In the Seattle episode of Parts Unknown, Anthony Bourdain goes to the Modernist Cuisine Cooking Lab, where he confesses to founder Nathan Myhrvold and executive chef Francisco Migoya, “I live in terror of bread.” Bourdain is treated to, among other things, bread in a jar (what?). Ahead of the publication of the new Modernist Bread series, Explore Parts Unknown editor Kaylee Hammonds chatted with Migoya about baking for beginners, deconstructing wheat bread, and what it’s like to have your dream job.

Explore Parts Unknown: I understand that you began your career as an art student. How did you come to food?

Francisco Migoya: I was debating in my younger years—much younger years—if I wanted to go to art school or cooking school. I was strongly leaning towards art school. It was a bit of a family conversation, [in] which I ended up being convinced that it would be best to go to cooking school and eventually be able to dedicate some of my time to artistic endeavors. And that’s what I’m doing now—I’m a chef, but in my free time I have a studio in my house and I paint and draw and sculpt.

That’s great.

I’m happy to be able to do both things—one of them pays the bills and one of them is more … personal.

I know that you spent some time teaching at the CIA [Culinary Institute of America], and I was wondering how that affected your approach to recipe development.

It definitely has. To give you more context for that, when I was teaching at the CIA, for eight of the nine years I was there I was in charge of a bakery/cafe that is open to the public in which the students are producing everything that is sold to real guests. In this bakery and cafe we would do not just pastry, we also did artisan breads and savory food—and we even did wedding cakes, we did ice cream, we did chocolates and confections. Pretty much everything. The challenge was that every three weeks I had a new group of students to do all these things. And any business’ nightmare is to lose all of your staff in one day and start with a brand-new staff. I got to do that every three weeks for eight years.

Wow.

In order to survive that, I had to make sure that all of my systems and recipes were supertight … so that the customers had no idea whether it was a brand-new staff or if our staff had been there for a while. It really positively influenced my recipe writing to put myself in the position of somebody who really has no idea how to make whatever it is that the recipe is about.

As you know, most recipes, most cookbooks, are written for best-case scenario: when you’re able to procure the ingredients, the exact weight and the exact amount of stuff, all the equipment necessary, it’s a perfect 70 degrees in your kitchen, and you have a fantastic oven that never breaks down. But that’s not life. Life is everything but perfect. So the way I learned to write recipes is to also consider the worst-case scenario.

There are points where once you [make a mistake and] you can’t go back, that’s when it’s a complete loss. But there are ways of preventing those mistakes from happening. I build a lot on that whole prevention side of things. I would say that [teaching] really made me pay attention to the details that people need to know.

It’s nice to know you’ve got our backs. Chef, can you tell me what brought you to Modernist Cuisine and how you got involved?

There was a point during my time at the CIA where I had already written three books, and I had read the Modernist Cuisine books. It was the sort of thing that I always fantasized about, being a co-author or helping to write in some regard if they ever thought about doing a baking and pastry book. So it was always one of those wishful-thinking moments that you think about while you’re sitting in traffic.

So I started to create an exit plan from my time at the CIA because I feel like nine years was enough. So I opened a little chocolate shop. If it was sustainable enough, that would provide for me to make a living off of it, and then I would leave the CIA.

However, plans changed because not even a year after I opened, I got a phone call from a recruiter from Modernist Cuisine. …I didn’t pick up the phone; they left a message. They asked, “We don’t know if you’ve heard of Modernist Cuisine, but Nathan is interested in talking to you about joining the team. If you’re interested, please call me back.”

Oh, my gosh!

And I could not believe that that had just happened, because it was everything I wanted to happen as far as employment went. I had this situation where I had invested a bunch of my money into this chocolate shop. But in my mind I knew that I had to make this work. So that same night I went to talk to my wife about it, and she said, “Of course the answer is yes.”

So then when I actually spoke to the recruiter on the phone, I just wanted to say, “Yes. Absolutely. When do I start?” But of course you have to do the dance, right? So that was the initial conversation. I met with Nathan in New York City. And a couple of months later I received an offer to come work as head chef for Modernist Cuisine. That was a glorious moment for me, because, like I said, it was one of those things that I had always wanted to happen, but … it didn’t seem like it was ever going to happen. And four years later this is the best job I have ever had. I don’t think it gets any better than this, to be honest.

What a great story. Moving on a little bit more specifically to the book—it is beautiful, by the way. Congratulations.

Thank you.

You did some 1,600 experiments during your time working on the book. Could you talk about one of your favorite successful experiments?

There’s a couple of them. … Let me pick maybe a technique that we developed for making light and open-crumb whole wheat breads. Typically if you use whole wheat flour in any bread, it’s typically going to be a very dense bread. All that bran and germ, they just weigh everything down. You have the delicious taste of the wheat bran and the germ and the flour, but it’s superdense. It’s not what you would consider a light and crusty loaf of bread.

So we took many paths to see if we could achieve it. It almost seemed unattainable. And then the one, the final path that we took that made it successful was actually separating everything. So if we had the flour, we would separate the bran and germ out, we would toast the bran and germ, we would soak that in a certain amount of water, and then we would incorporate that into the dough once the dough had developed. So we were basically bypassing all of the bad things that bran and germ does to dough—it is a volume killer, it is a water hoarder, it doesn’t work harmoniously with the flour, the endosperm part of the wheat. If you give it all it needs to stop doing that beforehand and you mix it into the dough once the dough has had a chance to develop itself, then you can have 100 percent whole wheat bread with a nice open-crumb structure.

So it’s pretty remarkable, because it’s not something we’ve ever seen done with bread before. It’s kind of like reverse engineering the grain to get it to behave like you want it to behave.

That’s amazing. I was going to ask you—and you don’t have to answer if you don’t want to—were there any experiments that didn’t work out so well?

Yes. I mean, if you have 1,600, there’s going to be some failures there.

That’s true. Any notable ones?

The failures occur because there’s a point where you have to think about whether something is worth pursuing further or not, whether it’s worth the time and money to find an answer to something.

But one of the ones that we are still mystified by is that when dough is fermenting, there’s a point where the yeast has fermented to its peak and so the dough is what is called officially “proofed” at this point.

That’s the moment where you put it into the oven. This is a very challenging aspect for most bakers, especially new bakers, which is to determine when this moment is. We had wanted from the beginning to develop either a technique or a piece of equipment, some sort of artifact, whether manual or electronic or digital, that would tell us, “OK, your dough is now ready to go into the oven.” It would kind of take that thinking or the expertise out of determining when this moment was. Because people worry, “Is it underproofed, is it overproofed, or is it just right?” We had so many different ideas, and we tested so many different things. Ultimately, what it came down to is that we weren’t able to resolve this.

It’s remarkable to me and humbling at the same time, because there are so many things in the science of bread that we have machines for that measure density, elasticity, all of these things … but still we haven’t been able to invent this machine that’s going to help determine proof.

I would say that that was one of the ones that I wish we would have had. I bet with enough money, we would be able to come up with something—with enough money and enough time.

Do you have any general advice for a beginning baker? Someone who’s kind of scared, like me, to make a loaf of bread for the first time?

Yes, I do. And I love that you ask that question because we do have answers for that, but I’m going to give you the short answer for it. … You’re going to need four things to successfully make bread in your home.

The first is get a scale, so you can weigh your ingredients. And then right after that, take all of your volume measures and throw them in the garbage or recycle them or give them to Goodwill. They serve no purpose—they are so imprecise. You want to have precision. That is your first wildcard there that could make everything fail. Volume measures—there’s no standard for volume measures. So buy a $20 scale. They’re cheap.

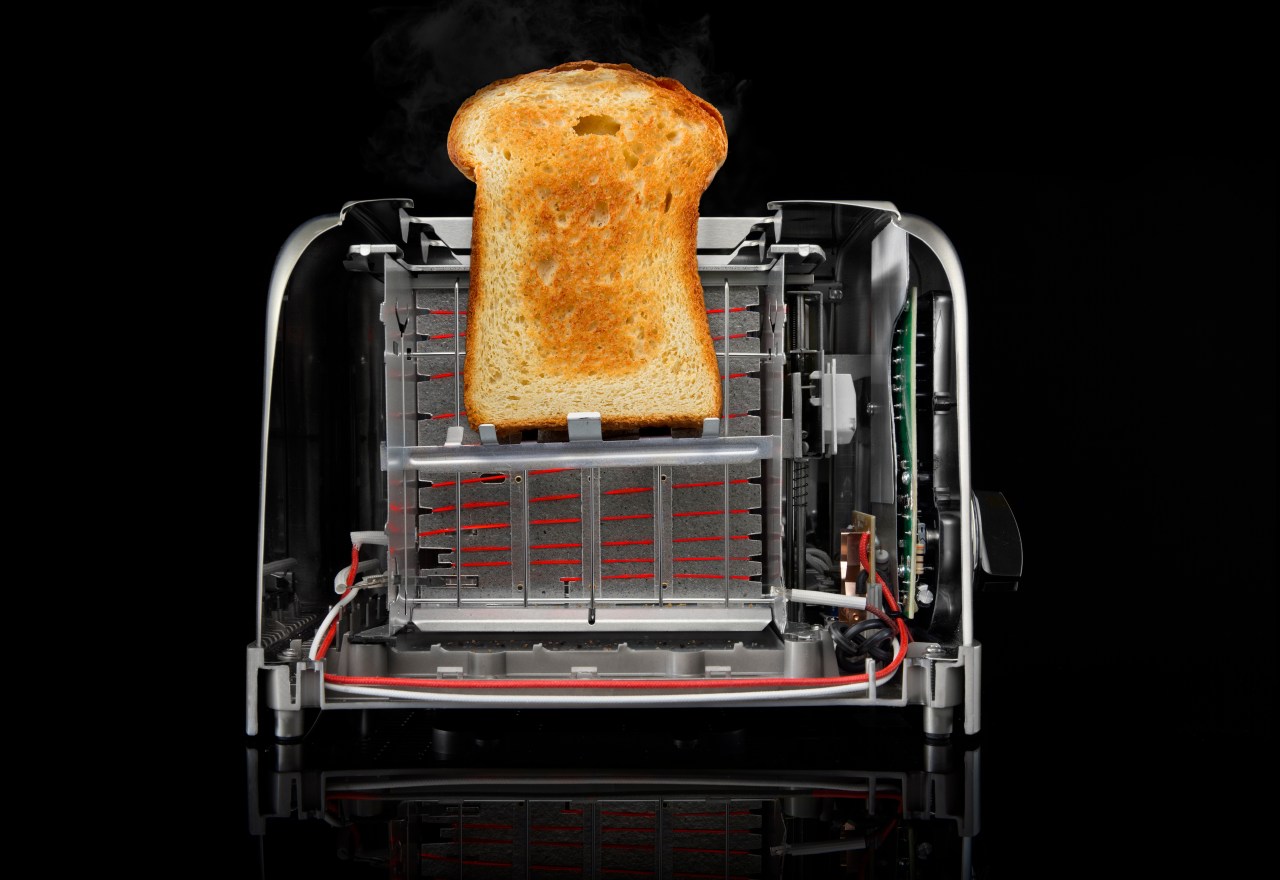

The second thing is get a thermometer … a digital thermometer. They’re also about $20. But a thermometer is going to be important for making bread because you need to know, when you’re mixing your water to your dough, that you do not have very cold water or very hot water. You want the water to be a certain temperature because that’s going to determine fermentation time and hydration and all of these things. But then the thermometer is something that you can use for everything else that you cook in your house. It’s multipurpose.

And then—this is something that is really going to help you make a good loaf of bread at home—it’s called a cast-iron combination cooker. … It has a skillet bottom and a deep pot, which is the top, although you can flip them over and then one is the top and the other one is the bottom. But we found that even if you have the worst home oven and you put this cast-iron combination cooker in it while it’s preheating, the cast iron is one of the best materials for absorbing heat but also radiating heat. It’s black, so that blackness really helps with radiation of heat but also absorption. We bake our breads inside these combination cookers.

So it’s the bottom part and the top part that seals the bread, the dough, into place, which also has another purpose: The dough creates its own steam. So you don’t have to spray water into your oven—you don’t have to do this thing that seems like sorcery to me. You just need to put your dough into the skillet, score it with a sharp blade, put the top on, and then just put it back into the oven. Set a timer. And once the timer goes off and you open the lid, you’re going to see this beautiful, crusty, deep, rich brown loaf of bread. And all you had to do was use a little bit of knowledge and technology and spend a little bit of money. These cast-iron combination cookers are around $40. [And] these cast-iron combination cookers, they can be used for everything else. You can make soup in them, you can cook eggs, sear your steaks—it’s multipurpose.

[And] you’re going to use the scale for everything else because you’ve committed to not using your volume measures anymore. So now you can have precision, and you can have consistent temperature radiating into your dough. Those are the things that are going to make for a successful loaf of bread.

We give in the different chapters … suggestions of what are the easier breads versus more advanced. So start with the easier ones. I would say, for example, our farmers bread is supereasy to make, and it’s delicious. There are many [recipes] in that realm, so start with those. And once you start getting comfortable and you start getting the feel for the dough and how it should feel and proofing, then you can get into the more advanced doughs. But take the time to read the recipe and start with the easier ones. Then you can up your game after you’ve made a few loaves and you feel more comfortable handling the dough.

I just had one last question for you. I know you love your job, but do you have a favorite thing? Is there something that you love the most about what you do?

I love the process. Not that I don’t love the finished product, but I think the process— It’s important to have that emotional attachment to getting through something. Because if you just want to hash things out, that’s how it’s going to look like in the end.

It’s almost a disappointment when the things are done and completed, because it means that that’s it for the process. But that is where I find the most amount of excitement and joy, from when things are getting done and happening. Because it all ends when you take the bread out of the oven and it cools down. That’s the end of the process. When you finish the recipe, it’s done. Then you have to move on to whatever’s next.

That’s really beautiful. I think people are too focused on just a ten-minute meal or getting things done—

Yeah. Even more so with bread. Because if you’re impatient with bread, it’s going to come out in the bread. That’s the way it is. It’s a living thing.