The early years of a professional photographer’s career are often a blur; harried, frantic, jumping from assignment to assignment trying to eke out a name for oneself. For better or for worse, most photographers run the gauntlet in their first few years, slowly creating and defining the style that becomes their distinct visual signature. Most of the time, these first assignments are forgotten (or hidden) as photographers refine their eye and move forward to bigger and better assignments.

It’s not often that one stumbles upon a master photographer’s earliest work, but that’s precisely my story. One day, immersed deep in the storage of a library’s back room, I found myself holding raw, unadorned negatives that Elliott Erwitt—now 89-years-old and a photographic legend—shot when he was just 22.

As a young photojournalist attending the University of Pittsburgh, I was enamored by the city’s rich photographic legacy. Margaret Bourke-White, Lewis Hine, W. Eugene Smith and plenty of other greats spent time documenting the Steel City. While listening to the police scanner and waiting for news to break as an intern at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, I would explore the locations—the exact street corners, bridges and buildings—where these photographers shot their iconic images.

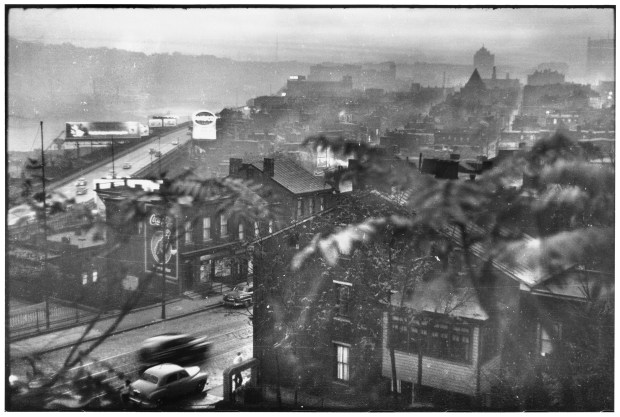

A very young Elliott Erwitt arrived in Pittsburgh in September 1950 at the invitation of esteemed picture editor Roy Stryker, known for his work cultivating the Farm Security Administration photography annals. Stryker gave Erwitt one of his first professional assignments as part of the newly-formed Pittsburgh Photographic Library (PPL). Once known for the smog of industry that choked out the sun at midday, city planners had their sights set on an ambitious project to, in the words of one newspaper report, “bring the first blade of grass to downtown.” Erwitt was simply told to document the city as it underwent a major civic transition, with no further instruction. The City of Bridges was to become a city transformed, and Erwitt (and the other PPL photographers) was to play a key role in shaping the public’s perception of the process.

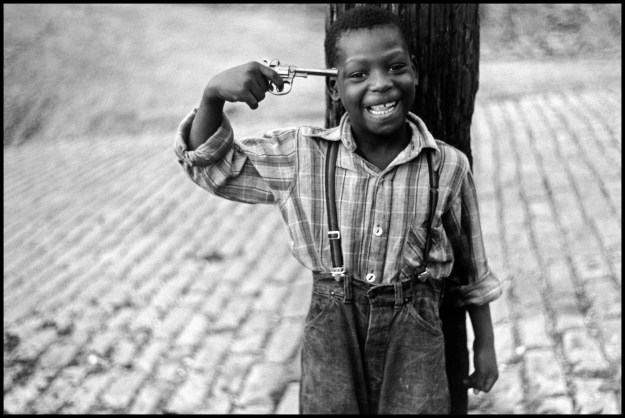

I had long been aware that Erwitt had spent time in Pittsburgh—one of his most famous pictures featuring a boy holding a toy gun to his head was captioned simply “Pittsburgh 1950.” Curious about his work in the city, I dug into Erwitt’s past, and I learned that the collection of PPL negatives was archived in the Pennsylvania Department of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, where it has resided since the 1960s. But for whatever reason, I discovered that his 500+ negatives from the project sat in storage with little fanfare, nestled amongst some 18,000 negatives in the PPL’s collection.

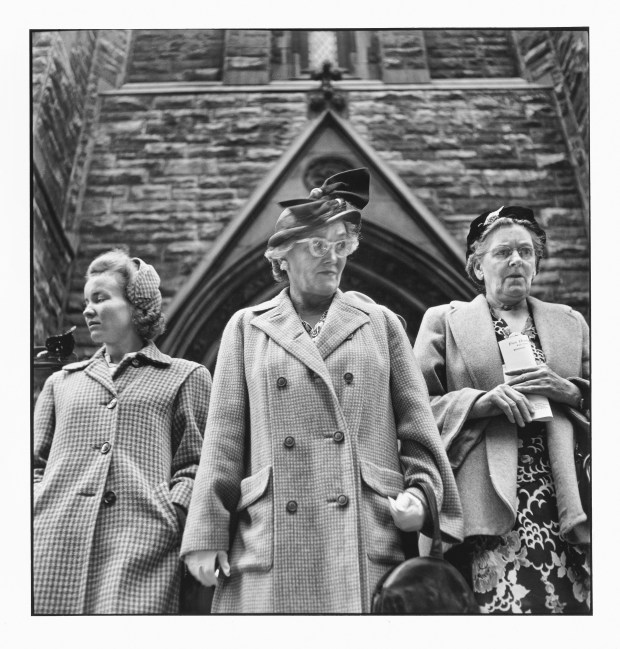

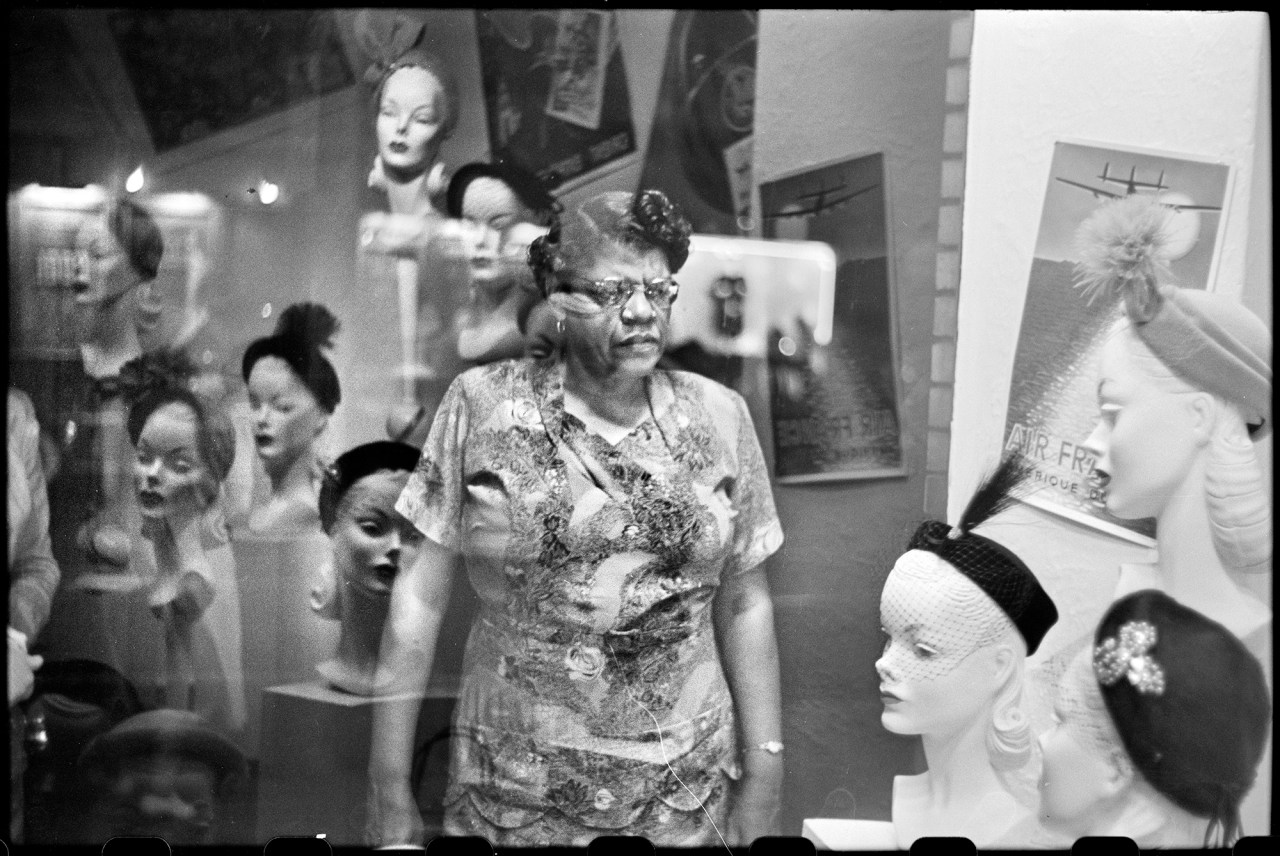

Erwitt’s work for PPL is quite diverse. Taking up a rented room in the downtown YMCA, he trawled the streets of Pittsburgh, photographing a litany of characters and locales. For weeks I pored over the individual frames of his contact sheets, tracing his steps through Pittsburgh. As a 22-year-old photographer myself, I was captivated by the young Erwitt’s eye upon my city and at the same time dejected; his photos of the city after only three months there were wittier, and had more voice, than my photos as an eight-year permanent resident. The energy visible even in his earliest work helped illuminate for me what my own photographs lacked (although isn’t this always true of the best poetry, prose, and art—that it helps us to see ourselves clearer in its shadow?).

Erwitt’s Pittsburgh negatives are magnanimous and deeply relational, reflecting his intensity of purpose as he wove through its crowds each day. His subjects’ gazes suggest a subtle acceptance of Erwitt’s brief intrusion into their lives.

After four months in Pittsburgh, Erwitt moved on from the city; an Army draft notice had finally caught up to him, and soon enough he was in Germany. I too left the city for New York after graduation, where one day I met Erwitt in person. Intent on hearing first-hand about his pictures I spent years studying, I arrived at his studio on Central Park West and asked him about Pittsburgh.

To my surprise, Erwitt had very little memory of his time in Pittsburgh and didn’t realize the library had preserved his entire assignment intact. I began ferrying them from the library to Erwitt on loan, where he and I sat and reviewed his work over the next four years. Sometimes he would pause upon a frame he quite liked; the delight on his face as he reviewed his own work after 67 years stays with me.

To Erwitt, Pittsburgh represents the first steps of his storied career. It’s where he carried out first extended professional assignment; a visually-rich place he cut his teeth. What is perhaps most remarkable is how his photos from Pittsburgh contains the same stylistic flourishes his fans have come to expect and love over his seven decades of work. Erwitt’s Pittsburgh pictures could easily mix with those he made decades later. It’s evident that Erwitt’s knack for quirky, human-driven moments was well-developed even as he was just starting out; his Pittsburgh photographs are some of his best (and thankfully not lost) work.

Vaughn Wallace is a Senior Photo Editor at National Geographic Magazine. He began researching the Pittsburgh Photographic Library in 2011 while completing his thesis at the University of Pittsburgh. Wallace has worked as a photo editor at Al Jazeera America and TIME Magazine and has served on the juries of World Press Photo, PDN Annual, and other competitions. He lives in Washington DC.

Pittsburgh 1950 is published by GOST Books and can be purchased here for $65.