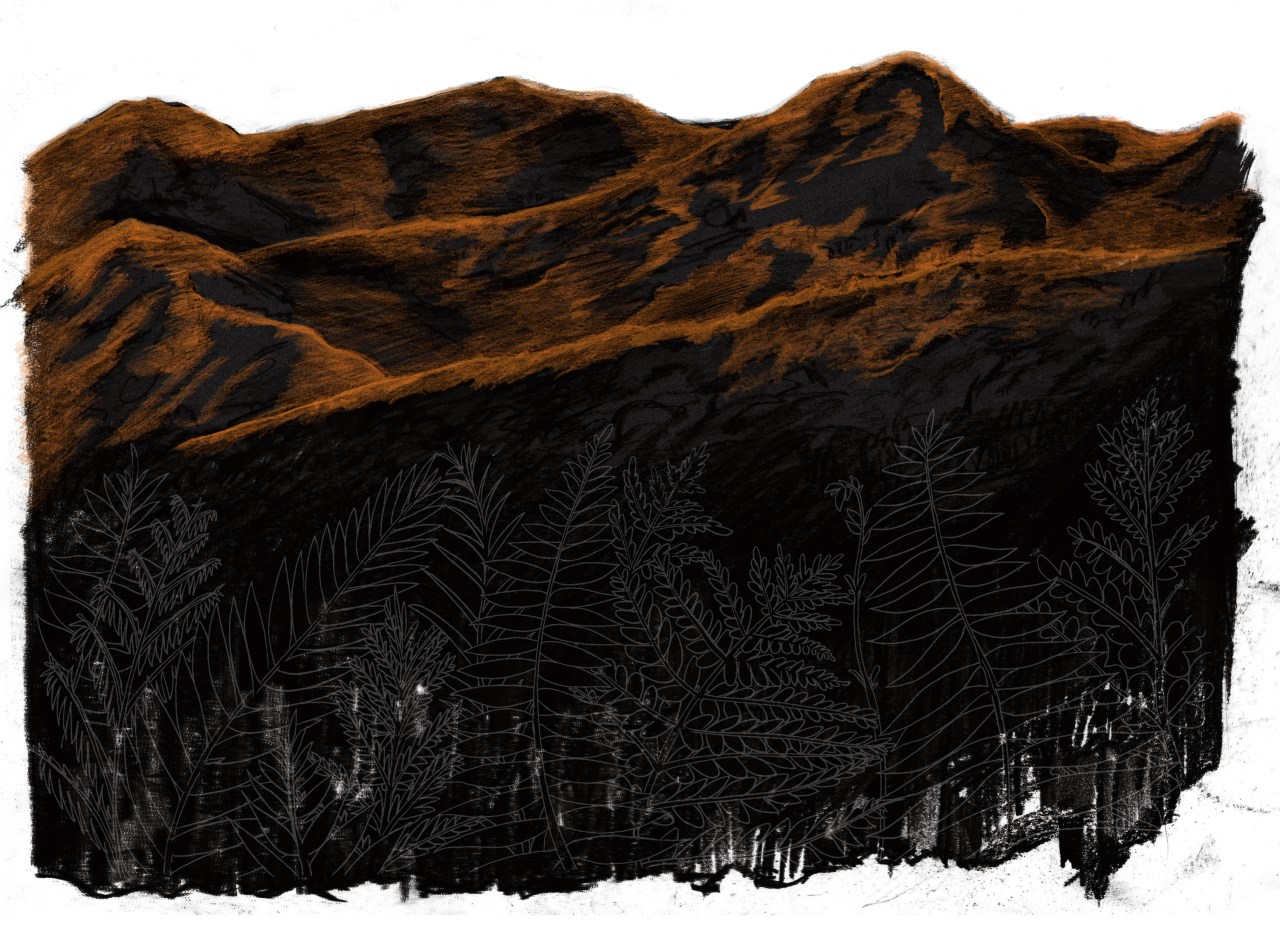

The roofs of coal mines are often lined with the fossils of ancient forests, the outlines of plants and trees buried for millions of years. Miners today can see the same stone patterns that their fathers and grandfathers saw decades ago as they dug into the mountains of West Virginia.

Many Appalachian families trace their roots to migrants who fled tenant-farming abuse in Ireland or indentured servitude on plantations in the New World. Those migrants found freedom in the mountain wilderness. But that freedom came under threat when the commercialization of coal kicked off in the late 1800s. What was thought to be a blessing has often been a curse, opening the doors to land grabs, corruption, and enduring poverty. The people of Appalachia came to be dominated by the wealth of natural resources beneath their land—and outside forces seeking to exploit it.

Discovery and deceit

In the early 19th century, Appalachia was rich with old-growth hardwood forests and coal. In the years following the Civil War, wealthy capitalists began scouting the mountains for resources to fuel industries like steel, railroads, and electric power.

Speculators and investors exploited poorly documented deeds and surveys, and many unassuming landowners sold their timber and mineral rights for a pittance or under coercion. By 1920, 70 to 90 percent of Appalachia’s mineral rights were owned by corporate interests, which also owned more than half the privately held land.

Coal camps

With land rights firmly in hand, railroads like Chesapeake and Ohio and Norfolk and Western built access to remote regions of the mountains to extract the wealth. Timber companies clear-cut old-growth hardwood forests, eliminating a major means of self-sufficiency for Appalachian families. And coal mines began to open. To meet the insatiable need for workers, coal companies built coal camps and towns to house migrants recruited from Northern cities and African-Americans who had left sharecropping plantations. The majority of these coal communities became places of misery. Upon arrival, workers found they were indebted to the company for their family members’ train rides to the mountains and their first month’s rent in a company house. Workers were required to open a line of credit at the company store to buy their first rations of food, clothing, and the equipment necessary to mine coal. Many companies, including the Consolidation Coal Co. (today known as Consol Energy), paid employees only in company scrip, a form of currency usable only at company-owned establishments and for company-provided services.

Rise of labor movement and company violence

Mining was extremely dangerous. Without government regulation or labor rights, miners worked 16-hour days. An estimated 95,000 miners died in the nation’s coal mines from 1900 to 1950, according to Mine Safety and Health Administration records. Tens of thousands more succumbed to black lung disease or were permanently disabled in mine accidents.

As exploitation worsened, miners fought back and organized. In 1890 a merger between two labor organizations created the United Mine Workers union in Columbus, Ohio. As the union grew nationwide, it was able to help miners in the Appalachian fields face off against powerful companies and demand living wages, health care, and improved mine safety.

Company owners employed various tactics to stop organizing efforts, from segregating coal camps by race and ethnicity to outright violence. Hiring mercenaries known as mine guards was commonplace in the early coal camps. These men were known to brutally enforce anti-union company policies, often with the support of local politicians and law enforcement.

Battle of Blair Mountain

A series of clashes culminated in the Battle of Blair Mountain in August and September of 1921. More than 10,000 armed union miners from the northern coalfields of West Virginia marched south to support unionizing efforts amid an anti-union regime in Logan County. The miners were met with the West Virginia state police and machine gun nests manned by mine guards. The governor sent in the National Guard, and over 900 miners were indicted on various charges. Though the number was never confirmed, it is believed that anywhere

from 20 to more than 100 men were killed in the standoff.

Rise of the machines

While the persevering miners and their families won many battles for union contracts that provided better wages, health care, pensions and safety, those gains were short lived. As machines replaced workers in the 1950s, coal mining employment dropped by the tens of thousands, paving the way for poverty in the mountains.

Throughout industrialization, self-sufficiency had become increasingly difficult for Appalachian residents. Increased populations from coal camp recruitment, clear-cut forests, absentee land ownership, and the need to divide land among heirs played roles in forcing Appalachians from their lives of agrarian freedom to one of economic dependency on a single industry.

Throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, many Appalachian families left their beloved mountain homes to find work in Northern cities.

War on Poverty

Before his 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy visited West Virginia and brought attention to the region’s poverty. His successor in the White House, Lyndon Johnson, launched the famous War on Poverty. Networks flooded the airwaves with news and TV specials that exploited the region’s poverty for ratings. Few people watching took into consideration the underlying causes. Americans instead reflected on caricatures of Appalachians as backward, inbred hillbillies. Mountaineers once again found themselves dehumanized as a consequence of the natural resources beneath them.

Mine safety and the energy crisis

The 1970s brought with it the oil crisis and increased demand for coal. New mines were opened, and the strength of the United Mine Workers increased as well. National news broadcasts brought mining disasters into people’s homes. In 1968, Americans saw footage of the aftermath of the Farmington mine disaster, which killed 78 miners. The new publicity surrounding mine disasters aided the United Mine Workers, which seized the opportunity to push safety legislation, with the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 and the Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977.

For 15 years, miners enjoyed safer work conditions with better pay and benefits than ever before. But by the 1990s, coal prices had fallen, and once again thousands of miners were unemployed. The number of union operations fell dramatically throughout the 1990s and few mines were represented by union contract in the 2000s.

Throughout the 2000s, international demand for coal increased, as did market prices. Companies responded by opening new mines, many of which were non-union, offering slightly higher wages than union contracts along with prices that mines were safer than ever before.

Mountaintop removal

Not only had coal companies decreased their labor overhead through union busting in the 1990s, but they also continued to mechanize the industry. The most glaring example was the increased use of mountaintop removal mining. Surface mining laws allowed companies to use explosives and massive machinery to take off the entire tops of mountains to access coal seams. The rubble from the mountaintop was then dumped into adjacent valleys.

A few affected community members and landowners worked diligently to raise awareness about the issue. When local activists began searching outside the region for help, an influx of environmental activists from all over the nation went to Appalachia to protect the mountains. Though well meant, their tactics and messaging grated against the local culture, leaving mining families feeling demonized for their sacrifices.

Coal industry associations and lobbying groups quickly countered the negative publicity by rallying mining families against a “war on coal.” Coal company associations adapted their marketing to the culture of mountain people and sponsored local and collegiate sporting events, racing teams, and Boy Scout Jamborees.

Appalachia today

Today corporate and absentee land ownership continues to affect the balance of political and economic power in the region. Little if any land or mineral rights have found their way back to people living there. With the majority of resource rights still held by outside interests, economic and political power remains in the hands of extractive industries looking to make a profit. This has crippled the possibility for an equitable transition away from coal. Big businesses enjoy low taxes, while the communities from which they draw their vast wealth are dealing with constant budget shortfalls in public education and basic infrastructure.

Data from the Appalachian Regional Commission show that year after year, Appalachia’s coal-producing counties find themselves in the most economically distressed 25 percent of the nation’s counties. Some are in the top 10 percent.

Many people who can move away do; those who can’t leave face growing problems, including an opioid epidemic that some say was largely driven by the pharmaceutical industry.

The people of Appalachia have endured much over the past 150 years. They’ve lost nearly everything in the face of the country’s insatiable desire for the energy and steel that coal has helped produce. Despite the sacrifices they’ve made, Appalachians continue to bear the burden of hillbilly stereotypes and national ridicule. As America’s energy portfolio continues to evolve and as the once abundant reserves of Appalachian coal dwindle, it seems the people of Appalachia will have to endure even more.