A few days before the West Virginia teachers’ strike began, Meghan Stevens, an English teacher at Poca High School, tied a red bandanna to her backpack. When her students asked her what it meant, she told them it was a symbol borrowed from Appalachian coal miners nearly a hundred years ago. Miners who supported unionizing wore bandanas around their necks, inadvertently giving rise to the term redneck.

And as a teachers’ strike seemed more and more likely in February 2018, she explained to her students that she was resolved to do her part. “I told them all along that if it came down to it, I loved them dearly, but I saw the greater good, the greater cause,” she said.

In addition to stagnant wages and rising health care costs, she was worried about future generations of West Virginians and her profession as a whole. She wanted to make sure that her six-year-old daughter would have qualified teachers in her classroom, since she saw young teachers leave the state in droves for better wages and benefits elsewhere.

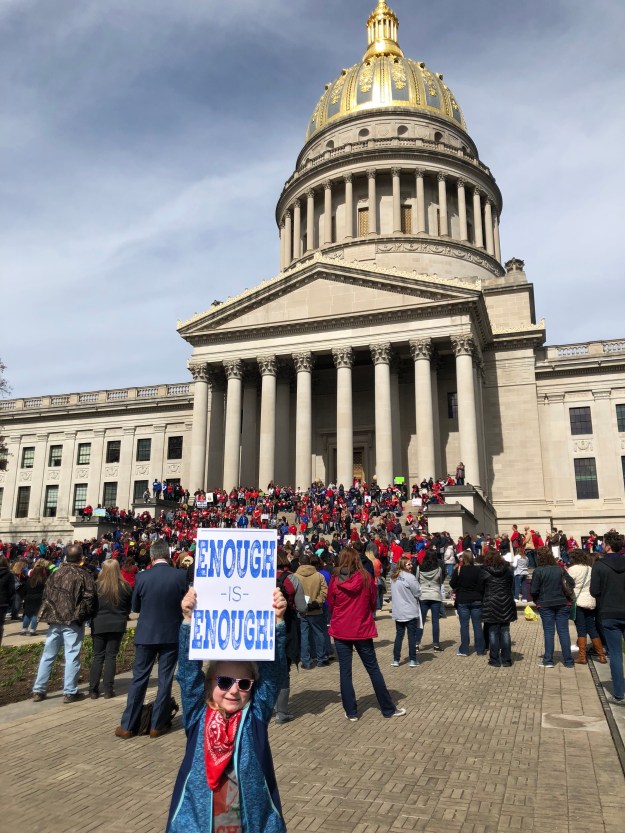

On Feb. 22, Stevens was one of thousands of teachers standing outside West Virginia’s gold-domed Capitol, shouting about solidarity and economic justice.

Wearing a red bandanna around her neck, she hoisted a Star Wars-themed sign that read, “Teachers strike back: We will resist the dark side!” and, quoting Yoda, “Do or do not, there is no try.” Earlier she worried that a winter storm would kill the momentum, but when she saw the crowd on the Capitol steps, she knew that this was the beginning of something remarkable.

On that day, nearly 20,000 teachers and 13,000 other school personnel in West Virginia went on strike in response to low wages and rising health care costs. In doing so, they closed down all public schools in the state and began the first strike in the state’s history to involve all three school workers’ unions and all 55 counties. It was an unexpected show of Democratic labor values from a state that has voted overwhelmingly red in recent years. West Virginia teachers’ average pay ranked 48th in the nation, according to the National Education Association, and they had finally had enough.

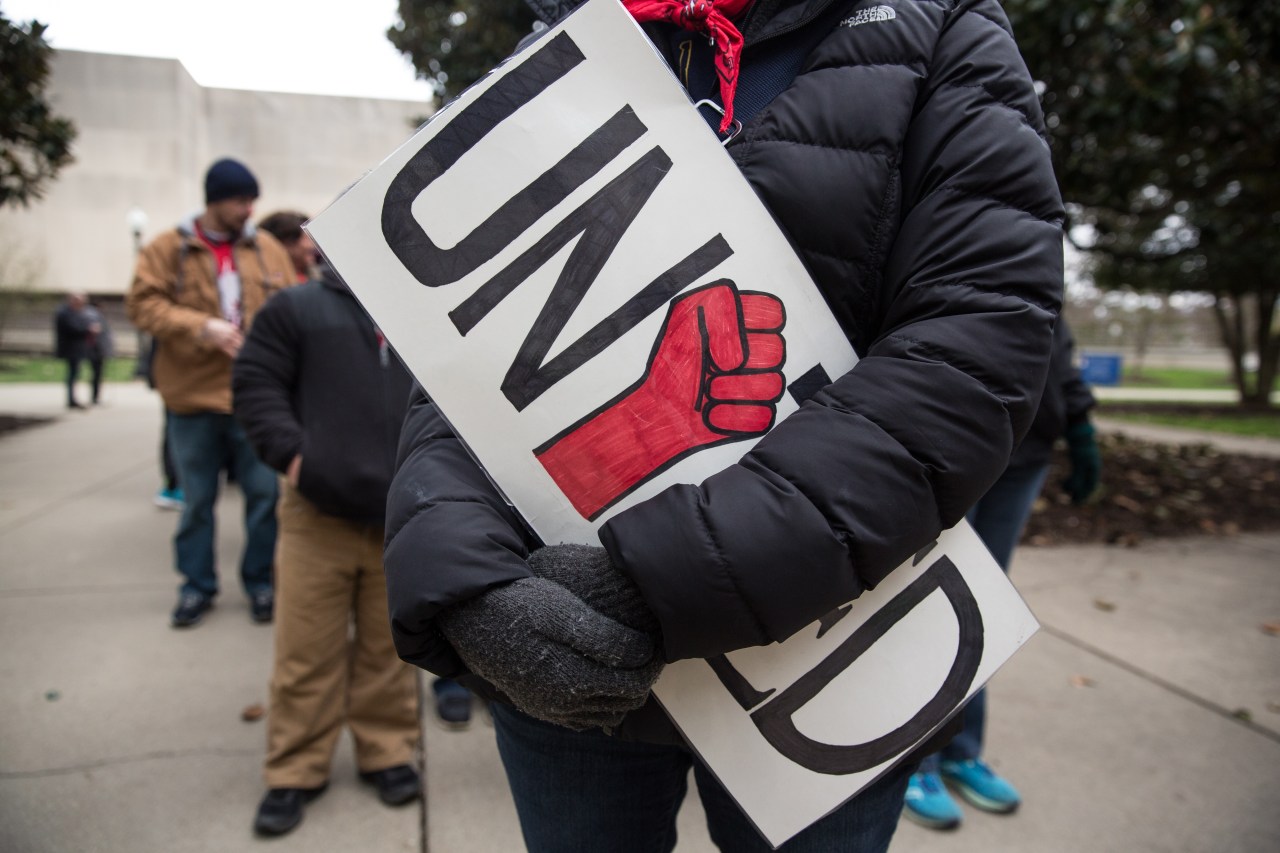

Bundled in parkas and ponchos and brandishing umbrellas and elaborate signs, the teachers who gathered in front of the Capitol—many of them women—were channeling the anger and willpower that fueled Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, Sarah “Ma” Blizzard, and countless other United Mine Workers of America organizers who came before them. Many strikers wore red T-shirts and red bandanas as a symbol of defiance and solidarity, placing themselves in the tradition of mining families a century earlier.

Fourth-grade teacher April McConihay tied on her bandanna and headed to the Capitol after setting up a food bank to make sure her students would be fed while school was shut down.

“It’s a symbol of the unity of all the teachers right now,” she said, “but it was drawn from the Mine Wars and the miners who wore red bandanas to identify themselves as strikers. We’ve adopted that symbol because we feel that our fight is very similar. We will not continue to let our kids be oppressed in this system. The entire system needs to be changed.”

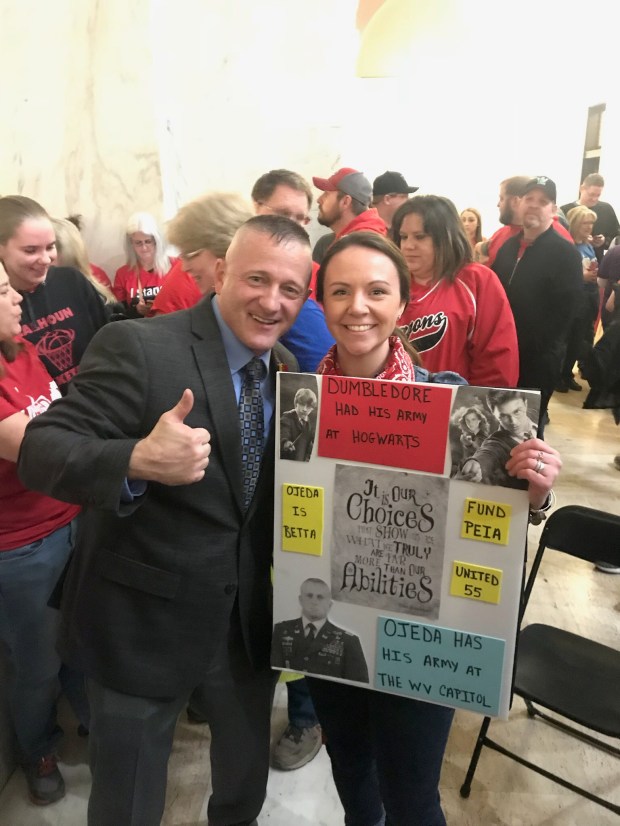

On the steps of the Capitol, speakers gathered under a tent bearing the seal of the United Mine Workers of America, many of whose members came out to support them. Teachers took to the microphone and told stories of working multiple jobs to be able to support their families.

Sailing down the nearby Kanawha River, a tugboat hauling coal barges sounded its horn in solidarity.

In August and September of 1921, the hills and hollers of southern West Virginia echoed with machine guns and bombs as 10,000 unionist coal miners faced off with coal industry forces in the largest armed insurrection in the U.S. since the Civil War: the Battle of Blair Mountain.

It was the climax of West Virginia Mine Wars—two decades of political activism, violence, and conflict between working families and wealthy coal industrialists. In an effort to prevent unionization, coal companies trampled on the miners’ First Amendment rights and imposed authoritarian rule in the company towns where most working families lived. Armed mine guards acted as a private police force for the coal companies, violently evicting union sympathizers from company housing with little notice, threatening organizers’ lives and livelihoods and limiting their freedoms of speech and assembly.

The spark that finally set Blair Mountain ablaze in gun fire in the summer of 1921 came when Governor Ephraim Morgan rejected a list of the unionist miners’ demands for reform, just days after Sid Hatfield, one of their most beloved leaders, was assassinated by a coal company spy in broad daylight on the McDowell County steps. A call went out for pro-union miners to gather on the banks of the Kanawha River. Miners—some of whom had fought in World War I—came from neighboring counties as well—descendants of former slaves, immigrants who fled servitude and famine in Europe, and mountaineers whose families had lived on the land for generations.

After several days of mustering, they struck out for Mingo County, where some of their union brothers were imprisoned under martial law. Their goal was to liberate the men and unionize the territory in between. Fifty miles into their march, they clashed with coal company forces along a remote ridge on the border with nonunion Logan County: Blair Mountain.

The Logan County sheriff assembled several thousand mine guards, state police, and middle-class citizens to fight the rednecks. He even hired planes to drop bombs on them. The battle lasted four days, and dozens lost their lives in guerrilla-style warfare.

The two sides surrendered peacefully when U.S. troops were sent in. Curiously, they both saw the federal government as their liberator. Afterward, hundreds of miners were indicted for treason and murder.

The decades after the Battle of Blair Mountain were a period of forgetting more than remembering. During the trials that followed, the press and middle class shamed participants, and discussing it became taboo. West Virginia history textbooks didn’t include Blair Mountain until the 1970s.

Some teachers keep this history alive in their classrooms, presenting it alongside lessons on civil rights struggles and slavery. A handful teach the crucial but mostly overlooked role of women in during the Mine Wars. Activist Mary Harris “Mother” Jones galvanized the miners with her fiery rhetoric along their pathway to unionization; in 1913, fellow activist Sarah “Ma” Blizzard led a group of unionist women to tear up the railroad tracks after a gang of mine guards, operators, and local law enforcement officers rode an armored train through a strike camp and shot it up with machine guns and rifles.

And others are just discovering the ways in which the Mine Wars reflect their own experiences.

“If they hadn’t already walked this path, it would not be as easy for us,” said April McConihay, who was part of a crowd that surrounded Gov. Jim Justice’s car and forced him to stop and answer questions about a settlement deal that he proposed. “They paved the way for us, the miners did.”

Like mining families in 1921, the teachers of 2018 worked across their differences. Democrats and Republicans, buttoned-up principals and camo-clad janitors all stood side by side to present a unified voice.

And the miners and the teachers defied their own leaders to push forward with their demands. Five days into the teachers’ strike, union heads met with Justice and declared victory with a proposed 5 percent raise for school employees. But the rank and file rejected the deal, still concerned about health care and doubtful that state Senate Republicans would pass the raise, and resorted to a wildcat strike. Likewise, the miners at Blair Mountain moved forward without the support of their district leaders, who had told them to turn around and go home. The teachers and the marching miners were willing to break step with their unions if necessary and assert their independence.

“The teachers who have rallied at the Capitol over the past week—many of them sporting red bandanas, just like the miners at Blair—recognize this proud history,” said Jack Seitz, the lead educator at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, who directed teach-ins at the Capitol during the strike. “Legislators who do not recognize this do so at their own peril.”

Victory for the Blair Mountain miners wasn’t linear or clear cut. In fact, for a decade, it seemed they failed: Union membership in the state plummeted. But in 1933, Congress passed legislation guaranteeing the right to unionize, ushering in an era of relative prosperity for the miners that lasted into the 1980s.

Because of increased mechanization, union-busting efforts by coal corporations in the 1980s, and a resulting decrease in membership incentives, the many working miners in central Appalachia are now non-union. Those who remain organized are mostly retired, consumed with a fight to retain health care and pensions from bankrupt coal companies.

But this year, teachers in West Virginia demonstrated that labor can still be a powerful voice and vehicle for working people, even in a right-to-work state.

On March 6, West Virginia teachers won a 5 percent raise for public school teachers and other school personnel and all state workers, as well as a task force mandated to address their health care concerns. On the day of their victory, they linked arms and sang “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” the state’s unofficial anthem.

With each passing week, more states are following West Virginia’s lead. Oklahoma teachers recently won a salary increase after a nine-day walkout just as Colorado’s teachers walked out of their classrooms to demand more pay. In Kentucky thousands of teachers protested their broken pension system, prompting the legislature to override the governor’s veto. And Arizona teachers recently voted to strike. Red bandanas have been spotted at all those teachers’ demonstrations.

Meghan Stevens has been in touch with fellow educators across the country via social media, offering lessons and success stories. “It’s really been inspiring to see it take hold nationwide,” she said. “I’m proud of the fact that West Virginia was first for once, taking a stand and teaching other teachers how to fight.”