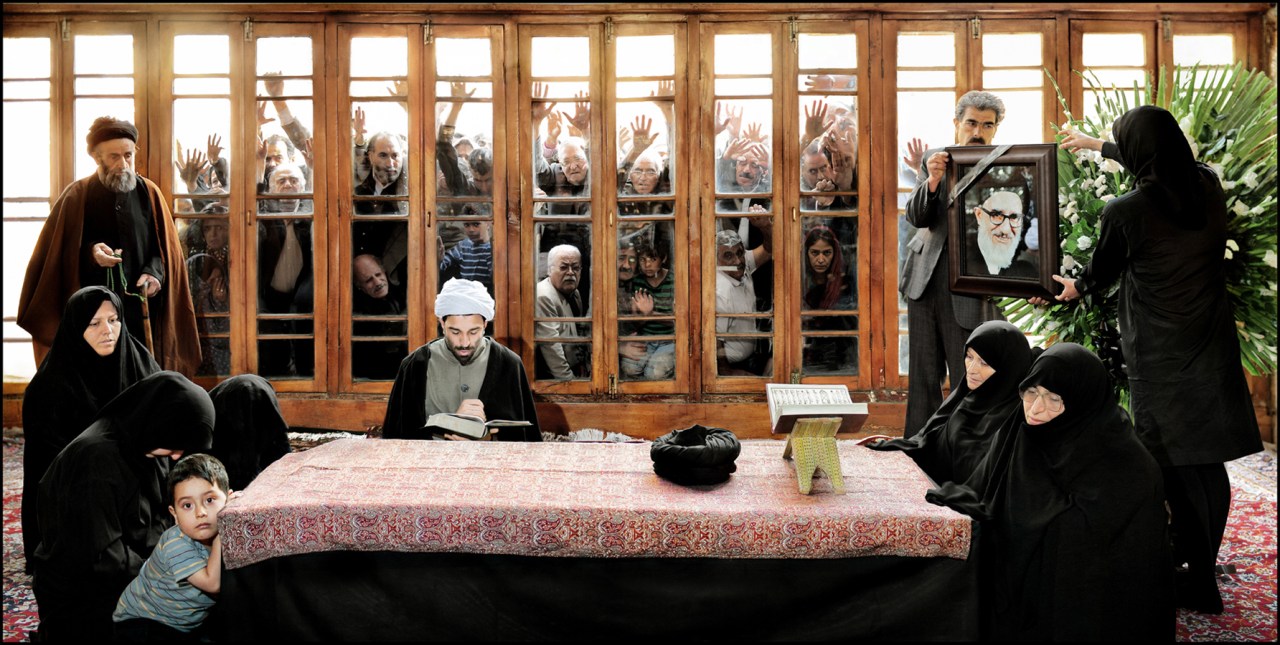

Look closely at these photographs and you might notice, in each one, the same woman in a red headscarf and black dress. That’s Azadeh Akhlaghi, the young photographer who researched, staged, and shot the images. The project, called “By An Eye-Witness,” is a dramatic reconstruction of 17 seminal deaths from Iranian history. It took Akhlaghi three years to research and select these events, from the revolutionary sociologist who died mysteriously after being released from solitary confinement to the student activist shot by the secret police. And though the images are highly cinematographic (Akhlaghi worked as an assistant director for years), as still photographs they remind me more of Renaissance religious art, the passions and agonies of the protagonists frozen in time. She spoke to me from Tehran.

Pauline Eiferman: How did the project start?

Azadeh Akhlaghi: It began with a political shock in the aftermath of post-election uprisings in Iran in 2009. I started to think about the revival of history. The death of Neda Agha-Soltan and many others, as well as the Arab Spring [affected me]. I followed the news, sitting behind my computer, looking at the photos of people in Cairo or Benghazi. Then I started to think about all the freedom fighters who died in heartbreaking circumstances.

Eiferman: Did you feel a personal connection?

Akhlaghi: Of course. When I thought about these people who decide to go to the streets knowing that they might be killed on that day, it was really shocking. Risking your life for freedom. And there were many people here in Tehran or other parts of the world who took this risk. It made me think about history, to try to actually see history.

Eiferman: So this is how the project was born.

Akhlaghi: Yes. I started doing the research and I tried to focus on the people who died in a tragic way, but as there were no cameras around to capture the moment; their death had gone somehow unnoticed.

Eiferman: But aren’t some of these deaths historic turning points for Iran and beyond?

Akhlaghi: Yes. Most of the killings represented are not only tragic but crucial turning points in the particular kind of struggle they represent. In other words, you could always say if any of them hadn’t died in that particular moment, our history would have been different.

Eiferman: How far back in history did you go?

Akhlaghi: I decided to cover the deaths of freedom fighters from 1906 after the Constitutional Revolution in Iran until the Islamic revolution of 1979 and also the Iraq and Iran war.

Eiferman: Can you talk about your process, from the research stage to the reenactment?

Akhlaghi: The research took about three years; I had to study many books and newspapers. Basically all the written words, confidential documents, witness accounts, newspaper articles or even radio reports of the time. For some, I tried to contact eyewitnesses and interviewed them. But many of the people that I spoke to couldn’t remember the details. For instance they could remember the incident, but they couldn’t recall what the weather was like that day.

Eiferman: What was most important to you—recreating the event as close to the truth as possible or constructing a strong photograph?

Akhlaghi: Well, initially, I tried hard to be as factual as possible. But the further I studied, the more I realized that historical precision is just impossible. So instead, I focused on capturing the spirit of the moment.

Eiferman: How was this like shooting a movie?

Akhlaghi: After three years of research by myself, I found a producer and then a crew. We had one month for pre-production and 20 days to shoot all 17 pictures, so we had to be very quick, with only one day to shoot each picture. We had a very low budget so we couldn’t hire actors, and we mostly used friends or extras. But like a movie, I had a professional team with a make-up artist, set designer, assistant director, and everything.

Eiferman: You have a lot of experience in filmmaking; why did you choose to do this series as photographs?

Akhlaghi: I worked as an assistant director for a few years, yes. But I thought staged photography would be closer to the idea of art I had in mind. I was heavily influenced by old paintings but the narrative techniques are borrowed from my old engagement with cinema and literature.

Eiferman: Do you think that today we need strong visual elements to understand events—to remember them?

Akhlaghi: Well, I think for us Middle Easterners who have a tragic history, it is necessary for people to remember the past. And for the moments that have no visual documentation, there is a kind of visual void. With this project, I tried to somehow fill that void.

Eiferman: Did the project change your way of understanding Iran’s history?

Akhlaghi: Yes, the fact that we have so many of these repetitive tragic stories, and how long the fight for democracy has been going on for. When I was doing the research, I had to be selective. It was very hard to pick only 17 of so many freedom fighters who died in similar circumstances. I mean, we had so many journalists, writers, poets, intellectuals who were killed in their homes or in prison, and it’s a story that never ends.

Eiferman: What happened when you showed this work in Tehran?

Akhlaghi: You know, it was seen as revealing a very old secret. Many of the characters of my images are alive in Iran’s collective memory, but we haven’t had a chance to mourn them collectively. The gallery was like a sort of imaginary graveyard, in which each picture was a tombstone for a person whose death went unappreciated by all the regimes of Iran during the past century. It was prohibited to talk or publish a book about many of these figures. So there was a kind of silence surrounding their deaths for many years.

Eiferman: Azadeh, thank you so much for your time. Is there something else you would like to add?

Akhlaghi: Not really, thank you. It is good to be heard by the world.

Originally published on Roads & Kingdoms on May 1, 2014.