When fiddler Jourdan Thibodeaux talks about the cultural collisions that influence the rural South Louisiana sound, he gets excited.

Consider that the grandfather of Cajun fiddle, Dennis McGee, was of Irish descent, he says, and that French-Louisianian musicians play the accordion—a German instrument—over West African beats.

“It’s such a mélange of all these different people coming together,” he marvels. “There’s so many things that we title as Cajun that’s completely, completely rooted in things that’s very distant from Acadie.”

In a region known to the world as Cajun country, the Cajun identity’s dominance has taken hold only during the last few decades. Creole scholars say it has supplanted the Louisiana Creole moniker that people there—including the people now called Cajun—used to distinguish their blended Latin cultures from Anglo-Americans’.

Thibodeaux and others say “Creole” is a more inclusive representation of Louisiana’s storied culture.

“It’s a melding of cultures,” says Thibodeaux, who says he has European, African, and Native American roots. Of his four grandparents, one is of Swiss descent, and the other three are of Acadian ancestry.

“I’m as Cajun as you can be,” he says. “But at the same time, to try and act like Cajun isn’t a subset of Creole is just cuckoo. I mean, we’re definitely Creole people.”

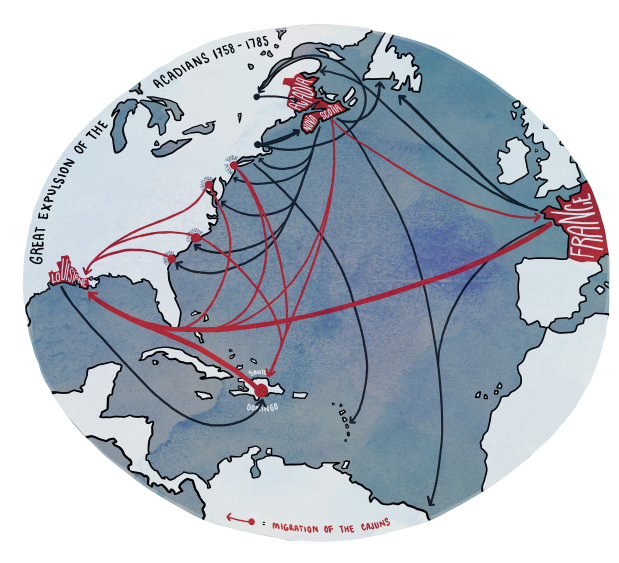

Cajuns are the Louisiana descendants of the exiled Acadians, and scholars say they identified as Creole well into the 20th century. They say postbellum social reclassifications changed the Louisianian idea of Creole. Today it’s often propped up as a racialized counterpart to Cajun, and the idea that Cajuns are white Louisianians and that Creoles are black remains widespread, even in South Louisiana.

Christophe Landry, an academic who identifies as Creole, says “Creole” used to refer to a culture, not a race. “It was very much anchored in cultural identity, closely linked to language,” he says, adding that in the 18th and early 19th centuries, Louisiana Creole referred to non-English-speaking Catholics of French or Spanish descent. But this distinction altered after the Civil War.

Elista Istre, another Creole historian, says antebellum Louisiana was a three-tiered society: elite whites, free people of color (who made up less than 3 percent of the population and could be Creole or enslaved people who had bought their freedom) and enslaved Africans. Whites and slaves each accounted for almost half of Louisiana’s population of more than 700,000 before the war, according to the 1860 census.

She says the end of slavery altered this social structure. White elites began to associate Creoles of color—including the descendants of about 10,000 Haitian Creoles who arrived in South Louisiana after the revolution—with the emancipated slaves they saw as below them.

“Whites, who had been associating and intermarrying with blacks for decades, at this point no longer want to be associated with the term ‘Creole,’” Istre says.

Her ancestors, she says, were among those who shed that identity and began to call themselves Cajun. “The term ‘white Creole’ started dropping out of usage, especially in the prairie and swamp areas,” she says, while people of color held on to “Creole.” Jim Crow laws enacted in the decades after the Civil War compounded the divide, forcing blacks and whites into different schools and churches.

Rebecca Henry, a Creole folklorist who grew up in rural St. Landry Parish the 1940s, says lighter-skinned Creoles often discriminated against darker-skinned Creoles like her.

“I went to school with [lighter-skinned students] who walked on one side of the street, and we walked on the other side,” she recalls.

She says the light-skinned Creoles shed the identity altogether.

A lot of the locals felt that these people were imposing a new sort of French onto them and, with that, a new sort of identity.

Then came the 1960s and Louisiana’s Francophone renaissance. It was marked by a government-supported shift toward reintroducing the French language in the state’s schools and promoting the state’s French heritage, all at a time when Landry says identity movements were taking hold around the globe.

“That was the moment when there were all these ethnic movements,” including for the Irish, Italian, and German identities, along with the U.S. civil rights movement, he says. “And so Louisiana Creoles and Cajun very much fit in that story.”

In 1968, Louisiana lawmakers started an effort to reverse the collective loss of the French language. They created the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), an organization dedicated to growing the state’s Francophone communities by helping establish immersion and language-building programs. Today CODOFIL says 26 schools in eight parishes offer French immersion programs.

But Landry says CODOFIL, led by white Creoles, stumbled in its efforts to bring French education back to the state. The group brought in French teachers from places like France, Quebec, and Belgium, and their language did not mirror Louisiana’s regional dialect.

“A lot of the locals felt that these people were imposing a new sort of French onto them and, with that, a new sort of identity,” he says. Light-skinned, French-speaking Louisianians reacted by clinging to the Cajun identity, he says, and rejecting what they began to perceive as the uppityness of the Creoles in the Francophone movement.

“It was better to be called Cajun than to be called black,” he says.

The Cajun narrative continued to strengthen, and in 1971 the State Legislature designated 22 southwestern Louisiana parishes Acadiana.

But some objected to the characterization as just one piece of Louisiana’s rich culture. “The thing, the unifying element, is whiteness and French background,” Landry says, and the Creole culture that’s common to Louisianians—regardless of whether they claim an Acadian bloodline—is overtaken by the Cajun branding.

Some travel bureaus now include references to the Creole identity in their promotional materials, although it’s portrayed as distinct from Cajun. In 2008, Lafayette’s Festival Acadiens added “et Créoles” to its name, even though Istre says Creole musicians have been performing at the annual music, food, and crafts festival since it began more than three decades ago.

Thibodeaux avoids referring to “Cajun” or “Creole” when he talks about his music, which he instead bills as “Louisiana French.”

“Cajun is good, and I love it, and I’m proud to be a part of that,” he says. “But at the same time, we’re part of a much bigger thing.”