Armenians love to party. They find any excuse to revel in the streets with some sizzling barbecued kebabs in hand and plenty of lavash bread to go around.

And often alcohol is the star. Every October, scores of people from around the world flocked to the village of Areni, where, a few years ago archaeologists discovered the earliest known winery in a cave dating back to 4,100 B.C.

Winemakers from all over the country, including local independents working out of their garage, gathered in Armenia’s Vayots Dzor province to offer their finest vintages at the annual Areni Wine Festival.

For millennia wine in Armenia was produced using the same painstaking method and stored in the traditional karas, a ceramic vessel that is still employed to this day. Wine was used for divination in ancient shrines about 3,300 years ago.

Greek historian Herodotus, of Halicarnassus, documented the transportation of wine from Armenia down the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in the 5th century B.C. Armenian winemaking culture has endured the test of time, repeatedly surviving regional wars and conquests. The intensely rich volcanic soil is an enduring symbol of eternity for Armenians, and wine exemplifies longevity.

The main focus of Armenian wine has traditionally been Areni, an ancient ovular-shaped red varietal (which got its name from the region in which it grows). The problem with Areni is that it has been over-propagated to meet the high demand, mostly from Russia. As a result the quality of the grape has diminished, and many Armenian grape varietals that were historically used for winemaking have been lost or are in danger of dying out.

Now the country is undergoing a winemaking renaissance. Armenia’s sacred, time-honored winemaking traditions and legacy have cast their spell on some of the industry’s powerhouse winemakers.

Areni recently found worldwide acclaim thanks to Zorah, producer of a wine called Karasì, which was featured on Bloomberg’s Top Wines of 2012 list. The resurgence of the winemaking industry is part of the Armenian government’s Sustainable Agricultural and Rural Development Policy.

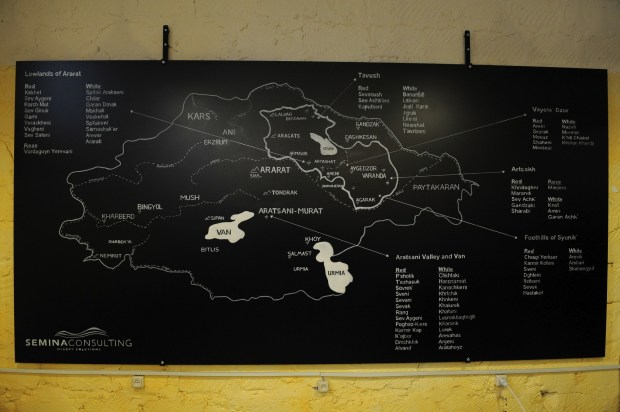

Vahe Keushguerian is leading the charge. Keushguerian runs a winery solutions company called WineWorks (formerly known as Semina Consulting), which is using modern methods to craft new wines from historic varietals indigenous to the region.

His substantial Hin Areni Winery is packed wall to wall with winemaking equipment from Italy. Dozens of steel fermentation tanks are lined up in rows. And there are dozens of French oak barrels, the lofty piles of which resemble a honeycomb pattern.

Plenty of cabernet glasses are on hand, arranged on a couple of stainless-steel service carts. On another cart a few label-free wine bottles are marked with special tags bearing code names. These are the hush-hush experimental wines.

When I first visited the state-of-the-art winery, situated in a Soviet-era storage facility in Ajapnyak, a northwestern district of the country’s capital city, Yerevan, I sampled the Hin Areni, a blend Keushguerian released in early 2015. The premium wine has garnered high praise and features hints of Campari, cranberry, extra-dark chocolate, and moss.

Keushguerian has been in the wine business since the mid-1990s. He made his start in one of the centers of Old World winemaking: Tuscany. Born in Aleppo, Syria, he first went to Armenia as a tourist in 1997. Like many Armenians who were born and raised in the diaspora, he instantly fell in love with the mountainous landscape, ancient stone monasteries, and rustic hospitality.

Then a professor he knew in Tuscany told him that Armenia was believed to be the birthplace of winemaking, a possibility that intrigued him. In 2009, after a 15-year stint producing Chiantis for export in Italy, he set his sights on Armenia.

Shortly after his arrival he found out about a businessman who had just planted 500 hectares of grapes in the Armavir region of the country. The plan was to supply local brandy-production companies, but Keushguerian offered to conduct a winemaking experiment with the grapes: from 1 ton each of chardonnay, syrah, and tannat. The results were so good that the experiment launched Armavir Vineyards, which now produces a popular wine called Karas.

“It’s important that we make wines outside the limits of everything, we push the limits,” says Keushguerian. “Ninety percent of Armenian grapes are used for brandy. Armenia has nearly 17,000 hectares of vineyards, and about 1,500 hectares are for wine.”

Boutique winemaker Varuzhan Mouradian, the founder of Van Ardi winery, is doing similar work. Much of his wine is now being exported to Russia as well as to the south of France. The 2014 Van Ardi was by far one of the best Arenis I have ever tasted. The color is dark and bold, while the bouquet features hints of blueberry and a faint suggestion of fennel.

The wine explodes on the palate with pronounced nuances of Bing cherry, rose hip, grapefruit, and especially bastegh, the smoothed-out tangy delicacy often made from grape juice that inspired Fruit Roll-Ups. “It’s a shame that there is such a focus on Areni,” Mouradian says. “There are so many other Armenian grape varieties that need preserving.”

Keushguerian agrees. His vine nursery is dedicated to bringing these lesser-known varietals back to life. Proper Areni wine is made not only from Areni grapes but also from other varieties, indigenous to Armenia and commonly planted in the region: moghuz, tozot, and seyrak.

Armenia is where some of the oldest known varietals are preserved. The Vitis vinifera is believed to have emerged from this country in the heart of the South Caucasus.

But one of the biggest obstacles to producing Areni wine has been the availability of quality grapes. Since Areni is in such high demand, many grape producers tend to overwater the vineyards and harvest early.

Before propagation can begin at Keushguerian’s nursery, cuttings are sent to Mercier in France for analysis so that plants containing viruses can be weeded out. It’s a huge investment, he says, but he’s starting small. And no one else is doing this imperative work. “I’m passionate about Armenian wine 24/7,” Keushguerian says. “It’s not the wine per se, but it’s developing an industry that interests me, changing the narrative.”

Originally published on Roads & Kingdoms on October 28, 2015.