In 2003, when asked to explain the appeal of his hometown, Berlin, Mayor Klaus Wowereit, a charismatic progressive, had a simple, confident answer: “Poor but sexy.”

His ambitious rebranding efforts to make Berlin a world-class city yielded remarkable results. Although the official motto became “Be Berlin,” Wowereit’s declaration helped attract an influx of artists, creatives, and, in more recent years, startup founders and tech investors.

The city’s reputation as the unquestioned capital of European cool is, at this point, universally known. However, it has come at a cost. Some say the city is losing its mystique. Gentrification threatens the livelihoods of immigrants and other residents who have called Berlin home for generations, and pessimists warn that the city is becoming polished and soulless—a “generic hipsterville,” writes Bloomberg’s Leonid Bershidsky.

Berlin today could not be more different from Berlin in the late 1970s. Haunted by the psychological and physical scars of Nazism, isolated by Cold War anxieties, and desperate for economic stability in the wake of a recession, it was a city aware of its fragility. Divided by a wall and surrounded by international troops, there were two Berlins—East and West—within sight of each other but without hope of engaging in anything close to meaningful communication until 1989.

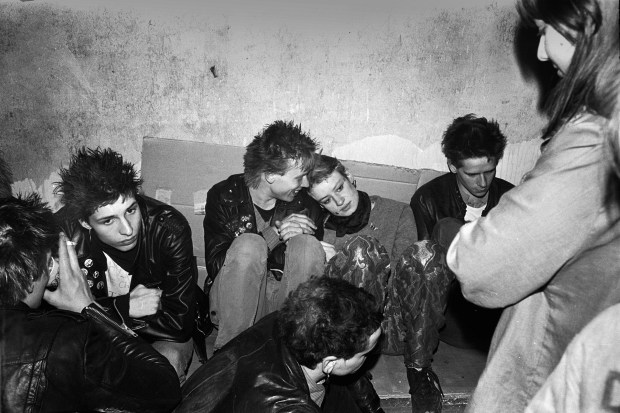

Against all odds, this backdrop of paranoia gave rise to a thriving underground cultural scene in West Berlin, one whose influence lasts to this day. Berlin became a bold, forward-thinking center of experimentation. The city presented tremendous opportunities in the form of neglected but subsidized housing left over from the war. Empty warehouses and other large spaces—abandoned by the Nazis, Soviets, and Americans—were available to anyone ambitious or foolish enough to purchase or claim them. The island-like West Berlin lured young punks and squatters (both German and foreign) with its intoxicating disorder and frenzy. The city emerged as a refuge, one tolerant of alternative attitudes, lifestyles, and ideologies.

Here are three tracks that define this era of wild abandon:

David Bowie, “A New Career in a New Town” (1977)

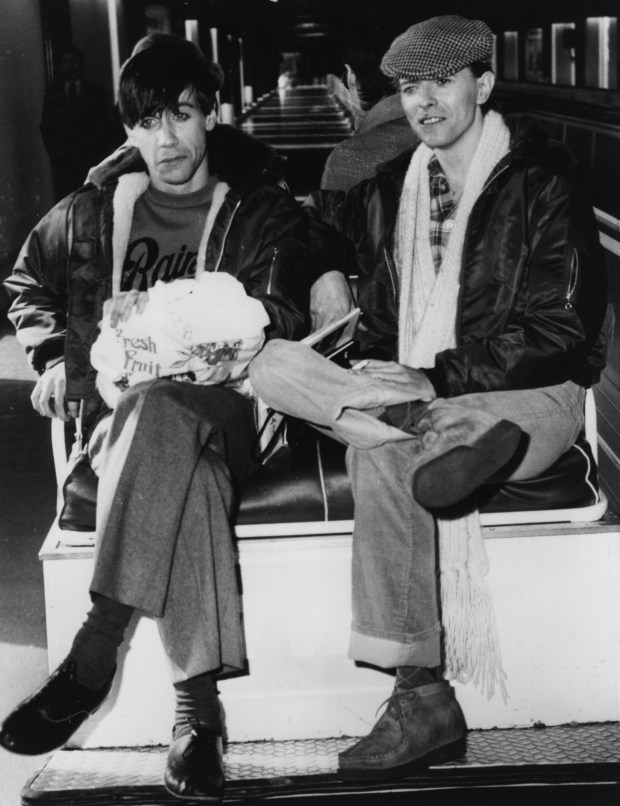

David Bowie was “enveloped in a cocoon of cocaine and messianic self-importance,” according to journalist Mick Brown, when he fled Los Angeles for Berlin in 1976. Overwhelmed by the pressures of fame and on the verge of mental collapse, Bowie craved rejuvenation, a return to normalcy, and a radical change of pace. His stint in the city began with a characteristically theatrical bang. One night, according to author Rory MacLean, with Iggy Pop sitting in the passenger seat, Bowie drove at full speed in an underground parking lot while screaming at the top of his lungs that he wanted nothing more than to end his own life.

After moving to Berlin’s edgy Schöneberg district, Bowie began his remarkable healing process. He found solace in a city that wasn’t preoccupied with him. He immersed himself in the seedy cultural scene and, though Berlin had a reputation for druggy decadence, managed to expunge his addictions.

Bowie’s work during his Berlin period was an important contribution to the city’s culture and creativity. This track reflects his newfound stability and optimism. Though an instrumental tune, it is decidedly autobiographical in tone. The two-part song is an exercise in genre-hopping. In the first half, harmonic, ambient layers of synthesizer and a detached drum pulse point to the influence of Kraftwerk, the Düsseldorf-based electronic music pioneers. In the second half, live instruments make their appearance (most notably Bowie’s harmonica, an instrument not heard on any of his records in years, used to great symbolic effect here). It is important to note that these are not clashing musical or personal visions. This is the sound of a man coming to terms with an occasionally grim past while wholeheartedly embracing the uncertainty of the future.

Tangerine Dream, “Kiev Mission” (1981)

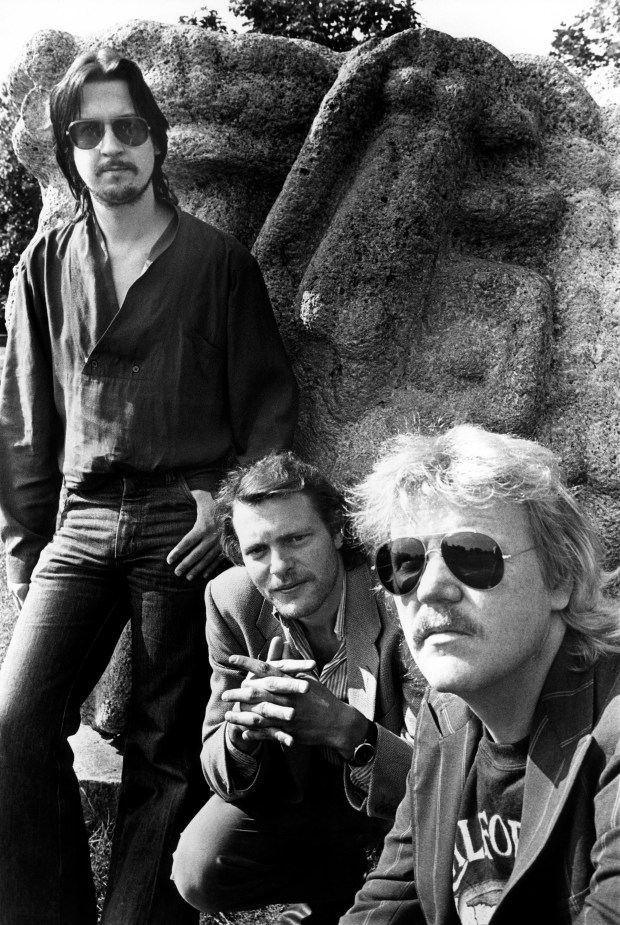

Without Tangerine Dream, a band unfairly pigeonholed as krautrock by the British music press, electronic music as we know it today would be nearly inconceivable. Led by Edgar Froese, the group’s leader and only ever-present member, the Berlin-based Tangerine Dream altered its sound over the years but remained at the forefront of boundary-pushing outsider music that blurs the lines between tradition and innovation.

In the same way that Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground called Andy Warhol’s Factory home during the late 1960s, Tangerine Dream used Berlin’s short-lived but highly influential Zodiak Club as a testing center for soundscapes equally indebted to the grooves of James Brown as they were to the musique concrète of Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Froese called Berlin home for most of his adult life until he died in 2015 at the age of 70. Froese, whose father was killed during the Holocaust, came of age during the Cold War. “Privations on all levels of a daily life were normal,” he told British online magazine The Quietus.

This emotionally heavy track, though beautiful, begins by crafting a horrifying, detached atmosphere. The distorted blasts of synthesizer that kick it off sound simultaneously industrial and organic. The surreal experimentation of the instrumental track transitions into a clearly delivered, straightforward lyrical message: An anonymous vocalist, in a whisper, pleads for peace. The vocal delivery, soft and soothing, is completely at odds with the dissonant background music. Desperation has never sounded more thrilling.

Einstürzende Neubauten, “Steh auf Berlin” (1981)

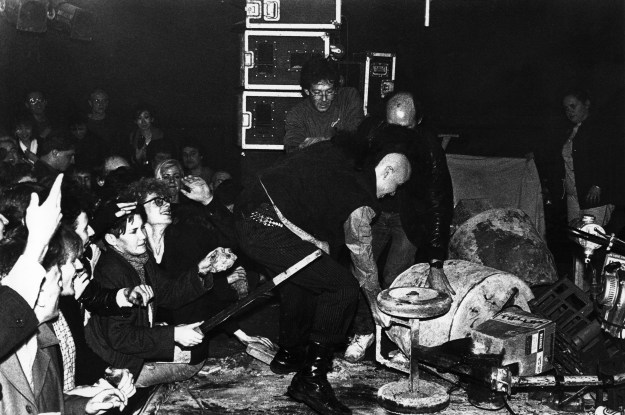

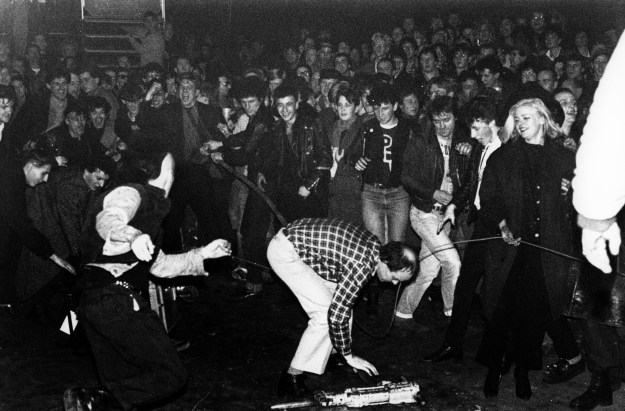

West Berlin’s Einstürzende Neubauten (Collapsing New Buildings) declared war on musical convention with its 1981 debut album, Kollaps. Perhaps more than any other band in the city at the time, it embodied Berlin’s hedonistic chaos.

The idea of the band, led by the eccentric Blixa Bargeld, was crafted the day he received a chance invitation to play at Prenzlauer Berg’s Moon Club. The club promoter had no idea what he had signed up for; clad in black, the musicians who played alongside Bargeld were just friends who happened to have free time that night. They were like New York’s nonconformist No Wave scene but even more devoted to an I-don’t-give-a-f*** DIY ethos. Einstürzende Neubauten, which has never had any desire to break into the mainstream, made even the heaviest, most intense metal bands look and sound tame.

This song, whose title translates to both “Stand on Top of Berlin” and “Wake Up, Berlin,” is a perfect four-minute summation of the uncompromising group’s explosive, deeply unsettling energy. The track is introduced by the metallic buzzing of power tools, a choice as rooted in not being able to afford real instruments as it was in wanting to create the most cacophonous, extreme music imaginable. A clanking, unrelenting pulse lasts throughout, and there is no discernable sense of melody. The instrumental section, if not for its brilliant drum pattern, sounds as if it could have been sourced from random factory recordings. Bargeld’s vocal performance, along with lyrics that speak of illness, decay, noise, and smoke, would befit an apocalypse. The album, though shunned at first, laid the abrasive foundation for what would eventually be called industrial music. Artists committed to reaching the point where avant-weirdness meets rock and roll still, for good reason, reference this challenging record for inspiration.