In 2007 Seattle label Light in the Attic Records reissued the first two solo albums by Betty Davis, a Carolina-born, Pittsburgh-raised R&B singer whose 1970s releases and live performances pushed every envelope. Her lyrics were suggestive, her vocals wild and aggressive, and while she’d been on top of the world for a time—associating with the biggest names in rock and jazz in the late ’60s and early ’70s—she’d also made more than a few enemies, facing boycotts and pickets from groups ranging from religious groups to the NAACP. By 1980 she had virtually disappeared, moving back to the Pittsburgh area and never releasing new music again.

When those records were reissued, Danielle Maggio was paying attention. The Pittsburgh-area native, now a Ph.D. candidate in ethnomusicology at the University of Pittsburgh, became enamored of the onetime Pittsburgher who turned so many rock tropes on their ears. Davis became a topic of discussion in the classes she taught, and eventually, Maggio signed on as a production assistant for the forthcoming documentary Betty—They Say I’m Different. Through her work on the film, she has gotten to know Davis personally, though she is famously withdrawn since her departure from the public eye. She has only given a handful of interviews, but she is involved with the documentary.

The film will premiere at the International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam, taking place Nov. 15–22, and it will get a Pittsburgh premiere thereafter. In advance of the documentary’s release, Maggio spoke with us about Betty Davis’s musical influence, her contribution to feminism, and her time in Pittsburgh.

Andy Mulkerin: What was Betty Davis’s original connection to Pittsburgh?

Danielle Maggio: She was born [as Betty Mabry] on a farm in North Carolina, and her father was in the service. When he got back from the war, he got work in the steel mills; and when Betty was 8 or 9 years old, they moved up to Pittsburgh, to [the steel-mill suburb] Homestead. She lived in Homestead from the time she was 9 until she graduated from Homestead High School. She continued to go back and visit her grandparents in North Carolina in the summers, work on the farm—which really is how the whole blues sensibility really stuck.

A lot of times when people talk about her voice and why she was so unaccepted in the industry, it’s because she doesn’t have that gospel, melisma, smooth, R&B, “black” sound. From what I understand, she didn’t grow up in the church, but she got her singing style from listening to her grandparents’ blues.

Mulkerin: An average person listening to Davis for the first time probably wouldn’t call her a blues singer per se. They might say soul or funk or something like that. But she does use the term blues a lot and name-drops blues artists in her lyrics and titles. What else makes her music blues?

Maggio: There are a few connections. The first is the types of songs she writes. All of her songs are first-person and they’re autobiographical, which is a very common thread among blues musicians—writing simple songs about everyday things: family, sex, pain, travel, loss. The timbre of her voice—that growling, that grittiness, that purrlike—that’s all from listening to blues records. And then her musical transmission—how she became a composer without being taught. Most blues musicians never read a lick of music, and neither did Betty. The way she wrote music and then taught it to the band—because she was essentially a bandleader—she would do it all by oral transmission and rhythmic cues. So I really think of Betty as a blues singer first and foremost. Even the way people talked about her was very much reminiscent of the classic blues women, who were talked about as overtly sexual and a kind of disgrace to their race at the time, this low-class music.

Mulkerin: Davis has a reputation for suggestive lyrics and overt sexuality in her music, which made it difficult for her to become a commercial success during her career. But if you think about what was going on socially and culturally at the time when she was coming up—it was the sexual revolution. Rock music and soul and funk were full of sexuality and double entendre. What was it about Davis that made that aspect of her music so difficult for people to take?

Maggio: There are a few differences between Betty and [other sexually suggestive pop] artists, especially the other black female artists. One is that she didn’t have any kind of male archetype with her. A lot of those women had a male bandleader, or they had a male manager, husband. She didn’t have a male leading figure. She was the main focal point of the show the whole time.

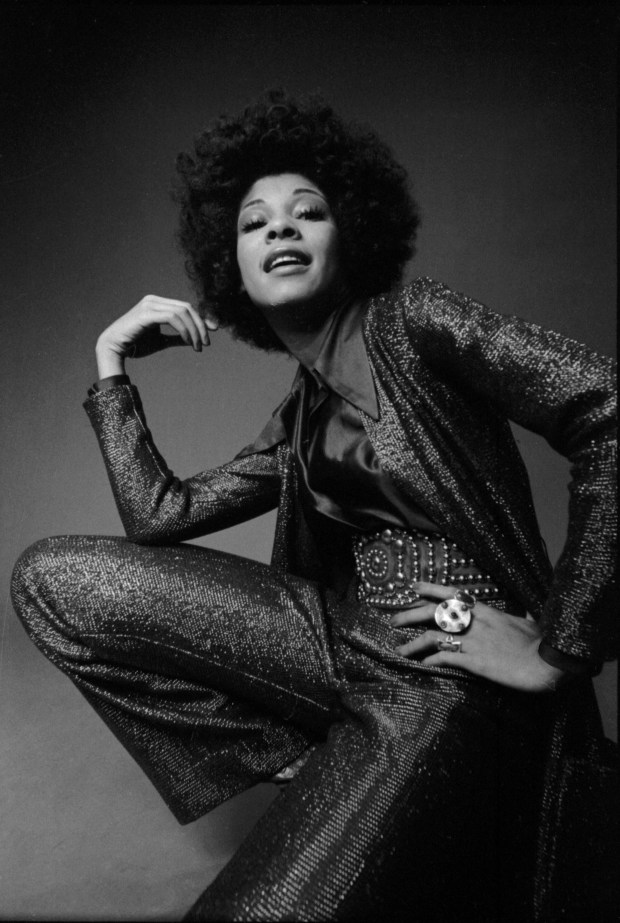

Another difference again goes back to the voice. Even [Tina Turner’s voice] still had that kind of gospel sound to it. Betty Davis was really proto-punk sounding. The fact that her voice did not fit what [some thought] a black, female body is supposed to sound like, I think, was really hard for people to handle. And then on top of that, what she did with her body. There are no live videos of her because she was far too suggestive, but there are pictures of her where her tongue is always out. In the song “Nasty Gal,” she even talks about how she can’t keep her tongue in her mouth. She would often use the mic as a phallic prop.

Her songs aren’t about pleasing men. Her songs are about her getting pleasure, or they’re about making men cry or be in pain. Her songs are so active; there’s no passivity in her lyrics. I think it was just too much raw black sexual femininity. People couldn’t handle it.

Mulkerin: Some of her lyrics could have been lifted straight from the past decade of feminism in terms of talking about what we’d now call “slut shaming,” what we’d now call “sex positivity.” How did that fit into the context of the feminism of the time?

Maggio: Betty will be the first one to tell you that she wasn’t a feminist. She didn’t think of herself as that, because she wasn’t politicized like that. Her body itself was political, but she didn’t have political ideology that was stemming this work.

The song “Anti Love Song” [talks] about giving in to pleasure. And in the song “He Was a Big Freak,” she essentially is naming off all these different roles that women play for men. So she’s giving a really amazing analysis of performativity—way before Judith Butler even started talking about that—and of sexual agency that was just not happening at the time.

Mulkerin: One aspect of Davis’s life that would click for many people who aren’t familiar with her would be her brief marriage to Miles Davis. How would you describe how they each affected one another artistically?

Maggio: People tend to talk about Betty as if marrying Miles was the most interesting thing about her life, and I completely think the opposite: I think that Miles marrying Betty for that year was the most interesting thing that happened in his life.

Any kind of biography you read or oral history on him, [Miles] was really nervous about getting stale and not being relevant anymore. So I really think he saw Betty and saw what she was, and I think he used her in a very specific and strategic way.

Betty introduced him to [Jimi] Hendrix, and he loved the wah-wah sound of the guitar; and that’s when he started hooking up the wah-wah pedal to his trumpet, started using distortion. So musically, that was the creation of jazz fusion.

Aesthetically, she threw out all of his Italian silk suits, loafers, took him shopping. Fashion was always a huge part of her, so she dressed him in a kind of youthful, psychedelic fashion, and Miles’ career just took [back] off from there. He pretty much is credited with reinventing jazz music [as jazz fusion], and there is only one or two quick mentions of Betty in any of his biographies.

Mulkerin: How does her music translate to students in an academic setting?

Maggio: Teaching about Betty at the University of Pittsburgh has been one of the coolest things, because most of them are freshmen or sophomores who are just taking the class to get credit and these kids were born in ’97, ’98, so they grew up with this extremely sexualized female “boss bitch” archetype as a pop star. And when I show them Betty Davis and they hear her, they still are affected by it. And that’s why I know she is so revolutionary: These young kids who are into Miley Cyrus and Beyoncé and Nicki Minaj and Peaches, they’re physically taken aback by the sounds and the images. And there aren’t even videos. Just her voice alone and this one snapshot image of her are so affecting. It made me realize how she resonates still today.

For more information on the documentary, visit the facebook page.