Hong Kong is a city of contrasts. East meets West. The mountains and the coast. A cramped concrete jungle set against open green spaces. For better or worse, the city is always evolving—it can be all but unrecognizable from one year to the next. Its people are paradoxically nostalgic for the near past while rushing forever breakneck into a new and improved future. To truly understand it, you have to experience every level of it. Here’s your starter kit.

What to watch:

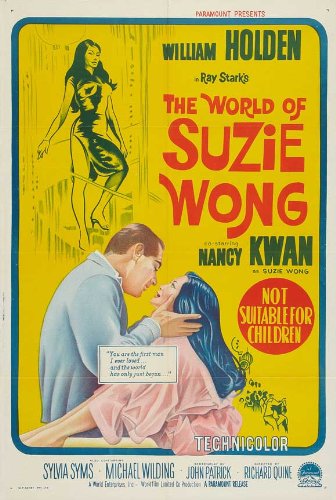

The World of Suzie Wong, directed by Robert Quine

There aren’t many movies that depict Hong Kong during its years under British rule. The World of Suzie Wong (1960) presents a Hong Kong that no longer exists: colonial buildings set right on the water, rickshaws racing down the streets, and ancient trams rumbling down the harborfront. The hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold story is schmaltzy and cliched, and the portrayal of an “exotic Orient” can be disturbing, but it reflects the era, and it’s worth it for the lush urban panoramas and close-ups of everyday street life.

Fist of Fury (aka The Chinese Connection), directed by Lo Wei

Bruce Lee was Hong Kong’s finest movie star until his sudden death in 1973 at the age of 32. Lee’s Hollywood debut, Enter the Dragon, is one of his most internationally recognized films, but Fist of Fury, filmed in Macau and Hong Kong, resonates with locals. Set in Shanghai during World War II, the movie not-so-subtly references Japanese aggression during the era and China (and Hong Kong’s) desire for justice: Lee’s character, Chen Zhen, avenges his master’s death, obliterating a Japanese dojo with his chopsocky skills. It’s a brutal and bloody kung-fu flick, full of tense face-offs and slow-motion fight scenes.

A Better Tomorrow, directed by John Woo

Some Hong Kong movies could make you believe that gunfights happen frequently in the city. They don’t—Hong Kong has strict gun laws and relatively low crime rates. Woo’s highly acclaimed, if violent, A Better Tomorrow (1986) centers on two brothers on opposite sides of the law: one’s a counterfeiter, the other’s a cop. Showcasing the director’s frenetic style and stylized action sequences, the movie broke domestic box office records, popularized the heroic-bloodshed genre, and inspired remakes.

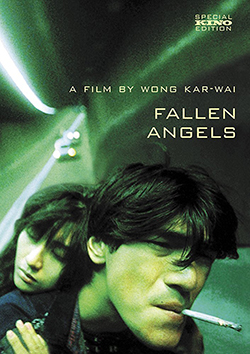

Chungking Express and Fallen Angels, by Wong Kar-wai

The days leading up to the 1997 British handover of Hong Kong to China were tense, and director Wong Kar-wai captured that anxiety in this pair of dreamlike neon-lit films. The more internationally acclaimed Chungking Express (1994) is two separate tales, about police officers mulling over past loves and finding new ones and set against the city’s brightly lit, hectic streets. Fallen Angels (1995) casts a grittier light on the city, here teeming with criminals, vixens, and weirdos. In retrospect, they’re the perfect pre-handover pair: one exploring love and light, the other examining darkness and depression.

Election and Triad Election, directed by Johnnie To

Ask most locals and they’ll tell you that triads—Hong Kong’s mafia—really run the city. For years on-screen representations of the triad societies were nothing more than over-the-top bloodbaths, rarely resembling the Machiavellian workings of Hong Kong’s organized crime. The Election films (2005 and 2006) changed that by depicting the power struggles surrounding an annual triad-leader vote. It’s shrewd political satire of the city’s post-handover elections: Throw in a false democracy, raging capitalism, and the foreboding influence of mainland China, and you have all the makings of modern Hong Kong.

Know before you go:

1. Don’t call us China.

Even though Hong Kong is technically part of China, we have a complicated relationship. Hong Kong was a British colony from 1847 to 1997, when sovereignty was handed back to China. Like Macau, the city is now a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of mainland China, but we have our own laws, official languages (Cantonese and English), currency, and passport. Hong Kong’s complete transfer back to China is scheduled for 2047, at which point the city will fold completely into the mainland—and no one knows what will happen to our freedoms. Many argue that our autonomy is already eroding. Despite—or maybe in spite of—the impending change, residents are incredibly proud of our distinct culture and heritage. So don’t call us China—yet.

2. When talking politics, tread lightly.

Politics are a touchy subject in Hong Kong. Politicians in Beijing aren’t delivering on their promises, and many citizens complain that their local officials are corrupt and ineffective. Locals, who enjoyed Western-style democracy for over 150 years, bristle when Beijing asserts its power. In 2014 Beijing announced it would vet candidates for Hong Kong’s chief executive election, and hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets, all but shutting down the city. Some residents are calling for Taiwan-style independence (something China will never accept); others are fighting for a stronger democratic institutions. Most would rather avoid the subject altogether.

3. Beat the heat.

Hong Kong isn’t as steamy as our neighboring cities (looking at you, Singapore), but in the summer temperatures regularly hover around 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Try to avoid visiting during the springtime typhoon season—and absolutely stay away during the scorching summer. Come during the fall, when sunny days yield to cool nights. In the spring, Art Basel and the Hong Kong Sevens, a rugby tournament, draw tens of thousands of visitors to our already cramped city—join the crowd at your peril.

4. Use public transportation.

Public transportation is cheap, efficient, and clean. The underground Mass Transit Railway (MTR) is modern and extensive, reaching the border with mainland China. Double-decker buses and minibusses are also a great way to travel around the city, but our favorite modes of transportation are old-school. The Star Ferry, which dates back to 1880, offers stunning vistas as it ushers you between Hong Kong Island and neighboring Kowloon. The century-old tram system is perhaps the best deal; it costs about a quarter and travels the entire length of Hong Kong Island.

5. Go downtown.

When the city government launched the Keep Hong Kong Clean campaign in the 1970s, hawker stalls and dai pai dongs (open-air cooked-food stalls) were moved to dedicated centers. North Point’s Java Road Cooked Food Centre is home to Tung Po, whose squid-ink pasta is a must; and Happy Valley’s Wong Nai Chung Cooked Food Centre has earned the nickname “tycoon’s canteen” for its high-end seafood stalls.

6. Explore the islands.

Most people think of Hong Kong as a concrete jungle, but there’s an actual jungle out there too! Over 70 percent of the city’s surface is undeveloped green space. Hong Kong’s outlying islands are the best way to explore that space, and most of them are easily accessible by ferry.

Thirty minutes from Hong Kong’s main port, Lantau Island is home to the serene Tai O fishing village and several hiking trails. Lamma is a laid-back island of hippies, vegan restaurants, and white-sand beaches. The small island Cheung Chau has a great selection of seafood restaurants and leisurely bike paths.