The 50-year-old man suffering from respiratory failure was in severe distress—short of breath and coughing up blood. Realizing he may have only hours to live, the village health assistant called 112, Bhutan’s emergency medical hotline. But reaching him wouldn’t be easy. He lived in a small, high-altitude village cradled by rock and trees.

“There was no road access, no place for us to make a safe landing, and he was deteriorating fast,” recalls Dr. Charles Haviland Mize, an American resuscitation specialist and the head of the Bhutan Emergency Aeromedical Retrieval (BEAR) team. “We feared he wouldn’t survive, were we to land and then try to hike 30 to 40 minutes to reach him.”

Instead, the team had its helicopter hover a short distance downhill from the patient. The pilot balanced on one landing skid at the edge of a small rocky field, keeping the other suspended in the air.

Mize and a nurse climbed uphill, hooked up the patient to an IV, and medicated him to ease his breathing. “My partner helped tie the patient to my back—fortunately for us, he weighed a scant 50-odd kilograms—and we climbed down with him, pulled him into the helicopter with the blades still running, closed the doors, locked him in, and set to work restoring his breathing as we lifted away from the mountain and fell into the open sky,” Mize says.

The man survived.

BEAR, which began operating in May 2017, is one of the world’s highest and most daring medical evacuation services. Working at elevations from about 900 feet to more than 14,000 feet, the team—typically a pilot, doctor, and nurse—work in often dangerous conditions, maneuvering through mountains in heavy rains and dodging crisscrossing electric wires.

There are many for-profit rescue services in the Himalayas that cater to wealthy clients and tourists, but Mize says none serve poor or middle-class patients. The Bhutanese government offers free universal health care, and BEAR charges patients nothing. As of May 2018, it has responded to 368 calls; 298 of its patients have survived.

Mize says he got the idea for the program in 2016, when he was volunteering at Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital, in Bhutan’s capital. A 14-year-old boy who had fallen from a roof was brought in. He’d been evacuated by helicopter but received only minimal treatment before arriving to the emergency room; Mize attempted to resuscitate the boy, who later died of his injuries. He later helped launch BEAR, in conjunction with the national referral hospital and the Royal Bhutan Helicopter Service Ltd., with the goal of delivering ICU-level emergency care to anyone anywhere in the country within an hour. (Mize is currently back in the U.S. but continues to work for BEAR remotely.)

Though expensive for a developing country, BEAR fits squarely into Bhutan’s development philosophy, which prioritizes gross national happiness over gross domestic product, and the program’s proponents say it can be a model for other developing nations with large rural and sometimes hard-to-reach populations.

BEAR works a bit like the 911 hotline in the United States. People call 112 and reach Bhutan’s emergency response center, which is at the National Referral Hospital. In cases of dire emergency, the dispatch team activates BEAR, and within minutes, a helicopter carrying a team of doctors and nurses takes off from a helipad in Thimphu.

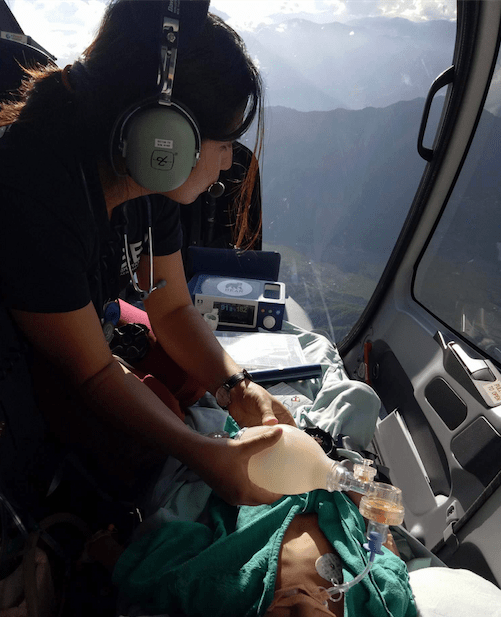

The team administers care on the ground and in the helicopter while relaying the patient’s condition to the hospital in Thimphu.

The program saves lives, but it comes at a cost. Through March of this year, the Ministry of Health has spent more than $2.1 million on the service, according to Health Minister Tandin Wanghuck. He is quick to add, “It is not fair to measure life against money. Even one life saved is worth every penny spent.” BEAR also receives additional funding from private donors and the Bhutan Foundation.

BEAR has three doctors and four nurses. Everyone must pass repeated strenuous physical fitness tests. “Setting off on retrieval missions isn’t easy,” says the program’s Dr. Sweta Giri. “Besides hiking uphill carrying heavy equipment [weighing up to 66 pounds] in the shortest time possible, we need to be able to jump off the chopper while the blades are still spinning.”

Dr. Sona Pradhan, head of the emergency department at the National Referral Hospital, says BEAR plans to expand by the end of the year so the current team may have reinforcement. Some days, the team members augment the staff of the emergency department. Other days, they are scattered across the country from dawn to dusk, inducing anesthesia in farmhouses, pulling the injured off mountains, and helping sick newborns breathe at some of the highest altitudes in the world.