On a recent sunny spring afternoon, I was cycling near my home in Berlin with my partner, Cordula, and our 6-year-old son. German law requires children under 9 to ride their bikes on the sidewalk and allows one adult supervisor to ride in front or behind them. Since there were almost no pedestrians around, Cordula rode slowly in front while I brought up the rear. Suddenly, I heard a gruff voice from across the street.

“One parent only is permitted to accompany a child on the sidewalk. The other must ride in the street.” I looked up to see an elderly, red-faced man, poised on the pavement, hands on his hips.

“I repeat. One parent only is permitted to accompany a child on the sidewalk. The other parent must ride in the street.”

And, like a mantra, a third time: “I will say it once more. One parent on the sidewalk. The other in the street.”

I could no longer restrain myself. I turned to him, saluted, and exclaimed “Jawohl!” It’s a highly loaded word here in Germany, occasionally used to celebrate a goal on the soccer field but more closely associated with the German army during World War II.

Cordula, who is German, pointed out that the elderly man was right: We were breaking the law. And by invoking World War II–era language, I had insulted him and her, she said. Chastened, I quickly steered off the sidewalk and completed the bike journey in the street. But the episode reminded me of the cultural dissonance I often feel living in Berlin, where a strict adherence to rules and order is ingrained, particularly among older generations.

As a born and bred New Yorker, used to the raucous, in-your-face informality of my hometown, I’ve never quite gotten used to it.

Something similar happened one recent Sunday morning, as I walked to a bakery near my home in the Wilmersdorf district. The light was red on Berlinerstrasse, the wide commercial avenue near my apartment, but—as there was no vehicle in sight—I strode across the deserted street. The moment I stepped off the curb, an older woman across the street glared and screamed, “Rot!” (Red!)

Startled, I ignored her and kept walking.

“Rot!” she again exclaimed. I’ve spoken with jaywalkers—all of them foreigners—who have endured more vituperative reactions. One, who crossed against the light in front of a toddler, was called a murderer by a passer-by—the reasoning being, apparently, that she was setting a malignant example that would one day send the little one plunging into traffic and certain death.

These clashes are part of daily life here. There was the postal clerk who, when I approached her for stamps, admonished me to remove my helmet. There is the elderly woman in our apartment building who chastises us for every infraction—leaving our son’s bicycle in the hallway, failing to crush the cardboard boxes in the building’s recycling bin, using too much garlic and smelling up the hallway. I don’t think this Frau has ever forgiven me for duzen-ing her (addressing her with the informal du instead of Sie) when I first moved in. Cordula has come to refer to her as the Blockwart; another loaded term, it refers to the spies who enforced rules and sometimes reported on their neighbors during Germany’s darker times.

I’ve never quite made my peace with this aspect of my adopted city. But Berlin, where I have resided on and off for the past 11 years, is changing. Younger Berliners are more apt to break from protocol—crossing streets against the light, riding bikes on the sidewalk—as long as there’s no danger of harming anyone. Some Berliners might see this as a slippery slope toward chaos, but I find it refreshing. And on a deeper level, the gradual transformation of Berlin over the last decade into an international capital has altered the city’s look and loosened its atmosphere.

Every time I take the U-Bahn, I’m struck by the variety of the faces—Africans, Arabs, Turks, Afghans, Chinese, Swedes, Russians, and Americans, conversing in a great babble of languages and mingling their customs and behaviors with those of the native Germans. The other evening, while heading to trendy Kreuzberg for dinner, I forgot my iPhone at home. Unsure of the restaurant’s address, I approached four people on the train and platform for help; not one was a native German speaker.

I can’t imagine that happening when I first arrived, as bureau chief for Newsweek in 2000. Berlin has become a cultural crossroads, a true global city.

The city’s transformation is striking. Last week I visited “Thai Park,” a grassy field off Fehbelliner Platz in Wilmersdorf, where dozens of Thai women, many of them wearing wide-brimmed straw hats, knelt over woks and prepared some of the best pad thai, fiery papaya salads, and curries that I’ve ever eaten. It was an exact replica of a sidewalk food bazaar in greater Bangkok. Though it operates quasi-legally and authorities have threatened repeatedly to close it down, it draws thousands of mostly young Berliners every Sunday.

Sometimes on warm evenings, I’ll take the U-Bahn east to gritty Neukölln to meet an Iraqi friend for a meal and smoke shisha at one of the dozens of Iraqi and Syrian restaurants that line nearby Kolonnenstrasse. The area, long known for its Middle Eastern flavor, could be mistaken for a part of central Baghdad—albeit one that is a whole lot safer.

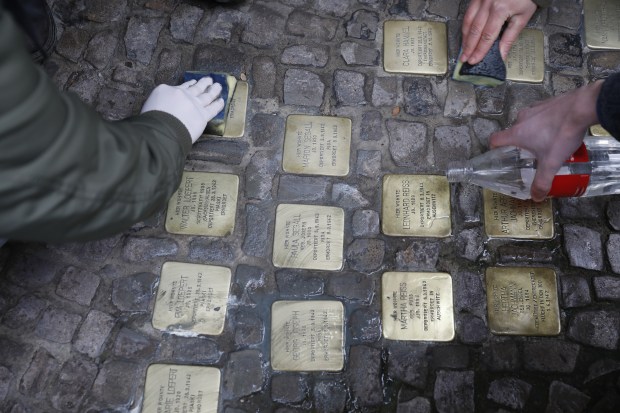

My neighborhood, Wilmersdorf, is the heart of the former Jewish quarter of the city. Stolpersteine—small brass plaques embedded in the pavement, usually in front of apartment buildings, that commemorate Jewish people who lived there—are ubiquitous. They note the date of each person’s arrest, deportation, and death, often at Theresienstadt or Auschwitz.

We chose our neighborhood for a variety of reasons: its proximity to both the city center and the swimmable lakes and forests of the far west, its easy commuting distance to a good public school, and the many playgrounds and quiet, leafy streets that give it almost a suburban feeling in the heart of the city.

But heterogeneous Wilmersdorf is not. Unlike, say, Mitte and Kreuzberg, where every other resident seems to be from elsewhere in Europe or the United States and the clash of foreign languages is invigorating, it’s rare to hear anything but German spoken here.

I’m the only foreigner in our apartment building, and for some, I’m an object of mild curiosity. The elderly couple on the floor below us gets a kick out of turning over to me the packages from The New York Times and other U.S. publications that the delivery man entrusts to the two of them when I’m out. They often ask whether I think Donald Trump will survive as president until 2020. The middle-aged couple across the hall regales me with tales from annual road trips across America; one year the pair visited the Deep South, another the West Coast.

Though living in Wilmersdorf can feel like a more traditional Berlin experience, at times it reinforces my feelings of being an outsider. (It is one, granted, that I perpetuate by spending much of my time either sealed off in my home office writing or reporting from around the world.)

But even here, in one of the pockets of old Berlin, the texture of life is changing. One day last spring I returned to my apartment building after a morning in Mitte and, and as I opened the entrance door, noticed someone on the floor. A Muslim man clad in a djelabiya knelt on a prayer rug that he had thrown down in a corner and was deeply engaged in his midday prayer. I don’t know who he was or what he was doing in our building, but it really didn’t matter. I tiptoed past him and, smiling, ascended the stairs.