re not benefiting from [gentrification] either. I know that their view of what we’re doing is totally different, and they have a view of society that’s different than mine; but the end result is that there’s no place for them, either. We’re all working class. It’s unfortunate we’re fighting against each other. I understand the ideological differences, but the reality is that they’re working class just like everybody else.

Yar: How would you describe the neighborhood now?

Patterson: Bloomberg brought in this corporate world. Now you have 7-Elevens, Dunkin Donuts, Starbucks, Target, Kmart—all of these big corporate entities that forced out family-owned businesses. Now the only businesses that can survive in this neighborhood are bars, and it’s just a drunken mess here every weekend. The streets are filled with kids of privilege—a lot of times white—just drunk and puking their guts out on the street. If you want to see Brett Kavanaugh in his youth, come down here.

Yar: This neighborhood used to be known as a haven for artists. How has that changed?

Patterson: You can no longer come here and be an artist. If you want to be an artist nowadays, you’ve got to have three jobs and do art on the side—if you’re lucky.

Back then you could work two nights in a bar and have enough time and money to work on your own projects. And so many creative people came out of that period. I lived the American dream. I mean, for who I wanted to be in life, I lived it. I had that in New York.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.