Your reading list:

- The Last Forest by G.D. McNeill

Before West Virginia became known as a land where coal reigns supreme, the timber industry arrived with little regard for conservation, wiping hillsides clean of vast, lush woodlands and devastating native trout habitats. The Last Forest is a collection of short stories documenting how a mountain community’s culture was drastically altered when timber companies devastated forests and streams. The book was first published in the 1940s and was out of print for decades until a copy was found at a yard sale and reprinted in 1989.

- Pinnick Kinnick Hill by G.W. González

While Italian immigrants to West Virginia have left a visible legacy with spaghetti houses and pepperoni roll bakeries, the wave of Spanish migration to the Mountain State in the early 20th century remains largely forgotten. G.W. “Bill” González was a first-generation West Virginian whose parents arrived in West Virginia from the Asturias region of Spain in search of factory employment instead of work in the mines. Pinnick Kinnick Hill, named for one of Clarksburg’s once predominantly Spanish neighborhoods, provides a glimpse inside the formerly vibrant Asturian-Appalachian community. The book was published after González died in 1988 and his family discovered the text, which is described in the foreword as “partly a memoir, partly a history, and partly a novel.”

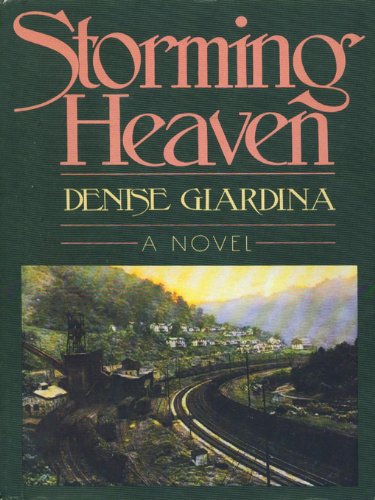

- Storming Heaven and The Unquiet Earth by Denise Giardina

To fully comprehend coal’s impact on the land and people of West Virginia, one must understand the complicated layers beneath the oft-touted promise of economic prosperity. Denise Giardina’s novel Storming Heaven delves deep into the roots of coal’s ever-evolving legacy. Recounting the tumultuous early chapters of Appalachia’s industrial history, Storming Heaven is sometimes a story of greed and oppression and sometimes a story of survival, resilience, and solidarity. The book highlights early labor struggles, including the Battle of Blair Mountain, a violent conflict between thousands of organized miners and law enforcement officers as well as armed mercenaries. In a sequel, The Unquiet Earth, Giardina continues to explore the compelling story of the coalfields decades after Blair Mountain through Cold War politics, federal aid programs, and the notorious Buffalo Creek flood of 1972.

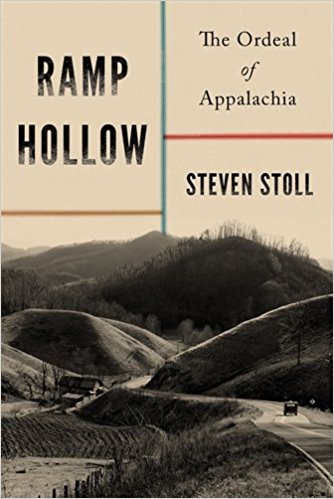

- Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia by Steven Stoll

Fordham history professor Steven Stoll offers a meticulously researched and deeply considered history that cuts to the central issue of Appalachia’s exploitation: land. Rewinding the tape to the region’s first settlers, Ramp Hollow shines light on the dirty lineage of absentee land grabs, dispossession, and backwoods propagandizing that launched Appalachia’s troubled legacy. In the process, he dispels myths that have long plagued Appalachia—from the region’s supposed social isolation to its presumed absence of minorities—portraying its people with a sensitivity and insight that is often lacking.

- Victuals: An Appalachian Journey, with Recipes by Ronni Lundy

Ronni Lundy has been writing about Appalachian food culture for decades. Victuals is a tender and clear-eyed journey around a place that has nourished itself for generations through bounties and hardships. A Kentucky native, she celebrates the former but isn’t afraid to confront the latter, combining casually sophisticated recipes with candid reportage about mountaintop removal mining and the crises facing small farmers. She traverses the region from North Carolina to West Virginia—the only state fully in Appalachia—recording stories that often go untold.

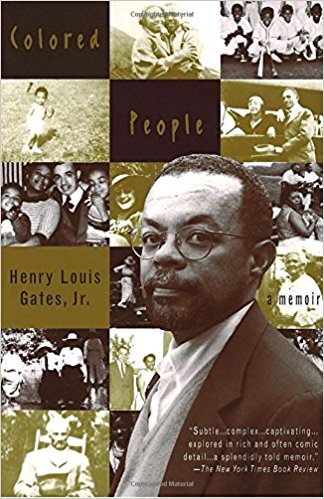

- Colored People: A Memoir by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Henry Louis Gates Jr., is a professor at Harvard University. He is also a native of Piedmont, West Virginia. In his 1994 memoir Gates—a public intellectual, filmmaker, writer, and historian—revisits his 1950s and ’60s mill town childhood, with vivid stories of his family, religion, racism, and the integration of his school after the Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision.

- Electric Dirt: A Celebration of Queer Voices and Identities From Appalachia and the South by Queer Appalachia

Bluefield native Gina Mamone is a founder of Queer Appalachia, a collective of LGBTQ writers, artists, and musicians from across the region. What she thought would be a one-off zine ballooned into a 200-page publication with personal essays, fiction, poetry, and visual art. In West Virginia, the state with the highest percentage of teens who identify as transgender, Queer Appalachia is a celebration of a community often marginalized by the predominant narrative.

Know before you go:

- Learn a little history. The early 20th century was a tumultuous period in the rights of miners, who worked in brutal conditions under nearly feudal oversight. The West Virginia Mine Wars Museum is in a building that still bears bullet holes from the Matewan Massacre, a 1920 shootout with pro-union miners and local law enforcement versus union-busting private detectives hired by the Stone Mountain Coal Co. A year later, the fight for workers’ rights erupted in the dramatic but largely forgotten Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest armed insurrection in U.S. history outside of the Civil War.

- Drink more than just moonshine. Yes, moonshine is a piece of Appalachian drinking culture. No, it’s not the only one. A slew of craftspeople carry on traditional methods and explore new ones in West Virginia breweries and distilleries. Sample cider from Hawk Knob, which blends Old World winemaking knowledge with traditional Appalachian ciders. Have a Devil Anse IPA (named for the Hatfield patriarch) in the taproom of Greenbrier Valley Brewing. Sip wheated bourbon from Smooth Ambler, a distillery that revives the state’s whiskey history with handcrafted spirits and independently bottled finds from around the world. Stop by family-run Short Story Brewing in Rivesville for a pint of Hunt and Peck brown ale or grab a growler of Halleck pale ale from Morgantown’s Chestnut Brew Works. In the Allegheny Mountains in Randolph County, the West Virginia natives who run Still Hollow Spirits are making corn whiskey from a 200-year-old strain of Bloody Butcher corn; stop by the tasting room for a sample.

- The hills are alive with the sound of … You guessed it. West Virginia is famous for its music festivals. In early August, musicians from around the world descend on Camp Washington-Carver in Fayette County for the Appalachian String Band Festival, more commonly known as Clifftop. The setting, in a forested campground on the rim of Glade Creek Canyon, begs for the drone of fiddles and the rhythmic thump of banjo strings. But West Virginia’s music scene is more than old-time and bluegrass. In March the Black Sacred Music Festival now held in Huntington, returned to celebrate the rich gospel traditions of West Virginia’s vibrant African-American communities. The festival’s founder, Ethel Caffie-Austin, is a Mount Hope native and world-renowned gospel musician featured in the documentary His Eye Is on the Sparrow. There’s also the Travelin’ Appalachians Revue, a mobile festival highlighting the work of young creatives—musicians, writers, poets, visual artists—that tours the state each year around West Virginia Day (June 20, the anniversary of the state’s admission to the Union).

- Experience the wild side of “Wild and Wonderful.” Though it has suffered widespread environmental devastation, West Virginia has some of the biggest tracts of federally protected public land in the eastern U.S. The New River Gorge National River boasts world-class rock climbing and whitewater rafting. At almost 1 million acres, the Monongahela National Forest contains hundreds of miles of hiking and mountain-biking trails. With their scenic beauty and endless outdoor recreation opportunities, West Virginia’s public lands have provided a much-needed boost to the state’s economic diversification efforts, creating thriving gateway communities such as Fayetteville, Thomas, and Lewisburg.

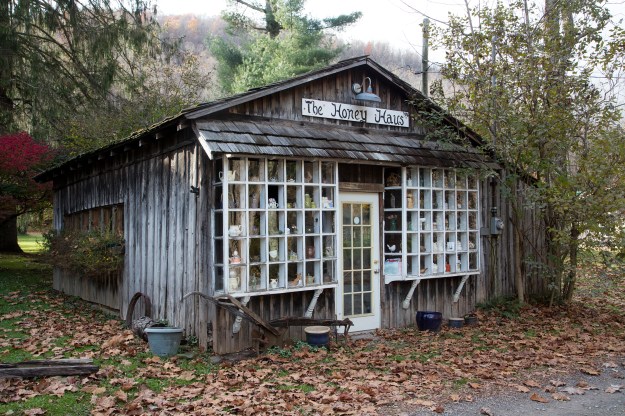

- Visit West Virginia’s Swiss community. The village of Helvetia was founded in 1869 by a group of Swiss families seeking fertile land and a place to practice their art and trades. The remote community, with a population of 59, has retained a lot of Swiss culture. Check out the hand-painted signs inspired by Swiss canton coats of arms or eat some traditional bratwurst and sauerkraut at Hütte, the town’s only restaurant. Helvetia has an annual celebration called Fasnacht, a kind of mountain Mardi Gras to celebrate Swiss customs and lure tourists during the winter months.

- There are so many festivals. Residents often boast that West Virginia has the most festivals per capita in the country. Even if that’s not true, these community celebrations are some of the best ways to encounter local culture—the music, dancing, and most important, food made by home cooks from diverse communities. The Lebanese community in Wheeling hosts the Mahrajan Festival. Expect kibbe, stuffed grape leaves, lamb shish kebabs, and traditional Lebanese music. Up the road in Weirton, the annual Serbian Picnic is held in July. The local Serbian church’s men’s club roasts hundreds of chickens and dozens of lambs on spits and offers pierogi, cabbage rolls, and sljivovica (plum brandy) while a Serbian band plays.