In early 1961, the Central Intelligence Agency launched what would become the biggest CIA paramilitary operation at that time in U.S. history in one of the most unlikely places: Laos, a country that today is home to about 6.75 million people. The plan, called Operation Momentum, was initially implemented by Bill Lair, a veteran CIA operative in Southeast Asia. The operation, which Lair began with some of his former Thai paratroopers, would put tiny and obscure Laos at the center of the CIA’s Southeast Asia strategy—and would make it, for a time, a principal focus of America’s foreign policy.

Operation Momentum was, essentially, a plan to arm and train mostly ethnic Hmong fighters, under Hmong leader Vang Pao, to defend their villages, adapt to modern society, and do battle in the growing civil war in Laos. The civil war then raging in Laos, which had gained independence from France in 1954 but remained a weak and divided state, pitted communist insurgents against Laos’ government and its noncommunist allies like Vang Pao. The conflict, which had been percolating for nearly a decade by the early 1960s, had flared up intensely, but the fighting had not yet spread to Thailand or Burma.

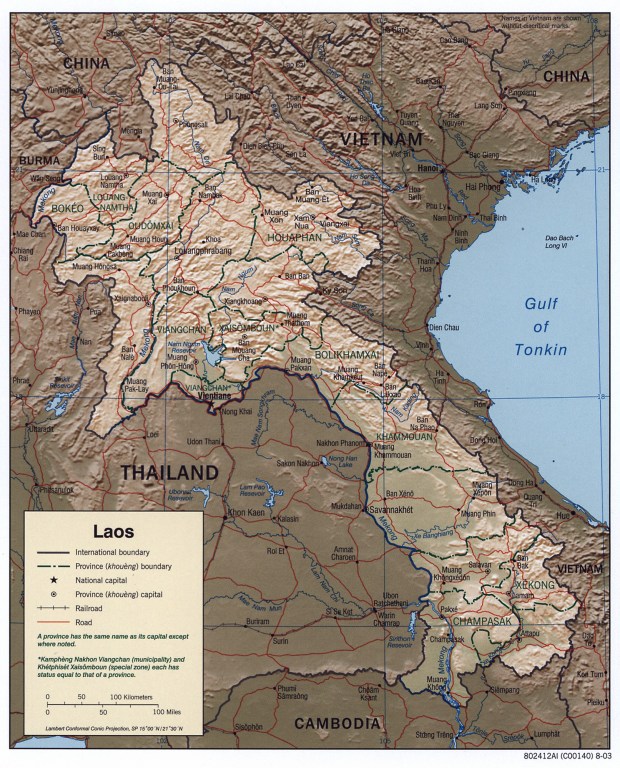

Nevertheless, Washington politicians saw Laos as the victim of a broader effort by international communist forces to dominate Asia—and the world. It seemed not to matter to American leaders that Laos was so small that the capital, Vientiane, was essentially a large village—or that most people in the country lived on subsistence farming and had little idea of different political systems.

President Dwight Eisenhower and his staff, convinced by the domino theory of one country after the next falling to communism, saw Laos as a bulwark, a nation where the United States could make a stand to prevent the ideology from spreading west. The day before John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, Eisenhower organized a foreign policy briefing for the president-elect. Laos came first—before even the looming U.S.-Soviet standoff in Berlin.

The war, which expanded exponentially through the 1960s, would prove devastating in Laos, while ultimately failing to turn the tide of battle in Southeast Asia. Although the CIA leadership had originally signed off on a modest training program for some 1,000 Hmong men, working with Thai allies, the war would grow massively. Initially budgeted at around $5 million, by the end of the decade it would grow into an operation that actually cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Ultimately, the bloated effort in Laos included major U.S. pushes to stop the flow of men and materiel along the Ho Chi Minh Trail into South Vietnam, the fighting by the U.S.-backed Hmong, battles by the royal ethnic Lao army against communists, and multiple other interlocking campaigns.

To support the war, the United States undertook a massive bombing campaign, one that grew over the course of the 1960s and would decimate parts of the country. Washington dropped the equivalent of one planeload of bombs every eight minutes, 24 hours a day—one ton for every man, woman, and child in Laos at the time.

By the end of the 1960s, the Nixon administration was pushing to exit the whole Indochina War, and trying to scale down the U.S. role in Laos and Cambodia—but even so, their activities in Laos continued to expand. Hoping to bleed communist forces from North Vietnam, U.S. leaders prodded Vang Pao and his men to change their approach to fighting.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Vang Pao and his men would shift from guerrilla warfare, the Hmong specialty, to massive conventional battles, with the encouragement of Washington. This proved a recipe for disaster, as the Hmong and their fellow anticommunists were unable to match the North Vietnamese forces in many open field battles. By the early 1970s, Vang Pao’s army was recruiting preteen boys and old men. As his forces were destroyed in larger and more conventional battles, communist forces gained greater control of Laos and other parts of Indochina.

In 1973, the United States signed a peace deal with Hanoi, the primary backer of the Laotian communists; Laos’ anti-communist forces finally fell in 1975. After the mid-1970s, this country, once at the center of U.S. foreign policy, would be ignored by the United States and most of the rest of the world. Yet the legacy of the U.S. war in Laos lives on.

More than 200,000 Laotians—about one-tenth of the country’s total population— died in the war. Nearly twice as many were wounded; almost a million were made refugees in their own country. And Laos became the most heavily bombed country, per capita, in history.

Many of these bombs failed to explode on impact, and they remain lodged in the earth, littered throughout the country, to this day. The painstaking work of cleaning up this ordnance continues; to date, only 1 percent of contaminated land has been cleared. Since the end of the war, 20,000 Laotians have been killed or maimed by these bombs.

In a typical incident in March 2017, in the northern province of Xieng Khouang, a young girl on her way to school picked up a bomb, mistaking it for a toy. When she brought it home, it exploded, killing one child and injuring five adults and seven other children.

In response to steady pressure from non-governmental organizations like Legacies of War and their allies in Congress, U.S. funding for this work has increased significantly—from $5 million in 2010 to $19.5 million in 2016. These resources are used to support clearance efforts that destroy up to 100,000 pieces of lethal ordnance in Laos annually, employing 3,000 workers in the commercial and humanitarian sectors. Casualties from bomb-related accidents in Laos have now fallen to about 50 a year. But to reach zero casualties every year, according to Legacies of War, no less than $30 million a year over 10 years will be required.

Aside from the land that needs to be cleared, there are the more than 12,000 survivors, like those kids in Xieng Khouang, who will need medical, rehabilitative, and psychosocial services for the rest of their lives. The bombs are also a serious impediment to economic development and food security in Laos. For example, according to a joint UNDP-Laos report, at least 200,000 additional hectares of land could be made available for rice production if cleared.

In September 2016, Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. president in history to visit Laos. During the visit, the culmination of years of careful cultivation of bilateral ties, Obama stopped by a rehabilitation center for victims and announced an increase in funds to clean up the bombs. During a speech in Vientiane, he recounted the history of the war and its toll on Laos. “I stand with you,” he said, “in acknowledging the suffering and sacrifices on all sides of that conflict.”

Joshua Kurlantzick is senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. He is the author, most recently, of A Great Place to Have a War: The Secret War in Laos and the Birth of a Military CIA. Brett Dakin, the author of Another Quiet American: Stories of Life in Laos, has served as chair of Legacies of War, a nonprofit organization dedicated to raising awareness about the Vietnam War-era bombing of Laos, and a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations.