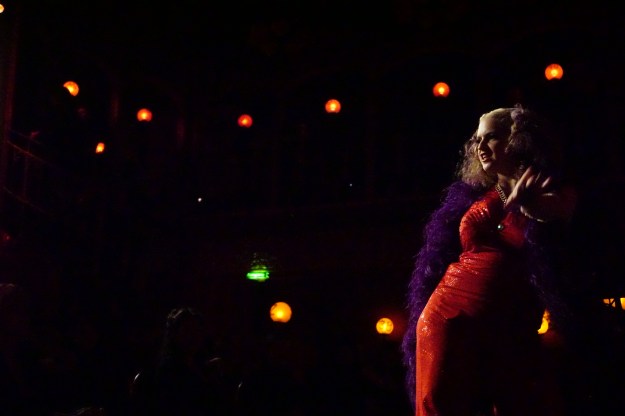

The bar is busy, tables are full, the lights are dimmed, and burlesque dancers are about to go onstage at Theater im Delphi, a converted silent movie theater from the 1920s. Cabaret classics play on the loudspeakers, and bartenders serve Prohibition-era cocktails to the growing crowd. It’s the gala night of Berlin Burlesque Week, an annual festival that launched in 2016 and drew close to 1,500 people this year, and everyone looks as if they just walked off the set of Cabaret.

“Every year we attract bigger crowds and get to be in bigger venues,” says Lolita Va Voom, one of the event’s organizers. “Part of the reason is the popularity of cabaret, which has been rising pretty steadily in Berlin for the past years, and part of it has to do with the rising [interest in] the Weimar era.”

The Weimar Republic—an unofficial designation, from the town where a new German government was formed in the wake of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s abdication after World War I—lasted from 1919 to 1933. It was an era marked by hyperinflation, political fragmentation, rising nationalism, and the rise of Adolf Hitler. But it was also a golden era for artistic exploration, scientific discovery, and personal freedom. And Berliners are increasingly nostalgic for the era’s cultural riches.

“The aesthetics really appeal to people in the digitized world. A lot of us are longing for a more glamorous and less digital age,” says Brina Stinehelfer, who runs Delphi with her partner, Nikolaus Schneider.

The allure has gone global. Last year Babylon Berlin, a crime drama set in Berlin during the Weimar years, was a runaway success at home—more than 1 million Germans tuned in when it premiered—and it has been sold to dozens of international TV markets for distribution (including Netflix in the U.S.). Several scenes were shot at the Delphi, a cultural hotspot frequented by celebrities of the era like Marlene Dietrich and Fritz Lang.

This year the Berlin International Film Festival held a retrospective of Weimar-era films, screening classics like Spring Awakening, a 1929 silent film about adolescents coming into their sexuality, and The Other Side, a 1931 German film that imagines World War I through the eyes of British soldiers.

Venues like Prinzipal, Wintergarten Berlin, and Bar Jeder Vernunft host regular cabaret nights, and galleries like Berlinische Galerie have dedicated spaces for Weimar-era art. (The Bauhaus school, which produced some of the era’s most iconic art, turns 100 next year.) And a new English translation of Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, widely considered the great novel of the Weimar years, was released this year—an indication that this fascination with the Weimar years is not limited to native Berliners or even German speakers.

Stinehelfer says that at least for Germans, the interest in the era goes deeper than movies and nights out on the town. “People of the Weimar years were dancing on a volcano,” she says. “Things were changing very rapidly politically. There was a feeling that something big was happening. When you look around today at Europe and the States and consider what is happening in the sociopolitical landscape, there’s a similar sentiment.”

Many Germans. particularly in Berlin, looked on aghast as Britons voted to leave the European Union and Americans elected Donald Trump as president. In September, Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD)—whose candidates campaigned on immigration restrictions and an anti-EU platform—became the first populist right-wing party since World War II to cross the 5 percent threshold and enter the Bundestag. Meanwhile, Berlin remains one of Europe’s most progressive, culturally relevant cities. “That tension is what’s fueling the [interest in] the Weimar years,” Stinehelfer says.

Germans aren’t the only ones fascinated by Berlin’s Golden ’20s.

Brendan Nash is a British tour guide who specializes in the novelist Christopher Isherwood’s time in Berlin, from 1929 to 1933. Nash moved here in 2008 with his partner, John; like Isherwood, they were looking for a more affordable, creative, and adventurous life in a city offering more personal freedoms.

The couple settled in Schöneberg, a neighborhood known for its art scene and vibrant LGBTQ community, near where Isherwood lived. The author’s novels chronicle the poverty and promise of Berlin in the 1920s. As the country grappled with a shattered postwar economy, young artists and bohemians from across Europe flocked to the city, seeking out cheap rents and personal—not least sexual—freedoms. It was in the brothels, gay bars, opium dens, nightclubs, and cabarets of Schöneberg that Isherwood chronicled the hedonism of the Weimar years.

(The era is also noted for scientific discovery: In that time, nine Germans were awarded Nobel Prizes, among them Albert Einstein, who was forced to flee in 1933. And the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld opened the famous Institute of Sexology in Berlin in 1919.)

Nash takes small groups of tourists and Isherwood fans to an apartment where the writer once lived, the site of the legendary nightclub Eldorado, and the former cinema (and current nightclub) Neues Schauspielhaus. He says requests for his tours, from Germans and foreigners alike, have grown in recent years.

“People are paying more attention to the Weimar era and the interwar years because they realize that this is not dry history,” he says. “Just like in the Weimar Republic, we’ve gone from a period with prosperity and freedom to one where right-wing populist parties are on the rise, the governments are fragile, and people are saying things in public they wouldn’t have dreamt about saying just a few years ago.”

Nash, who is writing a novel set in Berlin during the period, says that, despite political anxieties around the world, the city is a haven for many, just as it was during the Weimar years.

“Berlin became a center for the gay, artistic and scientific scenes in the 1920s because it was a place where people could afford to take risks and be creative. It’s a similar situation today, and one of the main draws of Berlin is still that you can move here, have your personal freedom, and be who you are without it costing you an arm and a leg.”

Joseph Pearson, the author of the book Berlin, echoes that sentiment. “Like in the Weimar years, Berlin today is a place where people go to be the person they can’t be back in the small towns they come from,” he says, adding that part of the reason young Germans are celebrating the culture of the Weimar years is that they want to reclaim that part of German history. “Germans have spent a lot of time thinking about who they are in relationship to [the Holocaust]. They go back to the Weimar Republic, which shows a different part of what it means to be German.”

Nash agrees that the fascination with the period is a celebration of its progressive mores. But, he says, “in addition to the politics and the cultural fascination, people like that era because it’s fun to dress up.”