Once an ancient kingdom that stretched from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean, Armenia became a fragmented nation in the wake of the 1915 genocide—a characterization Turkey continues to deny—that sparked a mass exodus.

So when, following 70 years of Soviet rule, Armenia became a sovereign nation in 1991, the Armenian diaspora rejoiced. Although there was an initial repatriation of some 70,000 to Soviet Armenia in 1945, post-independence repatriation was different. This time the individuals weren’t recovering from the tragedy—they were the descendants of exiles who had created fruitful lives across the globe. They wanted to help their ancestral homeland gain footing after centuries of outside rule.

Many have come of their own accord, seeking self-reinvention and a chance to contribute to Armenia’s development. Others have come seeking refuge: More than 14,000 Syrians of Armenian descent have arrived in recent years, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees.

To be sure, more have left: Around 1 million Armenians have emigrated (PDF) to Russia and the United States, among other countries, since the early 1990s.

But where many see poverty and joblessness, the repatriates see hope and opportunity.

Repatriates are implementing progressive programs in the fields of education and public service with the hope of reviving a badly bruised country. After arriving from the United States, Australia, Syria, and several other nations, they set up businesses and nonprofits. Armen Der Kiureghian, who has a PhD in engineering, returned to his ancestral homeland to run a university, and Roffi Petrossian became a horticulturist who moonlights as a local TV actor. For them, and some of the other Armenians featured here, it’s an opportunity to not only reinvent themselves but also take advantage of the opportunity that escaped their parents and grandparents: pioneer change in Armenia from within.

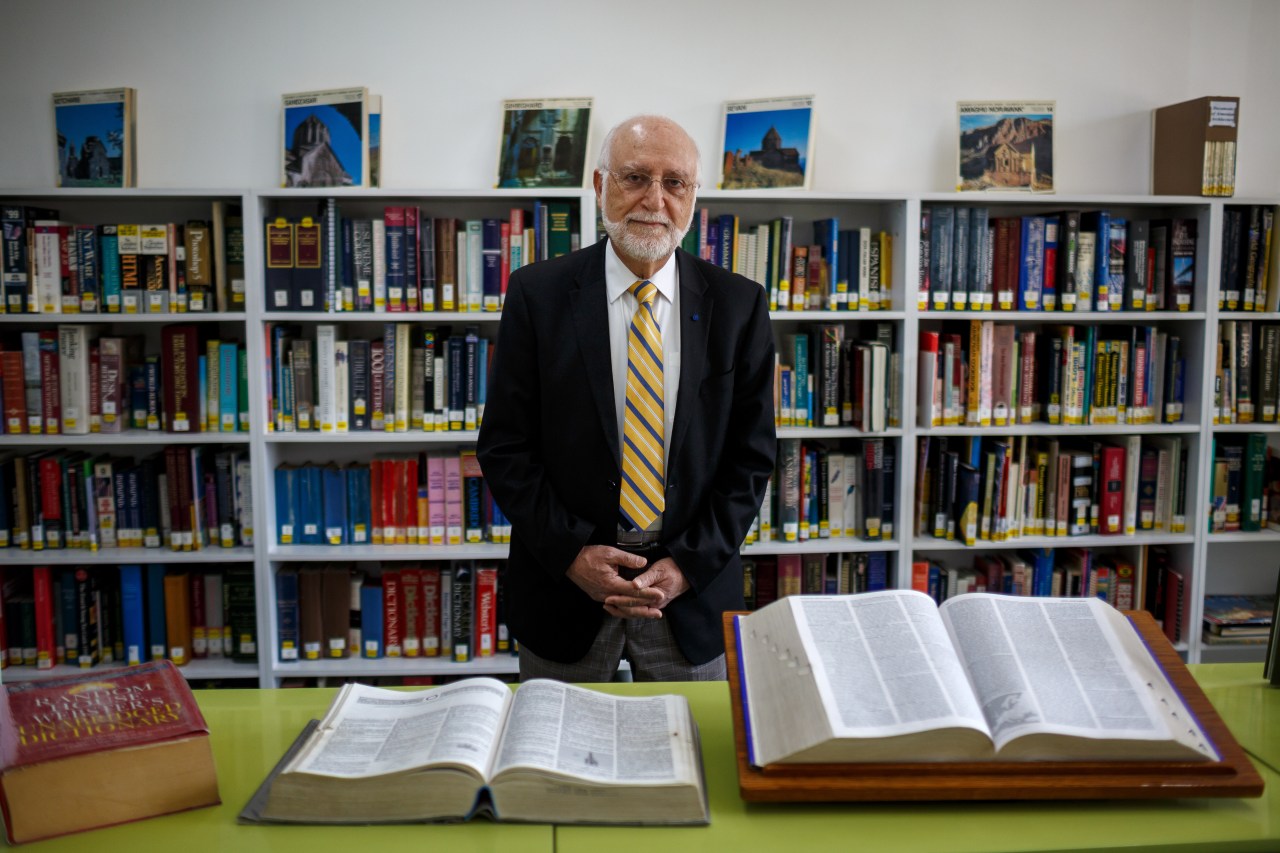

Armen Der Kiureghian, university president

Birthplace: Isfahan, Iran

Years in Armenia: 4

When a devastating earthquake struck Armenia in 1988, Der Kiureghian, 70, joined a team of seismologists and earthquake engineers and traveled to Armenia to assess the damage.

A civil engineer and professor at UC–Berkeley, Der Kiureghian, who was born into an Armenian family in Iran, was struck by the level of destitution in his ancestral homeland. “Because of the blockades [from Turkey and Azerbaijan], there was no power, gas, or heat,” he said.

Just three years later, he helped to establish the American University of Armenia (AUA), the only U.S.-accredited institution in the former Soviet Union. The school opened the day Armenians voted for their independence in September 1991. Der Kiureghian resettled in Yerevan in 2014 when he was appointed the university’s president.

“If this university was not here, I would say half of our students would go abroad,” he says. Despite Armenia’s reputation for producing scientists, inventors, and—yes—chessmasters, he says high unemployment and limited education opportunities have created something of a brain drain.

Der Kiureghian thinks the university can help to reverse that brain drain. And he’s bullish on Armenia, noting a growing tech sector and flourishing wine and tourism industries with excellent food.

But it’s students he’s most optimistic about—he says those who grew up in an independent Armenia are entrepreneurial and open-minded. “They are the ones who will change Armenia fundamentally for the better.”

Gomidas Merjanian, winemaker and sommelier

Birthplace: Aleppo, Syria

Years in Armenia: 6

As a child, Merjanian, 30, remembers his father crushing grapes to make wine in their home in Aleppo. As his passion for wine grew, Merjanian dreamed of learning his father’s art in Armenia, a country known for its thousand-year-old winemaking tradition. In 2012, a year after the civil war began in Syria, he packed his bags and joined thousands of other Armenian-Syrians who sought refuge in their ancestral homeland.

Merjanian enrolled in Yerevan’s EVN Wine Academy, where he studied the business and craft of winemaking. He worked at popular wine bars in downtown Yerevan, eventually becoming an assistant winemaker in Vayots Dzor, a region that traces its wine history back 6,000 years.

“I have loved winemaking all my life,” Merjanian says. “But my love deepened when I arrived in Armenia and learned that the earth’s first vineyard was planted by Noah in historic Armenia, just a few feet from Mount Ararat.”

Merjanian, who hopes to open a boutique vineyard one day, says Armenia has changed tremendously since he arrived. “Locals tell me that the hayrenatartz (repatriates) have brought positivity to Armenia with their hospitality and mentality,” he says. They say it’s a much happier environment.”

Roffi Petrossian, horticulturalist and model/actor

Birthplace: Seattle, Washington

Years in Armenia: 5

Petrossian, a 36-year-old Seattle-born, blond-haired, blue-eyed horticulturist says the urge to reconnect with his Armenian roots came when he attended a relative’s wedding and couldn’t understand the language or the traditions.

“I wanted to know what it meant to be Armenian,” says Petrossian. In 2013, he moved to Yerevan, as part of a year-long birthright program, where he lived with a host family, studied Armenian, taught English, and volunteered by planting trees around town.

When his time with Birthright Armenia came to a close, Petrossian was not ready to leave. “I had bought a one-way ticket and soon realized it was a one-way ticket to stay,” he says.

Petrossian is now an adviser to USAID’s local Clean Energy and Water Program, and is the head gardener at Vanadzor Botanical Garden. But since moving to Armenia, he has also started working as a voice actor and model.

“I see everything with new eyes in Armenia,” says Petrossian, who is currently starring in Chanaparh (Road), a documentary on Armenian public TV. “There are rules and guidelines, but it’s similar to the Wild West, where we all start from zero and together we collaborate and build.”

Zak and Arsineh Valladian, restaurant owners

Birthplace: Washington, D.C., and Dubai

Years in Armenia: 9 and 10

Arsineh Valladian, 40, a graphic designer and photographer from Washington, DC, moved to Armenia a decade ago, hoping be part of the country’s renaissance. So was her future husband, Zak, 39, who moved from Dubai around the same time and opened a butcher shop.

The two of them met in Yerevan, got married a few years later, and started not only a family but also a business—a fast-food khorovadz (barbecue) joint that draws re-pats and locals.

They say Armenia has changed a lot since they first arrived: people follow traffic laws, and modern buildings dot Yerevan’s cityscape. However for all its growth, unemployment and poverty remain high, and corruption remains endemic.

“You have to look at the good in Armenia, not the bad,” Zak says. “You have to see the country with a positive eye and realize all that has been accomplished within less than 30 years of independence.”

Zak and Arsineh say one reason they’ve stayed is they wanted to raise their two children in the country.

“It is much more exciting, easy, and fun to parent here than anywhere else,” Arsineh says. “Everyone on the street becomes your aunt and your uncle.”

Zak echoes his wife, “There is an amazing touch of humanity still left in Armenia.”

Name: Sara Anjargolian, entrepreneur

Birthplace: London

Years in Armenia: 9

Anjargolian, 42, came to Armenia to connect to her roots—and to help local entrepreneurs connect with each other. A lawyer who used to work for the Los Angeles City Attorney’s office, she felt her work could have more impact in a developing country.

“There were these incredible projects and pockets of people who weren’t connected,” says Anjargolian, who opened a branch of Impact Hub, a global network of social entrepreneurs, in Yerevan in 2014.

She says the hub’s Yerevan branch helps connect the diaspora with local professionals, and provides a space for them to develop social-impact projects. Many of these professionals come from what Anjargolian refers to as the “independence generation,” those who grew up in an independent Armenia.

“They’re fearless and willing to put themselves in all kinds of situations,” she says.

Anjargolian says they have a lot of work to do, citing Armenia’s challenges related to high rates of poverty and domestic violence, a continued flow of outward-migration, and poor infrastructure.

“There’s a massive amount of opportunity here,” Anjargolian says, “if you’re willing to ride the waves.”