In a single generation, Singapore has managed to transform itself from a young, underdeveloped nation into one of the world’s most modern city-states. To the detriment of the thriving farming community in the ’60s and ’70s, however—with chicken, vegetable, coconut, pepper, rubber, and orchard farms and plantations—it now imports more than 90 percent of its fresh produce. Farming is no longer seen as an important economic sector for the country.

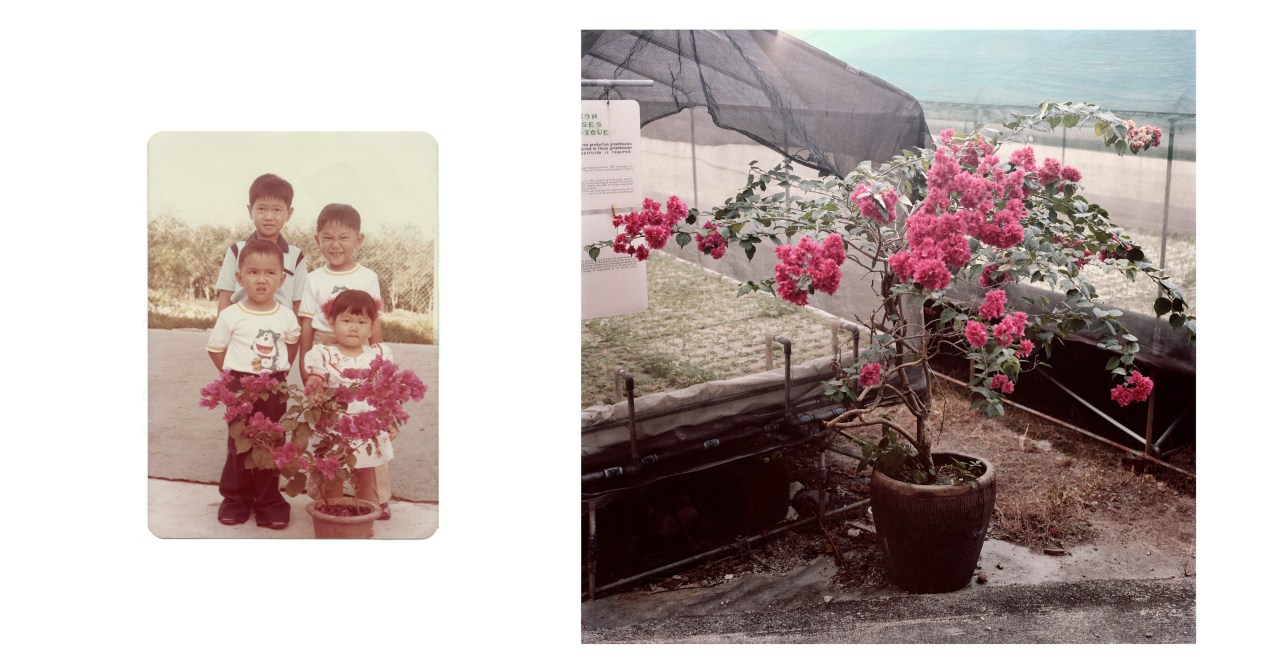

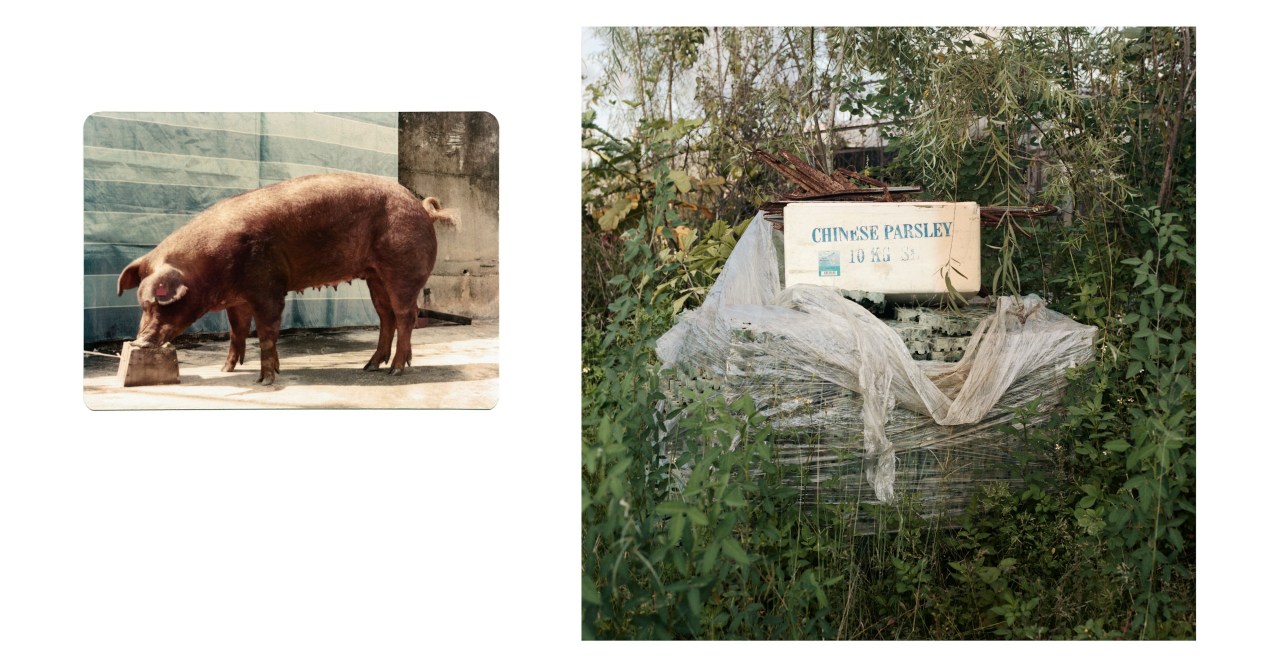

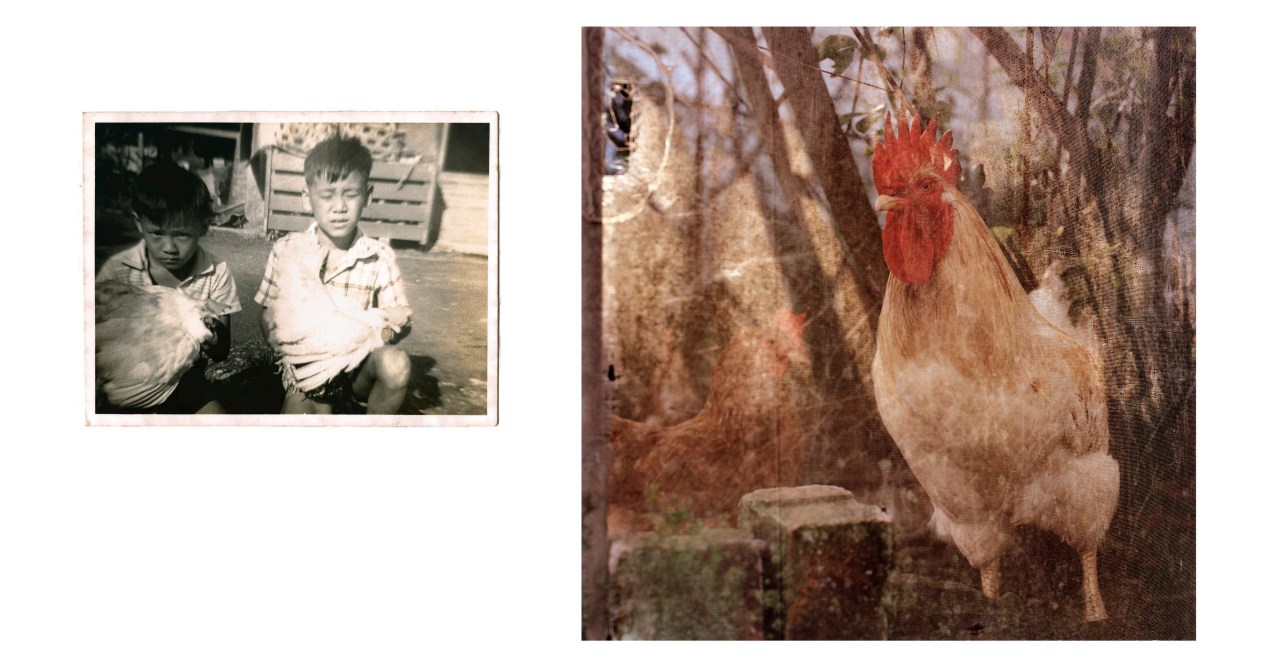

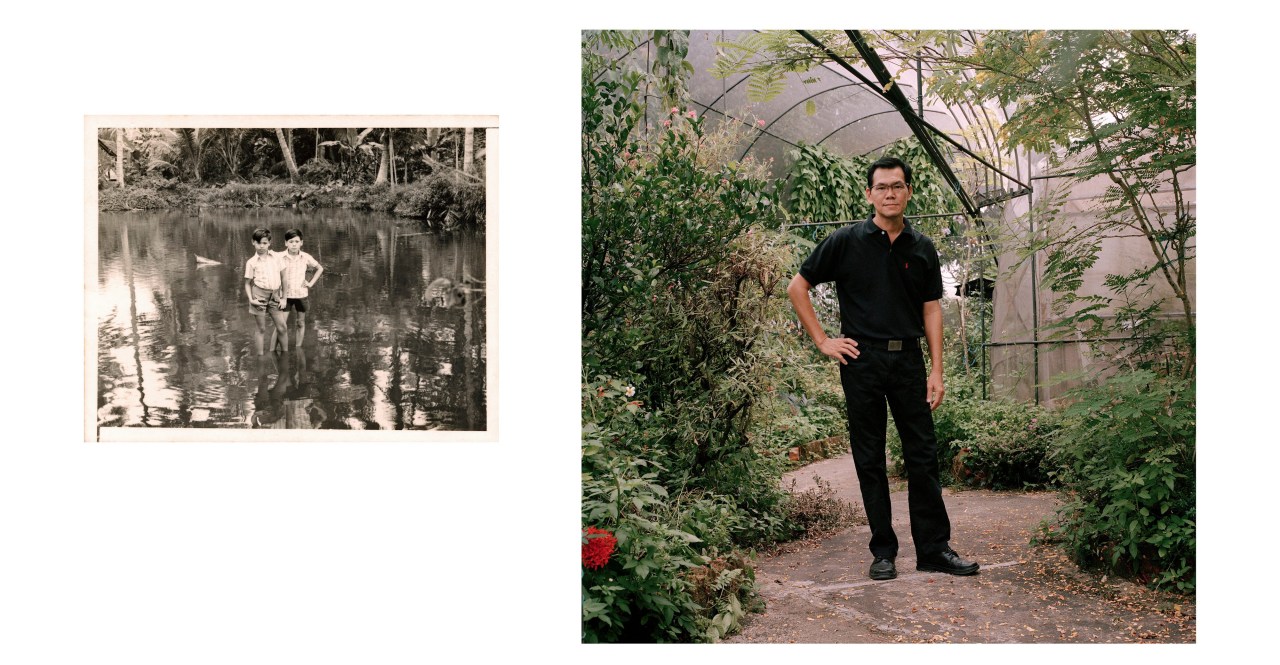

My family, three generations of farmers, has weathered these changes. In the 1960s my great-grandfather borrowed some money to buy a piece of land and start a coconut plantation in Yio Chu Kang. His seven sons worked alongside him. When his land was slated for redevelopment in the late 1970s, he moved his family to another neighborhood and started a pig farm. I grew up there, alongside roughly 100 members of my extended family who lived and worked together. My days of chasing piglets and exploring longkang [monsoon drains] came to an end in the late 1980s, when the government decided to phase out pig farming in Singapore. Pig farming required significant amounts of land and water, and the government wanted to develop the land. Many years later they built public housing where my family’s farm had been.

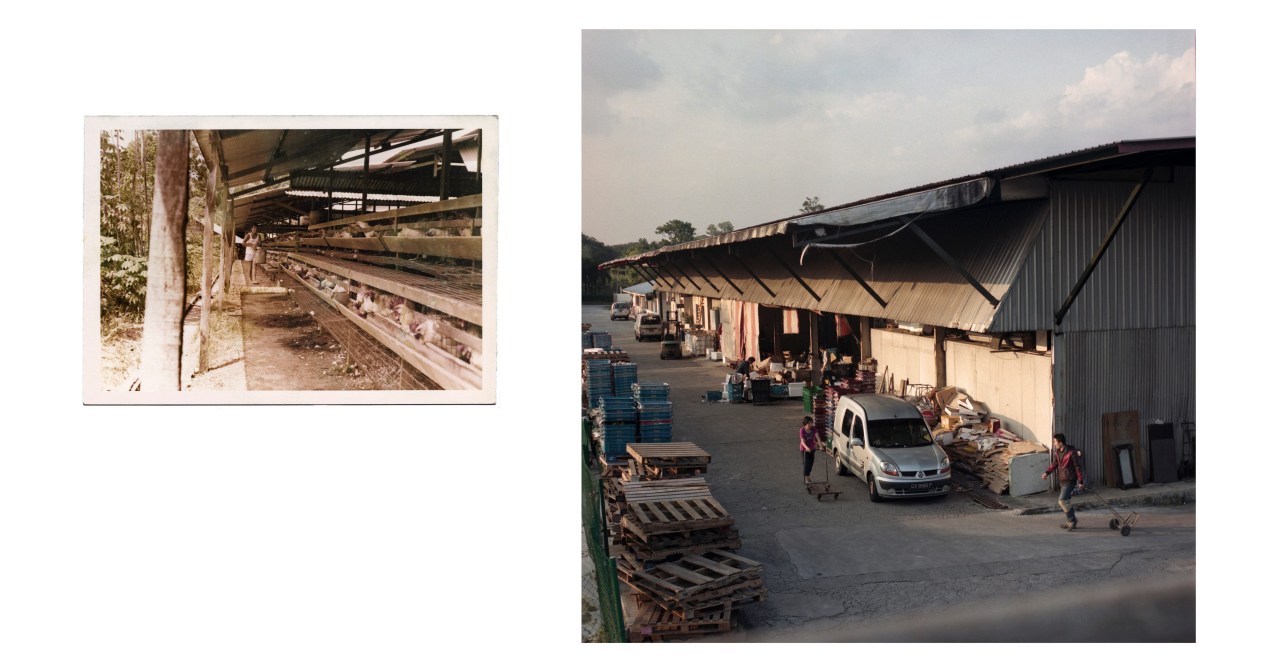

My extended family split up at that time. My great-uncles and their families went separate ways. My uncles and father went to Taiwan to study hydroponics farming and came back to build a farm from scratch. In the initial years they faced overwhelming challenges. Hydroponics (growing vegetables in water rather than soil) was a new concept in Singapore at that time, and they needed to create demand for their products. So they pushed on, often working seven days a week, and rested only on the first day of Chinese New Year. Failure was not an option for them: They had families to provide for.

After a period of struggle, things started to improve. My uncles and father ran the farm like a typical Chinese business, where the boss works alongside (and sometimes harder) than three dozen of his workers. Their work ethic was so strong that they rarely took a vacation. After 27 years, our farm, which sells leafy greens and herbs, has become one of the most successful vegetable farms in Singapore.

One of the key factors in our success is that it’s a family business, motivated not by profit but by kinship. This series of photographs is an exploration of that kinship, the hopes and dreams that tie us together, and a reflection of where my sense of self, community, and tradition comes from.

Every year the whole family would gather to celebrate my grandmother’s birthday, with the same mango sponge cake that she loved. Ever since she passed away, our family has not been the same.

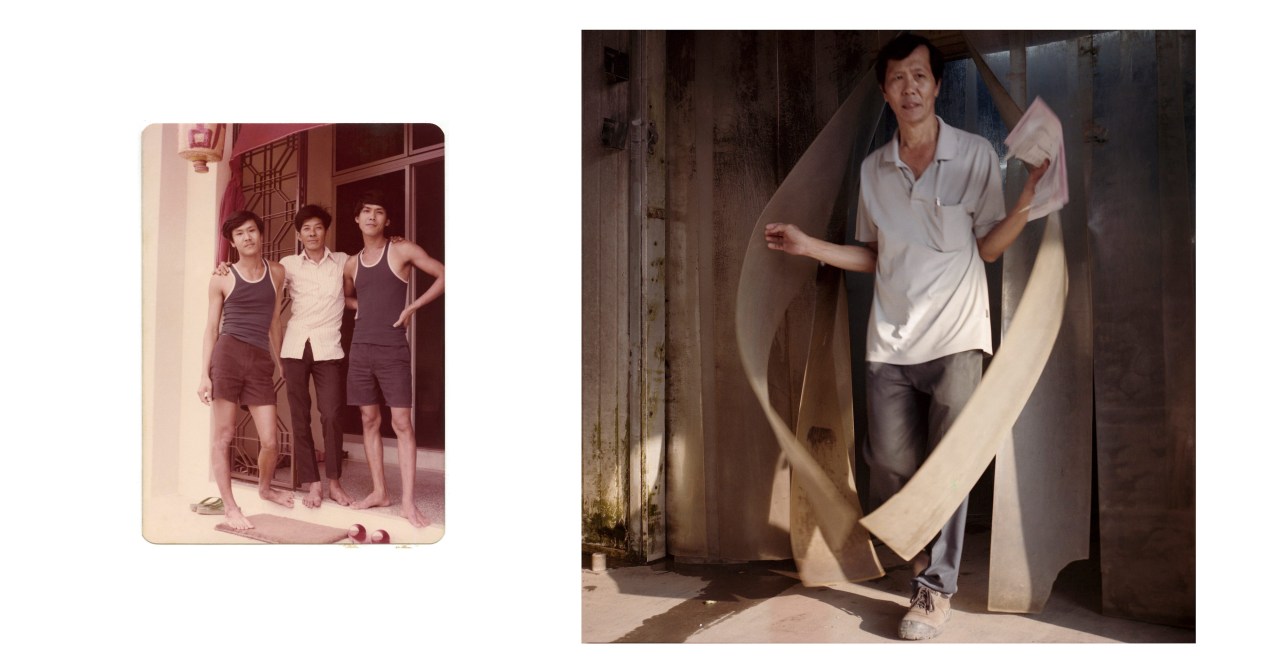

After our pig farm ended, all my grand uncles went their separate ways. My family chose to start a hydroponics farm so that we can stay together. Farming, because it’s what they know best.

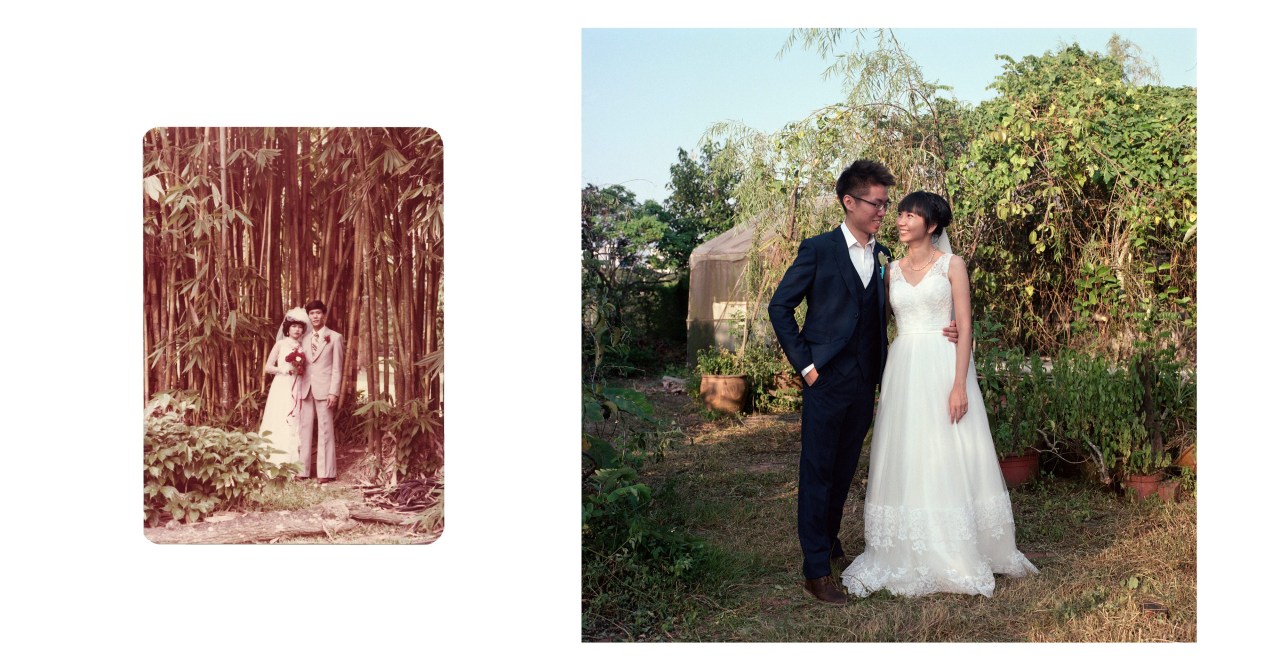

I always thought that I was different from my family; the idea of settling down felt so distant. Yet in the past few years I have felt a yearning to start my own family.

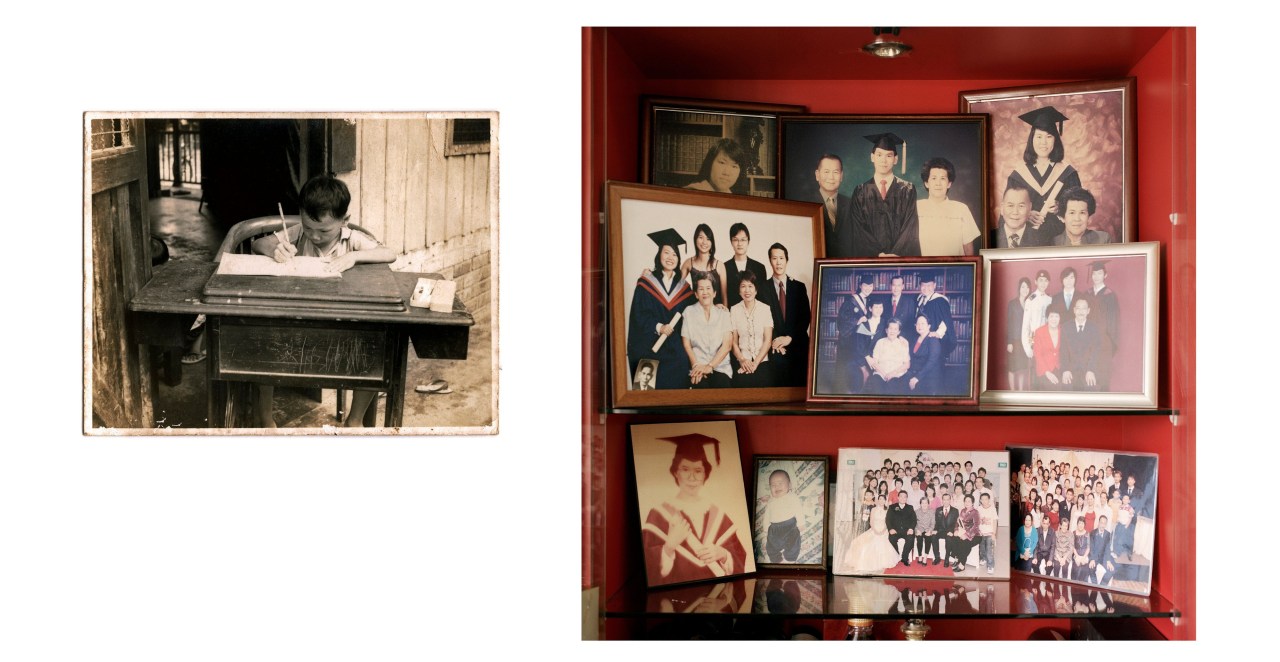

Education has always been important to my family. My youngest uncle was the first in the family to study abroad. After he graduated, he chose to return and help out in the family farm.

My grandmother was a traditional woman who believed that her fate in life was to work, live and take care of her family. She continued helping out at the farm until the last months of her life.