Food media sure have a thirst for trends. Those who brush up on perennial forecasts of the hottest, most anticipated culinary phenomena have likely noticed Appalachia’s spot on list after list in recent years. Mountain cuisine is a thing. Or so I’ve heard.

But in West Virginia, the only state entirely within the Appalachian Mountain chain, there’s little evidence of such a touted fad’s benefits to local cooks and farmers. More noticeable are hyped chefs in major cities paying “homage” to Appalachia through menus defined by tropes and mockery rather than respect and understanding. There is a certain story being told when a hip diner in Washington or Brooklyn serves Spam and beans in a tin can for $25 and calls it Appalachian. Whatever that story is, it’s not the one I know.

This isn’t the first time Appalachian identity has been commodified by selling false, simplistic narratives depicting an isolated, enigmatic place whose residents are allegedly poor, lazy trash. Given these familiar connotations, it’s no wonder so many Appalachian chefs approach regional branding with grave reticence.

Many of us grew up reading and hearing derogatory characterizations of items like corn liquor, red-eye gravy, and wild ramps (small, garlicky, leeklike plants that pop up on north-facing slopes each spring). As we watch these items being popularized outside the region, it’s time we recaptured our story, returning a few dollars to the hills while we’re at it.

The narratives evoked by some recent interpretations of Appalachian cuisine mirror the results of national media coverage after the 2016 presidential election, in which canned themes were tirelessly regurgitated in an attempt to solve the mystery of desperate white voters in Trump country. In the political arena and metropolitan restaurant kitchens, stories about Appalachia are, at best, drastically incomplete. Their barely surface-scratching presentation overlooks layers upon layers of diversity and social complexity that have shaped the region just as much as the geologic events that long ago carved our sharp ridgelines, deep valleys, and rolling foothills.

The food stories I know—those I’ve witnessed emerging from home kitchens, lunch pails and ramp suppers—are of strength, resilience, and perseverance; of community, resourcefulness, and perpetual innovation; of Swiss farmers, Syrian merchants, and African-American miners. These are stories of place-based pride, complicated by the troubling footprint of extractive industry, the forced removal of self-sufficient families from viable farmland, a salt industry built on the backs of enslaved workers, and the blatant theft of the continent’s most diverse forest land from Native Americans.

Implicit in a trend is a pattern of coming and going, a short-term cycle of life and predictable death. But nowhere in my people’s story is a plan to fade away. In spite of the pigeonholing that comes with media hype, West Virginians of all backgrounds are turning to regional food traditions and small-scale agriculture, breaking bread in search of economic opportunity as the stranglehold of coal slips further into the history books. Appalachian entrepreneurs are recapturing our cultural narratives at the dinner table, telling fair, just, and accurate stories through our unique food heritage, stories that could come only from this place we so proudly call home.

Next time you read about a trendy cuisine from Appalachia, don’t settle for the version presented through stereotypes or in mason jars in city bars. Head to the mountains. Take a seat. Grab a fork and listen up. This is our story to tell.

Just as disparate cultures have converged in the mountains for centuries, West Virginia’s food is more than simply a delicious combination of flavors and ingredients. In my work as a chef, I seek out overlooked stories about West Virginians’ knack for working with limited resources as part of a proud, trying relationship with the land, resulting in rich culinary heritage that stands up against any of the world’s most notable regional cuisines. When I was asked to compile a list of significant West Virginia dishes, my thoughts didn’t immediately drift to iconic foods like pepperoni rolls, slaw dogs and soup beans (not that I lack a special place for any of those in my heart). But given the chance, I’ll never waste the opportunity to highlight a few dishes whose stories have inspired me to take to the kitchen, plating up my state’s cultural heritage for the world to experience.

Mortgage Lifter tomatoes on salt-rising bread

Most farmers and gardeners I know are connoisseurs of the simple tomato sandwich. We’re known to mark two significant moments each year: consumption of the highly anticipated first and the greatly lamented last sandwiches of the growing season. The sweet, barely acid Mortgage Lifter tomato, along with two slices of fresh salt-rising bread and a generous smear of choice mayonnaise, makes for a quintessential summertime snack. But those layers of incredible flavor and the juices that run down your chin in the summertime heat contain impressive histories of farmers and cooks who embody the enterprising spirit of West Virginia’s cuisine.

In the 1930s, when M.C. Byles, a coalfield auto mechanic, had a $6,000 mortgage on his Logan County home, he had a plan to pay down his debts by developing a distinctively large, delicious tomato. After working in his garden to select plants with the most impressive traits, saving seed and cross-breeding them for years, Byles sold his seedlings for $1 each. Sure enough, his scheme worked, with greater ease than he could have imagined. The Mortgage Lifter soared to national popularity and remains one of the most sought-after heirloom varieties by backyard gardeners.

Salt-rising bread—sometimes dubbed Appalachia’s sourdough—is the prize of persistent women who worked through endless rounds of trial and error to develop a hearty loaf made from a fermented starter. Without access to commercial yeast, home bakers created leavening agents from potatoes or cornmeal kept in warm water to encourage fermentation. The result is a slightly dense, moist loaf with a fine crumb and a noticeable cheesy flavor. Once widely available in commercial bakeries, salt-rising bread is now made almost exclusively by home cooks, with a few small shops and market vendors also carrying on the tradition.

Salt trout

There’s an old-time method I use for preserving trout. It’s a simple process: coating fresh fillets with coarse salt until the moisture is drawn out and the flesh stiffens. Before the 1920s, salting of red-bellied speckled brook trout was a thing of ritual in highland communities. At some point, the tradition slipped away—not because the convenience of electric refrigerators made salt preservation unnecessary. It happened when reckless logging operations ruined high-elevation streams. To make salt trout a century ago, one needed access to a healthy supply of catchable fish, and native trout don’t survive in tainted waters.

Buried in the story of salt trout is a valuable lesson about the relationship West Virginians have with land and water. It’s about place-based cultures, unbridled greed and our forebears’ ghostly heartache that deepens each time streams are diminished in the name of extractive riches. When endless clearcuts led to fish kills high in the mountains, more than a protein-rich culinary provision went absent from kitchens and earthen cellars. For people who drew sustenance from those rivers, an essential piece of their heritage—our heritage—suddenly went missing.

When I make salt trout, I think of my great-grandmother who ran a restaurant where wild-caught fish from the Elk River frequented the menu. At the same time, I think of her husband, a logger in the Randolph County highlands, no doubt responsible, in part, for the devastation of wild trout habitat. We can’t pick and choose the ways our ancestors have affected the land through their use of resources, providing for themselves, in turn taking so much away from others. It’s a legacy that continues, firmly binding West Virginians to place. It’s a legacy that’s nothing if not complicated.

Leather britches

“Buddy, that Fat Horse, it’s a good eatin’ bean,” said my good pal Lou Maiuri, 88, when he called last August to check in on the pole beans he gave me to sow in my garden. “Now, you pick ’em at the right time, and they’ll make some real good leather britches.”

In the fall, toward the end of the growing season, the garden will be full of beans. At least it should be if we’re going to be prepared for winter. Those beans might be eaten fresh or canned or left on the vine and matured to preserve seed for next year. Many will be turned into leather britches: beans strung up inside the pods, then hung to dry in a dark, airy place. The longer it takes to dry, the more complex the flavor will be when the beans are rehydrated and slowly cooked for hours before serving. The best, most tender, umami-rich leather britches I make are simmered in rabbit stock over low heat for the better part of a day, along with a sliced onion and a couple of small pieces of salty, smoky country ham.

Lou was right; his Fat Horse beans, which originated in Roane County, make for some fine leather britches. Thanks to time-honored seed-saving traditions, there is a wide variety of heirloom beans in the mountains, with names such as Turkey Craw, Ground Squirrel, Speckled Christmas and Logan Giant (which Lou also gave me last summer). Many varieties passed down by today’s seed savers have been improved through a process of selecting for mutations and preferable traits, yet they still bear a strong resemblance to the beans that were cultivated by indigenous Appalachians before the arrival of white settlers.

Careful seed saving is critical to maintaining genetic diversity among plants and ensuring that gardens can produce enough to feed families throughout the year. But that’s hardly where the benefits of seed saving end. There’s a vital heritage aspect of every bean that’s every bit as important as flavors, textures, and harvest times. This sentiment came out last year in a conversation I had with a lifelong farmer who has grown his great-grandmother’s heirloom beans every summer since his childhood. “It’s not about the beans,” he said. “It’s always been about her.”

I look forward to harvesting Lou’s Fat Horse and Logan Giants from winding vines on tall trellises in my garden, canning jar upon jar for the pantry, then stringing up the rest for leather britches at the end of the season. And each year, when that happens, it won’t be about the beans.

Chow chow

The origins of chow chow, a lactofermented or vinegar-pickled relish, are hotly debated among Appalachian cooks and food historians. One thing everyone can agree on, however, is that there’s no use debating precisely what goes into chow chow. Head to a farmers market or roadside food stand where several varieties exist in one place and you’ll quickly see why. Each recipe varies from farm to farm, kitchen to kitchen, often determined by the crops in abundance at the end of the growing season. Chow chow’s ingredients are sometimes considered the garden’s leftovers, but in a thrifty culture dependent on making food stretch through the winter, cooks and gardeners can’t afford to waste precious vegetables. Many chow chow recipes are heavy on ingredients like cabbage, onions, and peppers, while my grandmother’s recipe consists almost entirely of green tomatoes. My favorites contain bases of chopped root vegetables, such as spicy turnips and radishes, flavored with maple syrup, turmeric, mustard seeds, and fresh garlic.

The tradition of canning and storing foods like chow chow is most closely associated with farmsteads and large backyard gardens. But canning and preserving have also played vital, underappreciated roles in coal camps, helping shape West Virginia’s tumultuous labor history.

When organized miners of the early 20th century would strike, walking off the job seeking better wages or safer working conditions, they willingly stepped into situations of grave financial uncertainty for weeks, months, sometimes even more than a year. Prolonged periods without pay hampered miners’ ability to buy food from company stores, necessitating other ways to provide for their families in order to sustain the strike. Led by coal camp women—often European immigrants who came from agricultural backgrounds or African-Americans transitioning from sharecropping arrangements in the South—food preservation efforts allowed for extended strikes, thereby increasing the miners’ collective leverage against the mine operators as time went on. Typical gardens in the segregated coal camps were tiny, generally confined to minuscule yards of company houses. Just as miners were organizing for collective power, their spouses joined with other households to turn an array of meager vegetable plots into a prolific instrument of sustenance and resistance. Mining families were known to break down barriers of segregation, sharing resources in solidarity across racial, religious, and ethnic lines to win historic labor victories with national implications.

The way food and a sense of self-sufficiency empowered striking miners continued well beyond the mine wars of the early 1900s. Anticipating a strike in the 1970s, United Mine Workers representative Dan Burleson said of mining families’ preparations, “Everybody I’ve talked to has a little garden, and their wives are canning food.”

Chorizo

Largely forgotten in West Virginia’s immigration history are thousands of Spanish laborers who arrived seeking manufacturing work in Harrison County during the first decades of the 20th century.

For immigrants from coastal regions like Asturias in northern Spain, certain dishes were either lost or adapted to ingredients available in West Virginia. Not all culinary traditions underwent drastic changes, however. Pork, salt, sugar, and spices could be easily acquired in the Mountain State, and recent Spanish immigrants weren’t about to let their country’s proud charcuterie heritage slip away. Several varieties of Spanish chorizo, as well as morcilla and longaniza, were cured in backyard smokehouses, some of which still stand in communities like the former factory town of Spelter. Relatively few Spanish descendants make traditional sausage in West Virginia anymore, but for those who remain, their recipes have withstood the test of time. When my neighbors returned from a vacation to their ancestral home, they enthusiastically recalled the links they sampled along the Asturian coast tasting exactly the same as the generations-old family recipe they had been tasked with stewarding.

Today another wave of Spanish-speaking immigrants, not from Asturias or Andalucia but from Mexico and Central America, are shaping Appalachian foodways. Once again, chorizo—albeit of a different variety from the smoked, cured links introduced by the Spaniards—is being widely enjoyed in West Virginia, finding its way onto grocery store shelves and restaurant menus in urban and rural communities alike.

Vinegar pie

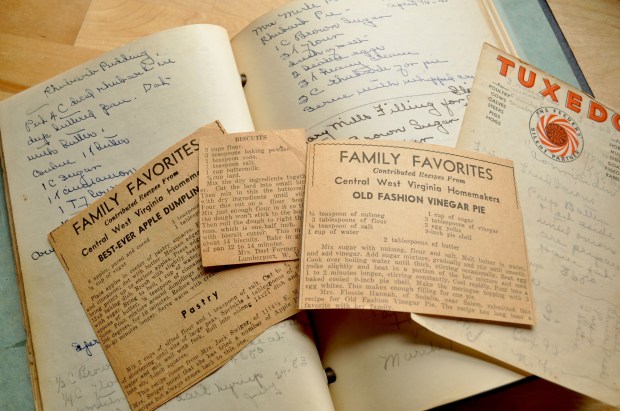

In the early 1930s, Flossie Hannah sent her vinegar pie recipe to the editor’s desk at The Clarksburg Exponent, a local newspaper that, at the time, ran a series called Family Favorites: Contributed Recipes From West Virginia Homemakers. I’m glad she did, since her version is the one I stick to today. Her recipe, along with dozens of others from home cooks in surrounding communities, was clipped from the newspaper and included in a vast collection here at Lost Creek Farm curated over the course of several decades.

Vinegar pie was designed to mimic a lemon pie at a time fresh lemons and their juice were hard to come by. In an endless quest to develop practical solutions born of necessity, rural cooks resorted to vinegar, often homemade varieties, as the perfect citrus substitute. In Scott’s Run, a diverse mining community near Morgantown, vinegar pie was documented and attributed to traditions of African-American cooks. A cookbook from the town of Helvetia, a Swiss community where my great-great-grandparents settled in the 1880s, contains a recipe in which the vinegar is a substitute for milk rather than citrus. Hannah’s recipe calls for a touch of nutmeg, elevating vinegar from merely a tart replacement for citrus to something more fragrant, bearing a surprisingly close resemblance to lemons.

I don’t know much about Hannah other than the fact that she was born in 1893 and was buried near her home in Salem, just outside Clarksburg, when she died in 1975. I may never discover much more about her, but I like to imagine what she would think about all this—about vinegar pie and other regional dishes becoming popular in major cities, about her recipe being used to exemplify the creativity and ingenuity of home cooks in West Virginia. I like to think she would be proud to see her recipe being spread, just as she shared it and someone else probably did for her.

I hope she would be happy to know how often I point to her recipe as proof that West Virginia’s food heritage, unlike a short-lived trend, simply refuses to die.