David Bowie played many roles, from Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke to a cameo on SpongeBob Squarepants to a fleeting appearance on David Lynch’s cult classic television show Twin Peaks. Bowie’s charisma and presence allowed him to shift with apparent effortlessness from character to character. One of the most outlandish roles of his career was a part that he didn’t choose: Among a certain set of Soviet citizens, Bowie became notorious as the immaculately fashionable foe of the artists’ collective and aspiring youth-movement masterminds known as Mitki.

By the early 1980s, Bowie had been an international celebrity for years. He visited the U.S.S.R. twice during the 1970s and was photographed riding the Trans-Siberian Railway and visiting iconic landmarks, including Moscow’s Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed. However, his music was not officially allowed in the Soviet Union. Media restrictions suppressed a vast swath of foreign popular music, like AC/DC and Talking Heads.

These censorship policies kept Bowie from performing publicly during his ’70s visits and kept his recordings off the shelves. However, in cities like St. Petersburg—then Leningrad—those in the know could find cassette tapes of his albums with relative ease through the shadowy network of do-it-yourself transcribers known as samizdat.

September 1984 saw the release of Bowie’s album Tonight, which included collaborations with Tina Turner and Iggy Pop.

That month, as Bowie reaped the benefits of rock stardom, a young artist named Vladimir Shinkarev eked out a meager living. Toiling in the obscurity had its advantages, however: He and others of his generation took advantage of ample time off to pursue outside interests. In Shinkarev’s case, these included painting, writing, and bonding with friends over copious bottles of cheap port wine.

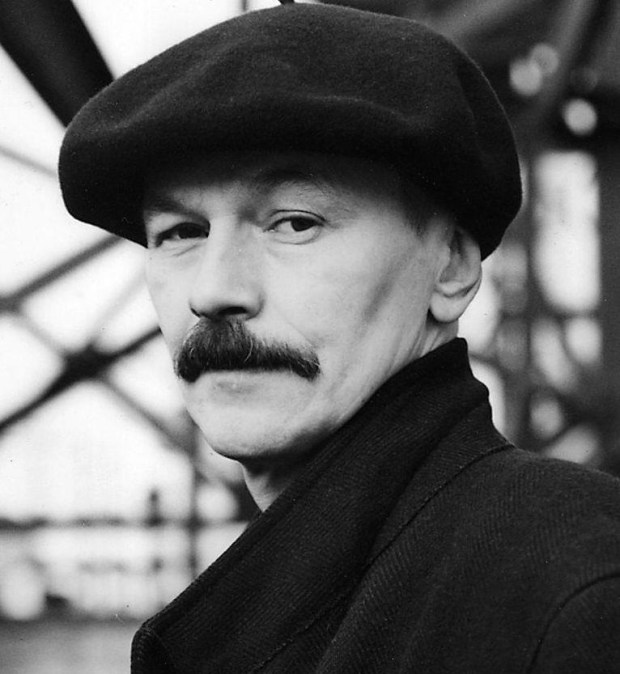

Shinkarev began work on a series of tongue-in-cheek pamphlets that distilled the aesthetic of his peers into the manifesto of a youth movement. This movement was intended to be parallel to but distinct from Western subcultures such as punk, with a proudly Russian twist. Dmitri Shagin is described in the pamphlet as not only the group’s figurehead but also its most typical member. A painter and drinking companion of Shinkarev’s with a tendency to gently defy social convention by, say, shaking hands with women and kissing men on the cheek, Shagin embodied the absurdist quality of the movement. He professed a deep love for both the imperial Russian and the Soviet militaries, especially a fascination with all things naval, while strictly rejecting violence in all forms. Thus the Mitki were born.

Released in installments via the same samizdat system that circulated Bowie’s work, the Mitki texts found a receptive audience, starting among young people in Leningrad and gaining the appreciation of countercultural types throughout much of the Russian-speaking world. Key features of a Mitki adherent as described by Shinkarev were the blue-and-white striped tel’niashka shirts typical of Russian sailors coupled with a pacifistic desire to “not defeat anyone.” As for the name, Shinkarev explained that, very simply, it’s easy to type: the Cyrillic letters that form the word Mitki lie immediately next to one another on the bottom row of the Russian keyboard. The group functioned as a loosely knit collective of largely apolitical underground artists and their supporters, hosting unofficial exhibitions and concerts until perestroika allowed them to emerge from hiding in the late ’80s.

He could wear a costume in the style of David Bowie as if it were an old torn coat.

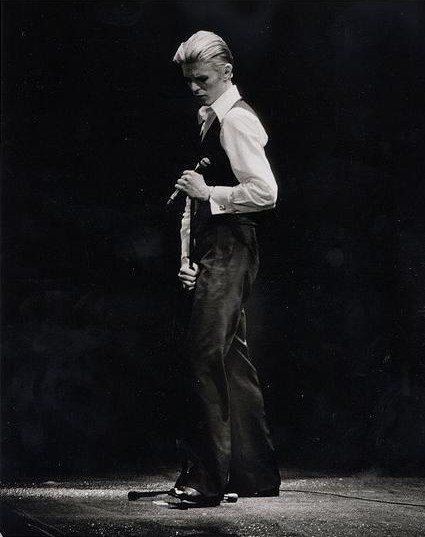

Given the humble boiler room beginnings of the Mitki, it’s not surprising that overarching rejection of Western glamour is a central tenet of the group’s philosophy. Exactly how Bowie was chosen as the principal representative of this glamour is a more complicated question. Bowie’s Thin White Duke–era flirtation with fascism—in 1975 he told an interviewer he believed “very strongly in fascism” and called Adolf Hitler “one of the first rock stars,” though he later expressed regret for the comments—may have provoked the ire of the Mitki. A group fixated on Russian military endeavors, including, of course, the costly Soviet victory in World War II, could hardly be expected to approve of a purported Nazi sympathizer. Perhaps the Mitki were aware of Bowie’s exceedingly dandyish photo shoot in Moscow and disapproved of the juxtaposition of his preening in front of Russian landmarks. Another possibility lies in the similarities between Bowie and the Russian rock musician—and Mitki compatriot—Boris Grebenshikov. As a young man, Grebenshikov resembled and sometimes dressed similarly to the dapper thin superstar; it’s possible that Shinkarev cast Bowie as villain in order to poke fun at his friend. One thing is for sure: When the Mitki decided on Bowie as antagonist, they fixated on him mercilessly.

Shinkarev describes Bowie as the absolute antithesis of the Mitki style of dress. A true Mitki man, by his description, should be so intrinsically unfashionable that “he could wear a costume in the style of David Bowie as if it were an old torn coat.” At a later point in the Mitki series, Shinkarev tells the story of an American, a Frenchman, and a Mitki Russian, all of whom try but fail to save a drowning woman who has fallen off a ship. Shinkarev says that when the American and the Frenchman enter the tale, a Mitki man should shout words to the effect of “All in all, that David Bowie! What a jerk!” Bowie serves the Mitki as whipping boy for the sins of all proud Westerners. This aside is followed by a somewhat cryptic allusion to a future treatise, to be called The Fundamental Work “The Mitki and Bowie.”

Hofstra professor Alexandar Mihailovic recounts an alternative version of the woman-overboard story, with a new ending provided by Shagin. In this variant, the antagonist—Bowie—goes forth to save the woman in a boat equipped with technological gadgets. His gear fails, and he cannot save her, but the Mitki man is able to miraculously rescue both Bowie and the woman by walking on water. He comforts Bowie by referring to him by an overwrought diminutive name: Devidushka Bauyushka.

A drawing by Mitki member Aleksandr Florensky refers to the aforementioned treatise. Made to look like a book jacket, it features Bowie in a face-off with a typically scruffy Mitki adherent and is titled The Fundamental Work “The Mitki and David Bowie,” with the unhelpful subtitle The Fundamental Work “The Mitki and David Bowie” Has Not Yet Been Written. Bowie is depicted as clean shaven and spiky haired, with a pair of headphones that betrays his reliance on technology, which the Mitki professed to scorn.

The ideal follower of the Mitki movement was obliged to flamboyantly, demonstratively resent Bowie. It’s not clear that this resentment was rooted in actual dislike, however. The Mitki were engaging in a brand of Russian humor known as stiob: parody so deep that it can be impossible to tell sincerity from insincerity. Bowie as antagonist became a tongue-in-cheek trope, one of many such tropes that were repeated ad nauseum by Shagin and his friends.

By the late 1980s, although a full-fledged youth movement had not sprung out of Shikarev’s texts, the Mitki name had enough traction to make the core collective fairly well known and successful in its native region. However, high-profile rock concerts and meetings with celebrities and political figures strained the ties among the group’s founders. Shinkarev did not appreciate the increased mainstream visibility and made his feelings clear in 2010 with a book titled The End of the Mitki. Shagin, however, continues under the Mitki name with a modified version of the original contingent of artists.

Grebenshikov, the possible impetus for the Bowie bashing, went on to develop a friendship with Bowie during the more permissive perestroika era. Grebenshikov is now considered an elder statesman of his generation of previously underground musicians, and his band, Akvarium, is among the pantheon of Russian rock gods. In 2006 he took to the airwaves to extol Bowie’s virtues on Radio Rossii, Russia’s premier public radio station. Grebenshikov acknowledged Shinkarev’s superficially adversarial depiction of Bowie but went on to proclaim, “Look closely at the writer’s brilliant device, and you’ll see that in actuality David Bowie is in his own way the alter ego of the Mitki, their spiritual leader.”

And what of Shinkarev? “David Bowie seemed to the Mitki to be a significant phenomenon and, therefore, a competitor,” he said. “The kind, relaxed, inconsistent and sloppy Mitki man—an earthy being—and the serpentine grace of the sparkling David Bowie. Of course these are antagonists, though I don’t know what Bowie himself thought.”

Ultimately, the Mitki fascination with Bowie has its roots in admiration. The unity of purpose of international counterculture proved strong enough to overcome differences in dress and political context.

A version of this article was originally published on Roads & Kingdoms on Jan. 15, 2016.